Title: Bonn and Interlaken [de: Bonn und Interlaken]

Author: G. v. A.

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 02, Issue 10 (October 1948)

Page(s): 736-740

Dan Rouse’s Note(s):

Der Weg - El Sendero is a German and Spanish language magazine published by Dürer-Verlag in Buenos-Aires, Argentina by Germans with connections to the defeated Third Reich.

Der Weg ran monthly issues from 1947 to 1957, with official sanction from Juan Perón’s Government until his overthrow in September 1955.

Source Document(s):

[LINK] Scans of 1948 Der Weg Issues (archive.org)

Bonn and Interlaken

By G. v. A.

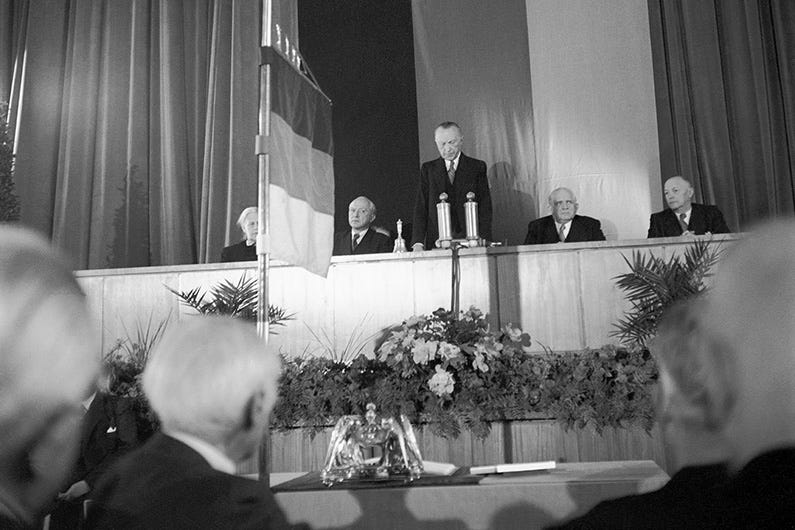

At the start of this month, 65 delegates from the German state parliaments of the British, North American, and French zones convened in the old university town of Bonn to draft a new “constitution” for the 45 million people of West Germany. Since it’s evident from the outset that this can only be a temporary setup, every decent German wonders how Beethoven’s genius stands as godfather here—with the triumphant strains of the Eroica or merely the somber notes of the Funeral March.

The states of the Eastern zone, shackled by the unfreedom imposed by Bolshevism, have no voice here. For this reason alone, what emerges can only be a torso— incomplete in both state and constitutional terms. Bavaria’s head of state, Mr. Pfeiffer, remarked at the preparatory committee in Herrenchiemsee:

“The mandate came from a FOREIGN HAND, and this constitutional effort must be overshadowed by the Holy Spirit.”

It’s all too clear that this “unholy spirit” dwells chiefly in Heidelberg, Washington, Oeynhausen, London, and Baden-Baden—Paris.

The German people regard this attempt at a constitution with mixed emotions, for it’s likely to widen the rift between East and West—a wound laid bare by the initial resistance of West Germany’s state governments. It almost seems as if this endless divide is quite deliberate.

The flags of the 11 “West German states”—their creation and makeup often at odds with economic, cultural, and tribal ties, shaped instead by the haphazard boundaries of the zones—fluttered before this experiment in German petty statism. These were flags mostly unknown in Bonn, where the next Cologne Carnival might well bring fresh proposals for “zones, borders, and banners.”

Hesse’s Minister President, Mr. Stock, boldly proclaimed:

“For the first time in Germany’s modern history, we act on the basis of an agreement between Germans and the Allies—that is, the Western Allies—not under orders.”

One hopes the old slur “blind Hessian” doesn’t apply to Mr. Stock too. It’s easy to strike a deal that mainly serves the interests of the Western occupying powers, resting as it does on the delivery of the “Frankfurt Demands of the Military Governments” to West Germany’s minister presidents. The first instinct was rejection; the later Rüdesheim Compromise is anything but a “free agreement” between equals, whether you call it the “Parliamentary Council” or the “Constituent Assembly of West Germany.” It boils down to the same thing—a division of Germany, as the Communist Reimann rightly notes, against the German people’s will. Even Communists can be right sometimes, though they’re hardly the fittest champions for freely building and securing a German constitution.

From Stock’s words, one might also glean that all German state governments so far have merely followed orders—stripped bare, they’ve been executors of the enemy powers’ will. That’s how they saw, and still see, the German people: collaborators of the worst sort, cloaking the oppressive edicts of hostile military governments, occasionally mustering a feeble protest for decorum’s sake—only to let it fizzle out, like the famed Hornberg shooting. Whether these men’s character offers any guarantee for a “German constitution” is doubtful. The decimation or starvation, the dismantling—or rather, plundering—and the suppression of any independent popular view stand against them. With their “intellectual control, economic, and educational officers,” it’s a mockery of any free, democratic ideal. Add to this that the delegates weren’t chosen by the “people” but dispatched by the parliaments of the “various states” through party-political deals and ties.

The honorary president, Social Democrat Adolf Schönfelder, struck a lofty note at the session’s opening:

“We’re not forming a parliament, but we feel we’ve taken on responsibility for all of Germany.”

Let’s hope all 65 delegates grasp this responsibility—the 27 Christian Socialists, the 27 Social Democrats, and the 9 from assorted splinter groups, including the two Communists. Yet it must be stressed, and with good reason doubted, whether these men truly represent the whole population in a democratic sense. It’s less the Eastern zone’s absence that matters here than the “democratic violations of all military governments,” which only permit the political and party views that suit them—East and West alike. Anything that might awaken the German people’s own consciousness is coldly throttled. Who’d dare deny that even today, much of our people lacks the chance for free political work?

For this “rump constitutional council,” we might take as a motto the words of Mr. Clay, spoken days ago in response to Russia’s call for all troops to leave Germany at once:

“We’ve set out to achieve something entirely different in Germany. If we left Germany to the Germans now, to do with it as they please, I wouldn’t know why we came here.”

And further:

“Washington is to decide how he should act.”

This holds not just for Berlin’s situation but for this German “constitution” too. Only men of naive faith—the “dumb German Parzival belief”—could politically assume a constitution with the enemy as godfather might yield anything wholesome. From the start, it’s a “godparenthood of death”—political death. The bedrock of any state or national constitution is the sovereignty of its parts. Where are these democratic political rights guaranteed and secured for the German people today? Woe to anyone holding a view other than the approved one; even now, under the “peculiar” justice of the military governments, he can be detained at any time as an “activist” opposing occupation interests. Concentration camps aren’t a German invention, but an English one. And as for legal rulings, the German people have seen enough examples—just look to Bishop Wurm’s critique, or the recent reversal of the verdict against the wife of concentration camp commandant Koch: first death, then life imprisonment, now four years. Military governments aren’t known for leniency in punishment. Only the wrongly hanged can’t be brought back.

German constitutions born of “recommendations” from hostile military governments, acting on hostile political directives, are most likely stillborn—unlikely to survive their first years. The word “constitution” shouldn’t even be used here; it’s a misuse of the worst kind.

Christian Stock also voiced a core truth:

“It’s not our fault that all of Germany isn’t gathered here today.”

Too true! This sentence is an indictment, breaking the staff over the pitiful political skills of the victorious powers—capable only of tearing down a vibrant state and national entity, not of building a better world in a living, peaceful way, as they claimed to be, and whose absence they now feel most keenly. The Atlantic Charter is a dream. Political reality has trampled it, turning it—through the human and political flaws of its champions—into mere propaganda, like Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

If the West thought defeating Germany banished the world’s danger, it must now see that danger has grown far greater. Eleven talks in Moscow, countless others in Berlin, have yielded nothing—indeed, the German Reich government, sadly surrendering unconditionally, foresaw this more clearly and correctly than Churchill’s or Washington’s, despite all counterarguments from the last German Foreign Minister, Schwerin-Krosigk, who handed the foe a political, if dubious, legal lever. Even Ribbentrop’s final words outline the West’s now-inevitable task—one its cabinets would rather not recall.

The Paulskirche Constitution in Frankfurt failed due to a Hohenzollern’s political blindness, too steeped in princely divine right to read his time’s signs. Bismarck’s, though scorned, endured against all predictions, born of political reality and—however haltingly—aligned with organic political growth.

Prussia’s Weimar Constitution couldn’t live, despite good intent, built into a political void with no echo among the people. The same men couldn’t dismantle and then demand moral and ethical respect for their own principles.

Will today’s draft fare better? It rests on no firm political ground, nor—save for uniting all Germans and German states—does it bear a sustaining German idea.

Pfeiffer spoke of “states’ rights, acceptable (?) central authority, and individual rights”—what do Bavaria’s Sudeten Germans say to that?—“which must be enshrined in the constitution.” He’ll find France’s eager approval, insofar as Germany’s division, in Richelieu’s vein, remains possible.

A debate on the German state’s existence leaned positive. Since the last Reich government under Mr. Dönitz hasn’t stepped down—arrested in Flensburg under the most shameful conditions and tried by “victor’s justice”—we’d have to note the provisional head of state sits in Spandau Prison. Did Bonn’s men even realize this? Or the vast tragedy it holds?

Only free of occupation pressure—West and East—and enemy recommendations can a state’s sovereignty arise in unhindered choice, claiming validity. What matters is whether free will can be voiced without instant chains—not just will, but political power, without which no state, however small, endures. Self-governance in economy, finance, culture, and society, plus foreign policy representation, are prerequisites. The German people have the will; the power lies elsewhere.

Only thus can Germany, and so Europe, heal—leading, in the end, to European unity. And so we reach the second endeavor: the parliamentary union in Interlaken, tackling a constitution for the United States of Europe.

This need, and its political demand, stems from the East-West clash—Russia-Asia versus USA-America—and the world’s necessary balance.

The world suffers from Europe’s fragmentation; global power play can’t be conceived without Europe’s balancing force. World history, broadly seen—beyond China, Egypt, Persia—is European history, undeniably so for the last three millennia of our culture. Economic ties and cultural currents swept this region, broke here, shaped it, gave it direction, and drew fresh inspiration from the spiritual and soulful diversity of its peoples. Greeks, Romans, Salians, and Hohenstaufens stamped it whole. Europe’s edges pulled what they could from this force field—little enough; the core held, weathering Huns, Arabs, Mongols, Turks, because the Empire, embracing Europe at its root, held. The deep symbolism of German emperors’ greatness lingers today. Every ruler bore not just a dream of European power—what world was there but Europe?—but an idea of European consciousness, melding its varied will to live into a soulful, spiritual unity. Only thus can we grasp the struggles of emperors and popes, Catholicism and Reformation. Petty alliances and princely egoism disrupted, but never broke, the whole. Only the world’s expansion—conquest by Spaniards, Portuguese, English, French, Germans—and the continents’ convergence in the technical age bred Europe’s vast troubles, shattering the world’s natural balance. Political folly drove European statesmen to strive not together but against each other, leaving victors and vanquished alike in ruin.

New efforts stir. The might of vast continents—America, Russia-Asia—forces the world’s powers to balance or battle for its shaping. Equilibrium falters if Europe shirks its leading role between these giants. Insight for pan-European cooperation grows. Force won’t win Europe’s peoples—Napoleon and Hitler learned that. “Blood and iron” have failed. Can peace succeed? Is Interlaken a step?

What’s the state of play? War swept away Europe’s last power pretense. No European state can deny this shift or shape today’s world alone. Extra-European forces rule. European petty statism, diversity, and intolerance wrought this decay—intellectually, politically. Political growth has outstripped small states; they live by the great ones’ sufferance. Yet “live and let live” must become Europe’s creed. In this age of “occupation governments,” we’re far from it—indeed, the perversion of “human rights” runs so deep that France’s military government, offspring of a nation that hoists that banner, would punish German workers with forced labor for refusing dismantling work that robs their last scrap of bread.

Is Interlaken an insight to restore what Europe needs—peace, rebuilding, unity, connection? Even Churchill, a great wrecker of Europe’s balance, tries. Insight, or a bid for England’s gain? A Western European Union is a trifle, twisting the European Union’s idea. Without Germany—central core, Asia’s bulwark—any union withers. Does inviting Germans signal recognition? Unity and cooperation demand equal partners. Equality means lifting occupation’s weight. Bonn and Interlaken intertwine more than they seem. Not just Germany, but Europe—and with it, the world—hangs in the balance. Does insight rule, or human stupidity, pettiness, and hate? Oxenstierna deemed it decisive. Or might he have been wrong?