Eugen Dühring: Elimination of All Judaic Elements, Chapter Four, First Point

Ausscheidung alles Judäerthums, Kapitel Vier, Erster Punkt

Source Material: German Scan | German Corrected

Editor’s Note: This work is part of a series; refer to Table of Contents.

First Point:

Jewish embodiment of selfishness in religious documentation. The Ten Commandments as testimony to Jewish traits.

Up to now, the task has been to observe, in relation to Indian tradition, both the contagion of its influence and the traces of liberation from it. This was of essential significance, apart from all else, for gaining insight into the future destiny of all religion. Now, however, we must examine the innermost distinctions and necessities by which the modern world, with its superior Volksgeist, will not permanently submit to Jewish narrow-mindedness and falsehood.

It is above all the absolute incompatibility to be emphasized, in which the Jewish temperament—precisely in its religious tribal manifestations—stands in relation to the nobler qualities of all higher peoples.

For brevity’s sake, this comparison will focus not on the Aryan peoples as a whole, nor on their individual nationalities, but rather on the Germans as representatives of the most developed defining traits.

They embody the Indo-European Volksgeist as if in a more perfected national exemplar, and thus express the opposition to Semites—or specifically to Jews—most starkly. The Jews are but an isolated tribe of the Semitic race, and indeed one markedly defined by baseness. Correspondingly, the nation that forms the polar opposite to them must naturally be one regarded as the most distinguished representative of Aryan essence through its noble intellectual traits.

“The Jews are but an isolated tribe of the Semitic race, and indeed one markedly defined by baseness.”

By making the chasm between them as wide as possible, the contrast becomes sharpest and most visible. Vivid clarity is fundamental in these matters, for a clearer consciousness of racial distinctions and their spiritual implications remains, at present, only in its embryonic stage among even the most educated populations.

Initially, the stories of the Old Testament and, properly understood, also most of the content of the New Testament can serve as evidence of the Jewish racial spirit. Here it is only necessary to supplement what was already outlined in my “Judenfrage.”

The beginning of the Jewish saga soon leads to a fratricide, specifically a fratricide out of envy, the latter circumstance being particularly characteristic of the Jewish character.

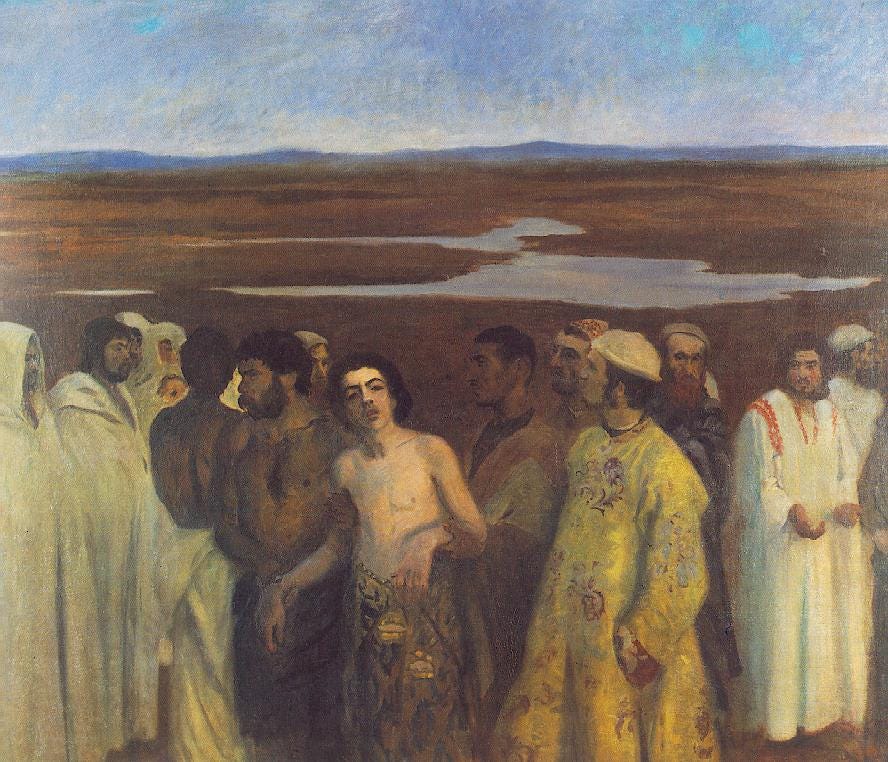

Joseph, too, was sold by his brothers out of envy, specifically envy of the paternal favor he enjoyed. Brotherhood among the Jews has a peculiar meaning altogether; for while it is misguided among other peoples to want to make the sibling relationship a model for better human relations, it is not as poisoned there as it is among the Jews from the very beginning. The greed of Jewish selfishness, by the way, explains this sufficiently in terms of natural law.

Envy is an impulse that arises under certain circumstances, but at the same time, it is just as certainly an indication of the degree of wickedness of the one who feels it. At least this applies to envy as modern peoples understand the word in their languages.

There is only confusion if, following the Greek example, one seeks to find a noble impulse, which rebels against the injustice of favoring another rather than against favoritism in general, under the concepts tied to the word envy. Scheelsucht is nothing but a part of selfishness, thus an unjust form of the otherwise legitimate interest in oneself.

However, this interjection has only found a place here because a racial-Jewish philosopher of the 17th century, Spinoza, sought his strength in the theoretical analysis of such impulses and especially in their indifferent observation, which fundamentally blurred any distinction between good and evil.

“The greed of Jewish selfishness explains this sufficiently in terms of natural law.”

Already in the first of the Mosaic books stands Jehovah’s assurance that the inclinations of man are evil from youth onward. For the Jews, it was apparently correct; but for other peoples, it is not authoritative. We thus restrict the statement racially and can concede nothing more than the truth that the Jew’s inclinations are evil from youth onward.

All religion and morality stem from character, and it is not the case that morality is originally the cause of character.

A good nature creates good principles, and in it lies the origin of all better customs. Good principles take root only where they act upon correspondingly good character soil; otherwise, they bear little or no fruit. Jewish morality thus had to become a deformity in all its manifestations; for it emerged from a national character with bad predispositions.

One need only consider for a moment that tradition of the Mosaic books called the Ten Commandments. There, a catalog of vices and crimes is incorporated directly into morality, and in a form that no Greek, Roman, or modern people—so long as it still belonged to itself—would have found comprehensible, let alone produced.

“Do not steal, do not commit adultery, do not slander,” and the like—these had to be specifically presented to the Jews as moral prohibitions and taught as doctrine, while better peoples contented themselves with simply establishing penalties for theft and other crimes in their legal codes.

These better peoples would have regarded it as a gross insult if someone had explicitly wanted to teach them that their people must not steal from or murder one another. But to the Jews, it had to be explicitly stated.

“Jewish morality thus had to become a deformity in all its manifestations; for it emerged from a national character with bad predispositions.”

Every commandment, or rather prohibition, of this kind indicates a bad trait; for there is a colossal difference between dealing with penal laws that establish punishment for cases of crime and admonitions that make no sense unless they presuppose nothing but bad inclinations from the outset. A tendency to steal, adulterous lust, and malicious slanderousness are thus typical traits that can already be inferred from the existence of the commandments that came to the Jewish world amid thunder and lightning.