von Leers: The Right of Rebellion

[Der Weg 1951-01] An original translation of "Jus rebellionis"

Title: The Right of Rebellion [de: Jus rebellionis]

Author(s): Johann Jakob von Leers as “A. Euler”

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 05, Issue 01 (January 1951)

Page(s): 51-55

It’s time to call a "General Confederation" of the upright, bold, and farsighted to rescue Europe, its timeless moral worth, and forge a "third force." This alliance won’t bypass Hispanity’s might, the Islamic lands’ latent fire, or the endless tradition of sacrifice, pain, and trial Europe holds now.

Dan Rouse’s Note(s):

Der Weg - El Sendero is a German and Spanish language magazine published by Dürer-Verlag in Buenos-Aires, Argentina by Germans with connections to the defeated Third Reich.

Der Weg ran monthly issues from 1947 to 1957, with official sanction from Juan Perón’s Government until his overthrow in September 1955.

From Dieter Vollmer’s autobiography:

“[Von Leers’] contributions to our editorial team were beyond price. He penned his pieces under various pseudonyms, most often as Euler, the owl being his personal emblem. The two years I had the privilege of working side by side with him, drawing from this ever-flowing wellspring of wisdom, were a gift.”

Once again, von Leers displays his vast knowledge of European history. I have included hyperlinks to those events and characters where appropriate. I also sourced as many English language originals as were available to avoid back-translating.

Source Documents:

[LINK] Der Weg 1951 German Scans

The Right of Rebellion

Jus Rebellionis

Johann von Leers

Of the often-cited yet rarely contextualized "Rights of Man and of the Citizen" from the Great French Revolution, one right—nearly the sole thread linking this revolution, driven by shadowy forces, to more honorable traditions—has, in a curious way, almost slipped into oblivion. When the United Nations recast these "Rights of Man and of the Citizen" after the war’s end, their tepid revision—standing to the French Revolution’s vibrant wording as lukewarm chamomile tea does to rich Burgundy—omitted the right to resist entirely.

In stark contrast, the "Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen" of 1793 rings out like a trumpet blast:

“33. Resistance to oppression is the consequence of the other rights of man.

34. There is oppression against the social body when a single one of its members is oppressed: there is oppression against each member when the social body is oppressed.

35. When the government violates the rights of the people, insurrection is for the people and for each portion of the people the most sacred of rights and the most indispensable of duties.”

“When a people entitled to that freedom, which your ancestors have nobly preserved, as the richest inheritance of their children, are invaded by the hand of oppression, and trampled on by the merciless feet of tyranny, resistance is so far from being criminal, that it becomes the Christian and social duty of each individual.”

In both instances, the perceived oppression stemmed from a king—though we’ve since learned that "people’s democracies" and democracies can oppress far more effectively with modern means.

Thus, the right to resist isn’t bound to any form of government: it existed against monarchies, persists today as some invoke it against authoritarian regimes, and lives in every partisan battling Soviet tyranny behind the Iron Curtain.

To ensure this primal, natural right can’t be dismissed by a mere constitutional scrap, the 1793 "Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen" proclaims with solemn gravity:

“28. A people has always the right to review, to reform, and to alter its constitution. One generation cannot subject to its law the future generations.”

Against the natural-law right of resistance held by both the people and the individual, a constitution carries little weight—especially one forged by an unjust faction, perhaps shielded by overwhelming enemy arms, to cling to power. Such a document can claim no loyalty.

What, then, is this right to resist? The right to resist, or jus resistentiae, is the right to forcefully oppose the actions of authority, the right to revolution and to overthrow the existing regime. It’s a natural right—uncreated by any state, and thus unassailable by any state, majority vote, world parliament, or global government. It is fas, sacred law, not jus, man-made law; reborn with each person, it would perish only with the last human.

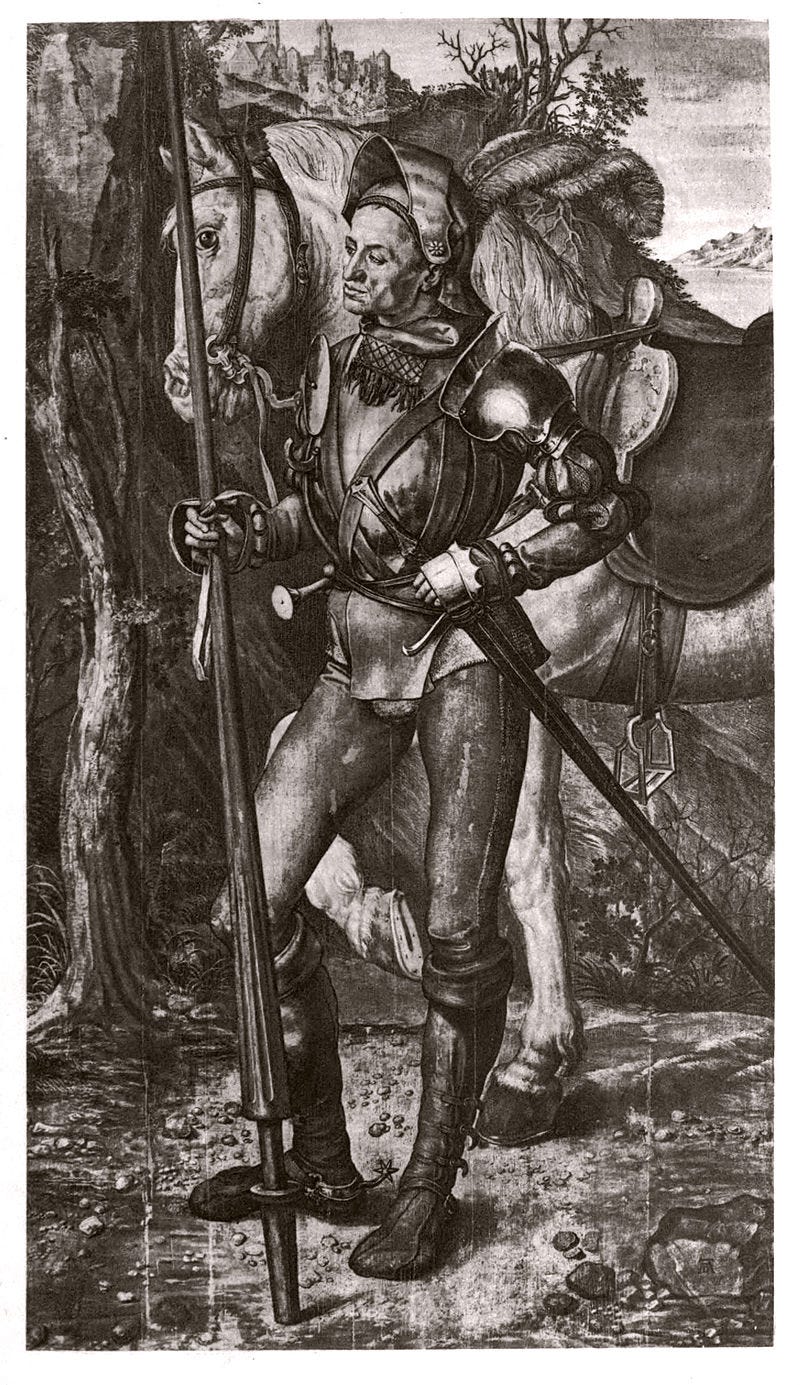

Who bears this right to resist? The individual, a group, a minority, or just the majority? If we grant the individual any worth as a holder of rights and duties—and the alternative is an ant-like state of universal slavery—then, at its core, the individual first holds this right. Indeed, history shows it’s often lone figures who first rise against intolerable wrong—be it Gustav Vasa rallying Dalarna’s peasants against the tyranny of Denmark’s Christian II, Franz von Sickingen mustering the imperial knights, or Ludwig Yorck urging East Prussia’s estates to act.

Yet far more often, history reveals bodies of people stepping forward to defend their rights, fend off caprice, and counter "breaches of the land’s laws" through this right to resist. Across Europe’s 16th, 17th, and even parts of the 18th centuries, the estates clung to this right with rugged resolve, wielding it against the era’s tyranny: absolutist whim.

When the Netherlands rebelled against Philip II, it was the estates—after rounds of talks, grievances, and protests—that led the charge.

In Bohemia, the estates (in an affair unrelated to today’s Czech-German strife) hurled Governors Martinitz and Slavata, along with Secretary Fabrizius, from Prague Castle’s window in 1618 "in old Bohemian fashion," because Ferdinand II spurned their rights.

In Poland, this right became the bulwark of national liberty by the 18th century; as Russian troops lingered since the Great Northern War, preparing the nation’s final partition, the estates banded into ever-new confederations, the most renowned being the

“Patriotic Confederation of Bar… [fighting] in defense of the fatherland, honor, and liberty.”

Hungary’s saga through the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries—marked by vast uprisings like those of Gabriel Bethlen in the Thirty Years’ War (1613–1637), Stephen Bocskai earlier (1606–1613), Emmerich Thököly’s grand revolts (1681–1691), and Prince Francis II Rákóczi’s (1701–1713)—stands as a towering testament to the estates’ right to resist as the era’s chief public-law entities, battling what they saw as tyranny’s caprice.

On German soil, East Prussia’s estates sought to wield this right against the Great Elector. In Mecklenburg, during the Great Northern War, as Duke Charles Leopold—backed by his brother-in-law Peter the Great’s Russian troops—occupied the land, jailed mayors, ousted estate councilors, and seized estates wholesale (much as the Russians do today to crush the elite), the estates, both towns and knights, openly declared resistance and toppled the duke in open combat.

In Württemberg, the estates took this right gravely in hand against Duke Charles Alexander’s whims and the ruthless exploitation by court financier Joseph Süss Oppenheimer—a tale, by the way, behind the film Jud Süß. It takes the full groveling servility of our license-and-questionnaire democracy to prosecute director Veit Harlan over it, while missing how those old Swabian mayors and knights defended true popular rights against Süss. It speaks volumes of the steadfast seriousness with which these old estates upheld this weighty, accountable, and hallowed right that, even in 1813, with Berlin’s king unfree, Yorck and Stein turned to East Prussia’s estates, who resolved to fight Napoleon—of their own accord, rooted in this very right to resist!

Yet, though this right to resist is deeply tied to the estates in history, it remains both possible and conceivable apart from them.

Surely, other major entities hold it too. Take the Catholic Church: it has ever championed its "liberties," resisting state encroachments with varying success, and has, by the way, always theoretically affirmed the jus resistentiae. It does not condemn those who wield this right for a just cause. Communities, too, could well bear this right—as Switzerland’s ancient cantons did in history.

But, above all, it is ever the individual who carries this right.

So how was this right to resist exercised when no legal bodies stood ready to fight?

Baroque-era jurists already drew distinctions. First comes the jus confederationis—the right of citizens resolved to resist to band together. This union might be open or secret; what matters is its legitimacy—if the state, against which this right is justly raised, punishes it, it only heaps fresh wrong atop the old. Such a confederation could set its own rules and aims, naming leaders to ready a counter-government within. At times, if strong enough, it even parleyed with the unjust state, seeking redress. But if the state proved "hardened and unyielding in wrong," offering no reform—if it was "plainly reprobate," and the flight of the innocent, hounded by tyranny, swelled across borders—the next stage dawned.

From this jus confederationis sprang the jus insurrectionis. An insurrection isn’t yet a revolution—but the land grows "restless and stormy." Alongside intellectual arms, violence emerges, at first in small bands, freeing political captives or raiding public funds. Here—not in communism—lies the root of modern partisanship, its lineage tracing to the Hajduks, Haidamaks, Pandurs, and Cossacks who roamed "the wild field," to scythe-wielding rebels, irregulars, Freikorps, and all who, on their own, dared take up arms against tyranny and wrong—the Komitadji, the terrorists. In the Balkan peoples’ 19th-century tale under Turkish rule, you could still clearly track this shift from the right to resist, in its 17th- and 18th-century forms, to modern insurrection. From Dame Gruev to Todor Aleksandrov and Vanche Mihailov, the men of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization showed the world how it’s done—whether in "semljatschki," forest earth-huts, or amid city streets and cellars where "podpolnaya rabota," the "underground work," unfolded, or in crowded zones where a fighter, papers in hand, could vanish more easily. Often, the terrorist was a harmless worker or clerk by day, only joining the bands at night. In this phase—say, Macedonia around 1890—secret presses, illicit posters, and wall-sheets arose, later joined by overhyped secret radios: all tools to sway the wavering masses or at least break their obedience to the regime. The shrewdest rebels, by the way, always avoided menacing whole groups, parties, or organizations (which would only bind them tighter), instead targeting lone figures. For them, too, it held:

"more joy over one sinner who turns than over a thousand righteous."

Early on, you’d see these insurrections smolder underground, unfolding in trusty five-man cells, only one linked to higher command; later, wider swaths fell under the groups’ sway—beside still-active officials, secret insurgent authorities formed, watching, infiltrating, amending, or stalling their work.

At last, from insurrection rises open revolt: the jus insurrectionis becomes jus rebellionis—gang clashes and street fights fade; like a raging torrent, revolution breaks free, wresting state power from its old masters. Mussolini’s March on Rome stands as one case—after years of bloody strife by the fasci di combattimento, after a long contest for the people’s soul, young Fascism seized the state and won it. Not a few deputies in Italy’s chamber, but the revolutionary toil in streets and cellars, claimed that power for him.

Against which state, then, does this jus resistentiae stand? To err is human fate. Even a good judge’s hundred rulings hold some flaws, maybe even true miscarriages. Every state deals some injustice, for all human constructs falter. Thus, not every single wrong grants a citizen this right. Michael Kohlhaas has justice on his side—but he’s an anarchist fighting a private war. This right doesn’t rise against every state misdeed. Yet against an unjust state, it’s a moral duty. A state turns unjust when it so breaks natural law within itself that only its removal can restore it.

It’s natural law that a people—those of shared blood and tongue—form a state. Thus, the petty states carved in Italy at the Congress of Vienna defied this law, and Italy’s great revolutionaries—Mazzini, Garibaldi, Cavour—acted rightly by natural law in smashing them with force. Poland’s First Partition in 1772 might have lost only foreign lands it once seized in mightier days, but—barring minor non-Polish fringes—the partitions of 1793 and 1795 tore a living nation apart, flouting natural law; Poland’s rebels, from Henryk Dąbrowski to Lelewel, Roman-Traugutt, and Józef Piłsudski, were justified in waging their revolutionary fight.

For Germany, the First Partition—Versailles, 1919—was already a crime against natural law: beyond some foreign patches, pure German lands were ripped from the Reich, and Habsburg Germans, despite their border ties, were immorally barred from joining it. German revolutionaries who fought this wrong were wholly warranted by natural law—and it’s telling that, at Nuremberg, the victor-judges forbade mention of Versailles, the root and deepest spark of what followed. Germany’s second partition in 1945—the expulsion of Germans from ancient holdings, the severing of old regions, the Saar, and vast lands east of the Oder and Neisse—marks the peak of satanic wrong; it’s a total breach of natural law, and all built on it is devil’s injustice, which no thousand years (and it won’t last that long!) could ever legitimize! There’s a natural right to honor, family, and honestly gained property. A state that systematically shames whole classes or groups, strips their families’ livelihoods through work bans, and robs their goods via hate-filled political courts is unjust. It matters not if a pliant or base parliament cloaks this wrong in law—wrong doesn’t turn right by being printed as statute.

There’s a natural right to revere and honor the dead. A state that topples monuments of a grand past, smashes war memorials—denying the last loyal thanks for soldiers’ sacrifice—and paints betrayal as noble and fidelity as "criminal" to its people is so vile within that it must be deemed unjust; there’s a threshold of irreverence that defiles the dead. The dead, too, hold rights to pious memory and gratitude, which no state can steal. A people owns its past as much as its present and future.

There’s a natural right to some freedom—broad where seas guard it, like Britain’s isles, or narrower amid open borders and many threats; but a state enslaving individuals wholly, barring free thought and property’s fair gain, is unjust.

Freedom includes the right of person and people to grow per their traditions and gifts—a right no majority vote or foreign conqueror can erase. Imagine, hypothetically, a left-wing majority in England’s Parliament today axing the monarchy for a republic: despite that fluke majority, every Englishman could resist, backed not just by a stout minority but by the nation’s full tradition. When foreign powers force an unasked, unwanted government on a people, snapping all its traditions in hostility, it’s wrong—a freedom’s breach. That the communist state, wherever foisted on peoples, embodies this freedom’s denial and is thus unjust brooks no doubt.

Yet the democratic Weimar Republic, thrust on Germany by Wilson in 1919 and again by the Western Allies in 1945, was born of force and wrong too.

To the German people’s own sense—barring émigrés, mostly racial exiles—it was a dead-end choice. Free of outside meddling after Hitler’s death, Germany could have birthed any state form, from an evolved National Socialism to a restored monarchy. But Weimar’s democracy was never even an inner pick—it was just foisted anew on Germans, trampling their right to self-shaped growth.

The so-called People’s Democratic Republic in the Soviet Zone is a satellite, a lackey-state of a partitioning power. Its claim to champion Germany’s unity aims only to drag West Germany under Soviet rule. It’s stripped rights, seized property, hounded millions, mocked justice with yesterday’s thieves judging yesterday’s judges, banned free thought, persecuted religion vital to many, defiled the dead’s memory by razing all German past monuments and every war memorial, and runs grim camps—not for career crooks, but the nation’s best. It leans on a tiny minority, rigging votes with terror, gagging the people with bloody force. What’s true of it fits every communist state: by being communist—disenfranchising swaths, denying God, spurning natural law, enslaving men—it’s unjust. Like a wild beast, the communist state strikes if unstruck—none know when they’ll be "taken" and vanish, not for deeds done, but for belonging to a class meant to vanish, for "wrong thoughts," or being "unwanted."

In this "People’s Democratic Republic" case, add that it acts as a Soviet foreign rule’s minion on our soil, its leaders guilty of betraying our eastern lands.

The West German Federal Republic in Bonn, too, is an enemy-made satellite state; its Basic Law—daring to call itself free!—was hashed out point by point by a Parliamentary Council lacking any legal mandate to draft it (the state diets naming it had no writ for a West German charter), settled with foreign generals, and never blessed by a free people’s vote. It binds no one morally or legally.

West Germany, too, ran mass disenfranchisement via denazification—still clinging to it today, though softened—and let the dead be shamed on its ground, like the fiendish ruin of Munich’s eternal watch and the tearing down of many honor-markers. In this, it’s unjust too. It also blocks the people’s will from free voice with half-legal, illegal tricks—proven by the sham penalty for beating Deputy Hedler in the Bundestag itself, terrorizing small right-wing parties, and hounding national forces through denazification courts.

Yet while the People’s Democratic Republic is a hardened, reprobate unjust state, Bonn’s pluralist makeup is a mix of clashing forces—where even faint, checked national leanings vie for voice, shards of worthy officials strive under the mess to do the people’s best, and some perhaps hope this state might one day play Piedmont’s role in Italy’s tale.

No doubt the right to resist stands against Bonn too—but how far it’s wielded hinges on this state’s path: will it prep a better whole Germany and then fade, or stay a foreign power’s puppet against our people? This shapes the final judgment of its leaders. Chancellor Adenauer would gain from reading Count Cavour’s story.

But this issue stretches far past Germany. All old Europe’s cultural sphere lies threatened now. Roosevelt flung wide the West’s gates to barbarism. The Americans’ ghost-chasing of fallen democracies after 1945—thinking twelve blood-rich years could be scrubbed like a wrong sum—built no real strength to guard Europe’s remnant. Now North Americans see something’s snapped here. A reflective watcher, U.S. High Commissioner John McCloy, wrote in May 1950’s Information Bulletin from his Germany office:

“There is a third aspect of the problem which may be the most important: the psychological or spiritual factor. Man seeks loyalties and ideals to which he can dedicate himself and which will give meaning to his daily life. In an earlier day national states provided sufficient scope for this need. Today this is no longer true. Certainly in Germany young men and women feel that their lives are blocked by a dead end. The cause is not only the physical or economic condition of their country. The difficulty is rather that no goal or concept seems to inspire hope or to evoke dedication.

Without such a hope, without a wider horizon, they may again become victims of the demagogue. But within such a hope they may create a free society.

In short, the crucial need is for a genuine European community. The demands of security, of economic and spiritual health all call for the same solution.”

He’s dead right. Germany’s youth see no point in democracy’s return. The Reich was their love, their task, their joy—that’s why the young fought for it so fiercely. Democracy leaves them cold.

It’s much the same with many young French, Italians, and more—they, too, find no sense or mission in what stands. And if McCloy weighs this coolly: do today’s democratic regimes in Europe really seem set to do more for Europe’s unity than Strasbourg’s vague chatter!?

Yet if Europe’s unity is the lone cure and shield against communism’s looming strike, and if 1945’s democratic setups block it—doesn’t it become our duty to resist a regime that, through sheer ineptitude, gambles away everyone’s last rescue shot?

Then those forces—once comrades, shoulder to shoulder against Bolshevism—must take the reins, building on the legacy of divisions from nearly all Europe’s peoples who fought the great fight for Europe. It’s time to save Europe from being pawned by fumbling democracy into communism’s grip, to call a "General Confederation" of the upright, bold, and farsighted to rescue Europe, its timeless moral worth, and forge a "third force." This alliance won’t bypass Hispanity’s might, the Islamic lands’ latent fire, or the endless tradition of sacrifice, pain, and trial Europe holds now. In its ranks will stand all who fought for this Europe—killed, tortured, hunted. No cause worldwide has claimed so many martyrs as this. They bind us to finish the work.

“Se scopron le tombe, se levan i morti, I martiri nostri son tutti risorti ...”

(If the tombs are opened, if the dead arise, our martyrs are all reborn ...)