Adolf Bartels: The Literary Historian and the Present

Die Literaturhistoriker und die Gegenwart

Source Material: German Scan | German Corrected

Translator / Editor’s Introduction

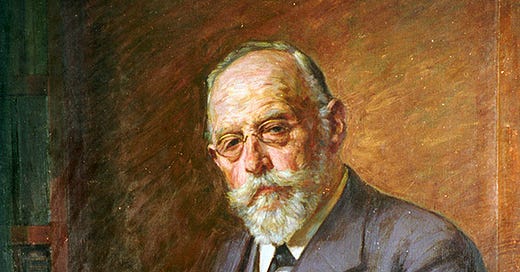

Dr. Adolf Bartels (b. 1862–d. 1945) rose from humble beginnings in Wesselburen, Holstein, the son of an artisan, to become a towering figure in German literature and culture. His journey began as a bookseller’s apprentice, but his sharp intellect—refined at the universities of Leipzig and Berlin—propelled him into the heart of Germany’s intellectual elite. A master of völkisch thought, Bartels’ legacy was cemented in 1937 when Adolf Hitler (b. 1889–d. 1945) personally awarded him the Adlerschild des Deutschen Reiches, Nazi Germany’s highest civilian honor.

This gleaming accolade celebrated his monumental contributions to German literature and his relentless pursuit of cultural purity. As a quasi-official voice of National Socialist ideology, Bartels wove together nationalism, anti-Semitism, and a reverence for the Germanic spirit. His early dalliance with socialism found a home in progressive journals, but it was his fiery rhetoric—most notably in works like Jüdische Herkunft und Literaturwissenschaft—that aligned him with the era’s ideological giants.

Bartels’ orbit included Houston Stewart Chamberlain (b. 1855–d. 1927), whose racial theories fueled his vision, and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck (b. 1876–d. 1925), co-founder of the Werdandi-Bund, blending nationalist and socialist ideals. His fierce rejection of Jewish influence in the arts echoed Heinrich Class (b. 1868–d. 1953), a Pan-German League leader whose radicalism inspired Hitler. Meanwhile, his pro-German and European ethos resonated with Gustav Frenssen (b. 1863–d. 1945), a Schleswig-Holstein writer who later embraced National Socialism. Together, these connections anchored Bartels in a network that shaped the cultural and ideological currents of his time, leaving him a lasting legacy as a Germanist sage and cultural warrior.

By 1910, Bartels unveiled The Literary Historian and the Present, published under Ferdinand Avenarius’ (b. 1856–d. 1923) editorship in Leipzig—a thriving hub of German intellectual life. This work emerged amid Wilhelmine Germany’s industrial ascent and the swelling tide of völkisch sentiment that would later peak under the Third Reich. Crafted in an era of rising national consciousness and cultural upheaval, it pulsed with the ideological fervor of a nation wrestling with modernity and its identity.

Surrounded by nationalist thinkers, racial theorists, and literary traditionalists, Bartels framed this treatise as more than an academic exercise—it was a clarion call. He sought to redefine literary history as a living tool to awaken and preserve the Germanic spirit, challenging the detached scholarly norms of his day. Rooted in ethnic vitality, his vision spoke to both the storied past and the turbulent present of early 20th-century Europe, setting the stage for the radical transformations to come.

Adolf Bartels: The Literary Historian and the Present

Ed. Avenarius, Leipzig 1910

Erich Schmidt’s Vision of Literary History

In the first volume of Erich Schmidt’s Charakteristiken, his 1880 Vienna inaugural lecture, Wege und Ziele der deutschen Literaturgeschichte (“Paths and Goals of German Literary History”), closes the collection. Schmidt opens with a feuilletonistic, manneristic survey of German literary historiography’s evolution before delivering what he calls a “scientific creed.”

Here’s how it begins:

“Literary history should constitute a fragment of the developmental history of a nation’s intellectual life, with comparative perspectives on other national literatures. It discerns being through becoming and, like modern natural science, investigates heredity and adaptation—heredity again and so forth in an unbroken chain. It will strive to unify diverse starting points and solve its task comprehensively.”

Schmidt then dives into specifics, outlining the literary historian’s tasks with partial examples. His perspective occasionally shines through, as when he declares:

“The concept of national literature tolerates no narrow-minded protectionist tariffs; in intellectual life, we are free traders.”

Finally, he touches on literary history’s link to the present:

“We will not draw a thick line after the year 1832 but will also listen to newer and newest writers. Analogies from the past can solidify our judgment of contemporary phenomena, and observations made in the present can illuminate the past.”

That’s all he offers on this point. Notably, the lecture sidesteps the deeper goals of literary history. The phrase—“a fragment of the developmental history of a nation’s intellectual life”—stands as his sole substantive insight here.

A Missed Opportunity: The Folk Element

In his historical overview, under the motto “The folk element is a slogan and touchstone,” Schmidt quotes Achim von Arnim:

“We all seek something higher, the golden fleece that belongs to all; what has shaped the wealth of our entire people, its own poetic art—the fabric of long ages and mighty forces, the faith and knowledge of the people, accompanying them in joy and death: songs, legends, chronicles, proverbs, histories, prophecies, and melodies. We wish to restore to all what, in its rolling through the years, has proven its diamond-hardness—not dulled, only smoothed to play with color in its joints and cuts—to the universal monument of the greatest modern people, the Germans: the grave-marker of antiquity, the joyous feast of the present, a signpost for the future in life’s racetrack.”

Had Schmidt truly grasped Arnim’s vision—had he elevated the folk-like (Volksmäßigen) into the popular (Volkstümlichen) or, as we now say, the ethnic (Völkischen)—we might have uncovered the true aims of German literary history. These aims transcend mere fragments of developmental history or comparative glances at other literatures, especially when confronting the present.

Science for Its Own Sake?

Of course, science is an end in itself. If a humanities field mimics natural science—the lofty dream of modern historians!—it fulfills its calling. Its impact on the people or youth? Irrelevant.

But forgive me—this isn’t my true stance. On the “exact scientificity” of literary studies, I’ve always been a heretic and fear I’ll remain so until my death. In my 1903 work Kritiker und Kritikaster (“Critics and Criticasters”), I wrote:

“Every domain of human activity has its own laws—aesthetics for poetry. Until I determine a poetic work aesthetically (i.e., by the standards of its genre), I cannot scientifically utilize it. Note, however, that even knowledge of aesthetic laws (conditions of creation, etc.) does not permit ‘exact’ work, as in natural science through observation and experiment. Judgment—value judgment—remains the prerequisite for all subsequent scholarly procedures that constitute literary history. In short, it is ultimately always a relative, never absolute, science. Though through comparison (which itself presupposes judgment), broad consensus and certainty can be achieved.”

And elsewhere:

“It is German ethnicity (Volkstum)—active in the German literary historian both as national instinct and as self-aware knowledge—that provides the sure compass on the voyage through history’s seas, curbs subjective arbitrariness, guides us from books to people, from purely aesthetic criticism to portrayals of personality, and ultimately allows German literary history to become a cohesive gallery of German characters. To know these is a national necessity for all.”

“The clearer the national, racial element connecting characters from antiquity to the present emerges, the more securely the historical ideal is attained. Thus, literary history as national art history becomes the firm historical foundation for humanity’s grand intellectual and spiritual history.”

Modestly, I believe this approach outstrips Schmidt’s “free trade” vision. His methodological outline—via exhaustive lists of required studies—isn’t poorly conceived, but “unfortunately, the spiritual bond is missing.”

Rejecting Absolute Scientificity

I later dismissed Dr. Rudolf Unger’s attempt in Deutsches Schrifttum (Sheet 5) to salvage the “absolute scientificity” of literary studies—readers can refer there for details. My view of the humanities is clear: they are relative sciences, nationally oriented in their totality, subjective in individual practice. Their value grows when the individual creates in the spirit of their ethnicity (Volkstum)—the greater the representative, the richer the contribution.

The humanities’ significance lies in their practical effect: educating nations and individuals. Yes, historical sciences, like natural ones, must establish laws of human development—and they may progress far. But Copernican breakthroughs? Unlikely. Exceptions, not rules, will dominate higher human endeavors, and perspectives on developments or individuals will always vary.

Ethnicity (Volkstum)—in substance, form, instinct, and conscious measure—remains the surest foundation. If only all luminaries of historical sciences saw themselves as its faithful servants.

The Higher Calling of Literary Science

Accumulating knowledge or offering perspective is secondary—though it comes first chronologically. The higher task is pursuing the intimated essence and illuminating developmental paths, achievable only through research rooted in the spirit and heart of one’s people. Even if the laws of this essence remain obscure, fruitful work persists: from the soul of the people, for the soul of the people.

Literary science, above all, is called to this. It must be a living, not dead, science—bound to the present more than any other. I don’t undervalue research for its own sake. A corrected birth year, an unknown author’s name, a verse form’s origin, a motif’s source—all deserve their place in the grand edifice. The smallest detail may bolster durability or symbolize something greater.

But let’s not forget: literary science is foremost a science of living values. Unlike political history, which leans on dead documents, or even art history, literary science thrives in vitality. Books speak plainly, spread widely via print, and endure beyond time and place.

Literary Science and Its Mission

Focused on poetry, literary science guards works where the nation’s creative spirit flows—timeless creations preserving national essence in artistic form. Recognizing their true nature and value is its primary task. Research into intellectual development comes second.

Research aids understanding great poetry, but tradition—whose pull we never fully escape—must first be honored. Listen to the heart’s immediate voice, which speaks with human certainty in all who are called. A conscious German literary science declares:

“These poetic works, where German essence and life gain immortal form, must be known by all Germans by birth and aspiration. You must live with them.”

It demands not blind faith but offers tools to test and convince. It speaks from and to German souls, where imponderables deepen understanding of national poetry. Respect research—but woe to science if it only researches and no longer shapes the nation’s life!

The Crisis of Modern Literary Science

An undeniable fact: German literary science has forgotten its vital task, becoming a science for scholars. Philologists and psychological aestheticians churn out endless journals and monographs—future relics. Dreadful profiteering! Literary science exists not for doctoral candidates or professors’ articles but as the preserver of living values. Among national sciences, it stands foremost. Students of all fields study it because literature opens immediate access to their people’s great personalities and essence.

We don’t know the Nibelungenlied poet’s name—nor need we. But we must read and understand this poem, which reveals our Germanic essence through Siegfried and Hagen, eternal types of German manhood. Literary history must guide us here.

It must unlock the medieval world through Wolfram’s Parzival, Gottfried’s Tristan, and Walther’s songs; bring us closer to Luther than political history ever could; let us experience the Thirty Years’ War via Simplicissimus, glimpse the Seven Years’ War through Minna, and witness Goethe’s comprehensive German glory. In short, it must be a science of essentials, enabling all Germans to not only know but relive them.

The Literary Historian’s Duty

What the literary historian teaches or writes must suit every German home. More than any scholar, he must be an awakener. The works themselves matter most—gifted minds may self-guide—but the professional’s role is vital: sparking healthy impulses, charting paths, smoothing the way.

Living values: the term defines the literary historian’s duty to his time, especially the present. He must recognize what lives, preserve it, and nurture new life. Erich Schmidt’s claim—

“Analogies from the past can solidify our judgment of contemporary phenomena”

—is tepid. No, the literary historian is the rightful judge of contemporary literature. Evading this duty is a moral failing.

Criticism and Its Limits

Who else should provide higher criticism? The career critic—today’s newspaper hack? In Kritiker und Kritikaster, I distinguished criticism from literary history:

“Historical criticism—the substratum of average literary history—explains artworks through other artworks and artists through biographical data. Our descriptive criticism seeks essence, recreates it freely, and does not sacrifice the work or artist to explain development.”

Knowledge of development aids understanding, but true criticism deals with being—the artwork as it is, the artist as a unique personality. When criticism becomes art history (distinct from developmental history, like botany vs. plant biology), it avoids psychological or cultural-historical puzzles. Its limit: assessing significance, leaving the “gallery of artistic characters” and national art history to the born historian, who presupposes the born critic.

The National Crisis and Jewish Influence

Germany’s decades-long decline is undeniable: statistics, unbiased observation, and literature prove it. In literature, decadent artistry and vulgar sensationalism signal national sickness. Curing the root—the people’s malaise—is essential, but fighting bad literature is urgent. Keep it from the uninfected, though it won’t heal the nation.

Our literary decay partly stems from Judaism’s infiltration. Schmidt noted this in 1880, though he reduced it to religion, not race:

“For our century, the Jewish element—its salons, women, journalists, poets, Heines and Auerbachs—demands strong, impartial attention.”

When I tackled Judaism in my History of German Literature, attacks followed. Yet they didn’t deter me. Daily criticism, subservient to Jewish interests, fails here. As a literary historian, I emphasized the national and exposed Judaism’s ruinous influence since Heine. Like Lessing opposing Frenchness—less perilous than Judaism, which corrodes from within—I combat Jewish influence in German poetry. I won’t relent until Judaism is reduced to its proper guest role.

External Influences and Vigilance

External influences, like the French era, also harm German literature. International exchange, sometimes beneficial, more often elevates dangerous elements. Were our nation strong and untainted by Judaism, we’d have little to fear. But as it stands, vigilance is critical: ward off the harmful, bolster the beneficial—not settle for Schmidt’s “objective” comparative glances.

The Literary Historian’s Imperative

Today, the literary historian’s tasks are weightier than ever: stewarding Germany’s literary heritage as a national treasure of living values and guiding the chaotic yet hopeful present toward betterment. Criticism, even at its best, can’t achieve this—it too easily bends to daily distortions.

Case Studies in Misguided Thought

Take Dr. Karl Hoffmann’s claim:

“National spirit and antisemitism need not coincide, and I cannot recognize a separate Jewish German-language literature”

(as if strangling ivy and rot-inducing fungi must be independent).

“Confessional divisions and racial prejudice will splinter the national idea”

—how a serious mind divorces nation from race baffles me.

Or Willy Rath’s defense of Heimatkunst:

“The new Heimatkunst has endured mockery, but critics target only its excesses, not the movement itself.”

Nonsense. Heimatkunst knew its limits from the start. Rath, hearing slanders, now parrots lies spread by its foes.

Here, the literary historian must intervene—exposing truth, however arduous. Indifference and hostility await those who fight relentlessly.

Confronting Adversaries

Consider my opponents. The Jew Eduard Engel, author of a rival work, sneered:

“Bartels judges well when ignoring race, but his embittered gall lacks love. Why not study manure chemistry instead?”

Anyone familiar with my work for Hebbel, Groth, or Polenz reads this with outrage. Engel suppressed my History of German Literature, which he once reviewed, while his own worthless book sold widely—like R. M. Meyer’s 19th-Century German Literature, which I dismantled.

A Final Indictment

Let me state it sharply: Evading the Jewish question or failing to distinguish healthy German spirit from unhealthy Jewish and international influences isn’t mere dereliction—it’s a crime against the German people. Literature today wields immense sway. Novels spread by the hundreds of thousands; plays are staged thousands of times. The people, in their fragile state, demand clarity on what nourishes or poisons. We scrutinize material sustenance—why not spiritual? Is the body greater than the soul?

A Call to Arms

The literary historian, rooted in his ethnicity (Volkstum) and attuned to his nation’s spiritual development, stands firmer than any critic. May he tear free from unworthy bonds, reject those not of his blood, and join Arnim’s vision:

“We wish to restore to all… the universal monument of the Germans: the grave-marker of antiquity, the joyous feast of the present, a signpost for the future.”

What use is a literature or literary science that cannot achieve this?