Reflections on Beethoven's Ideal of Humanity

[Der Weg 1948-10] An original translation of "Gedanken zu Beethovens Humanitätsideal"

Title: Reflections on Beethoven's Ideal of Humanity [de: Gedanken zu Beethovens Humanitätsideal]

Author: Elly Ney

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 02, Issue 10 (October 1948)

Page(s): 682-688

Dan Rouse’s Note(s):

Der Weg - El Sendero is a German and Spanish language magazine published by Dürer-Verlag in Buenos-Aires, Argentina by Germans with connections to the defeated Third Reich.

Der Weg ran monthly issues from 1947 to 1957, with official sanction from Juan Perón’s Government until his overthrow in September 1955.

Source Document(s):

[LINK] Scans of 1948 Der Weg Issues (archive.org)

Der Weg Editor’s Note:

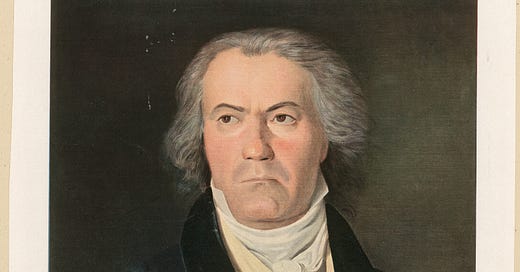

With heartfelt joy, we greet Elly Ney in this space today, a woman who, for decades, has stood as Germany’s most eminent piano artist. Elly Ney, hailing from Düsseldorf, has earned remarkable distinction through her tireless dedication to the musical education of the people—above all, the youth—striving ceaselessly to bring music, and particularly Beethoven, into their lives.

By the close of this piece, readers will find themselves profoundly moved by the deeply German essence of this outlook on life: amidst chaos, confusion, and decay shines a radiant vision of noble humanity—a German woman, peering through the grayness and hardship of these days, discerns the meaning of the future and, with a gesture of quiet trust, points the way forward. For this, she has our heartfelt gratitude!

Reflections on Beethoven's Ideal of Humanity

By Elly Ney

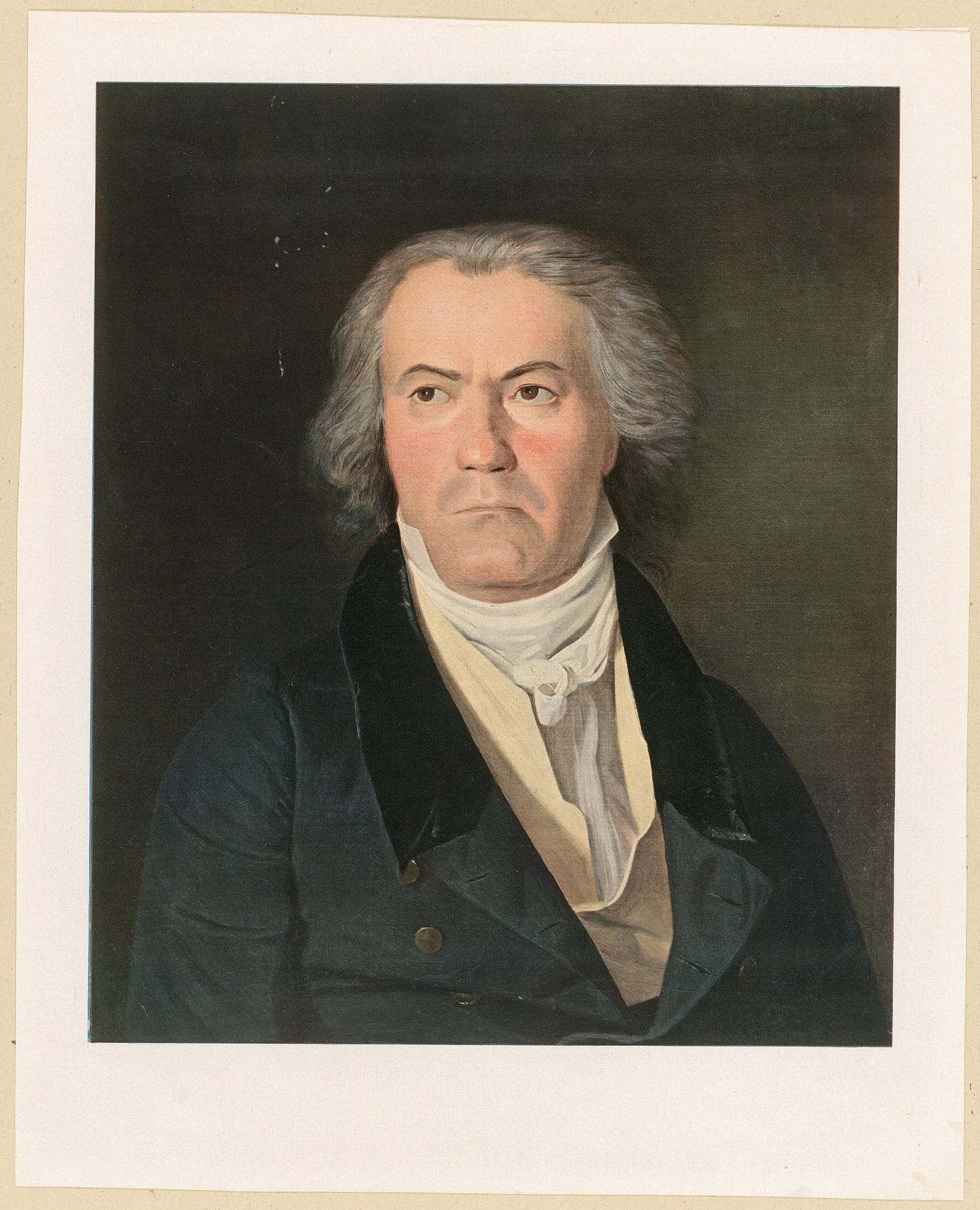

It’s only natural that Beethoven is often linked to the ideal of humanity, for the entire intellectual and spiritual climate of his era was steeped in this noble vision. Yet his passion for the Greeks—their literature, their Egyptian and Greek mythologies—was far from a fleeting trend, as some might suppose. No, it sprang from the deepest roots of his being, driven by a profound longing to nurture the higher, nobler nature within humanity, to shape true humans and guide them toward their ultimate purpose. Countless moving accounts and words from those who knew him paint Beethoven as a friend and grand benefactor to suffering humankind. His own sayings reveal just how deeply the well-being of all people mattered to him:

“Sacred are those who, pressed by suffering, plead for help.”

“You mustn’t live as a human just for yourself, but for others too.”

“Never, from my earliest childhood, could my fervor to serve the poor and suffering through my art settle for anything less—or need anything more—than the inner joy that comes with it.”

“See me as a loving friend of humanity, wishing only good wherever it’s possible.”

Endless notes in his conversation books show the lengths he went to secure the finest education for his nephew Karl. We could list many more stirring traits of his vast humanity, each one a testament to his deep immersion in the ideals of true human love and a mighty quest for freedom—the twin beating hearts of all authentic humanitarianism.

That this ideal saturates his entire artistic legacy, born of his ceaseless drive to fuse life and art, echoes in every note we hear. But we can sense it even more plainly when we turn to his vocal works. His very first choral piece already betrays this humanitarian spirit—I mean the Funeral Cantata on the Death of Emperor Joseph II, penned by a twenty-year-old Beethoven back in Bonn. The image of an “enlightened ruler” might have drawn him in, especially since he was, at that moment, flirting with the ideals of the French Revolution (just like Schiller, and it’s no coincidence both were named honorary citizens of the French Republic). Whatever the spark, the cantata’s choral aria, “Then the people rose to the light,” pulses with the forward-looking, humanitarian faith of the Enlightenment. (Later, in Fidelio, we see this same thought bloom fully in the prisoners’ liberation.)

A year before that, in the birth year of the Eroica, he composed “The Happiness of Friendship” (later published as Op. 88).

In 1814, he crafted the canon “Friendship Is the Source.”

The next year, he returned to a piece (first drafted in 1804) set to Tiedge’s “To Hope,” a text brimming with that same enlightened optimism.

By 1822, he gave us the “Song of the League,” Op. 122, alongside the album leaf “The Noble Man” and the canon “Let Man Be Noble.”

Then came 1823, consumed by the creation of the Ninth Symphony—and there, everything falls into place.

After these few scholarly examples, I’d like now to dig deeper into the heart of it all.

If we set aside a handful of Beethoven’s smaller occasional pieces, his vocal works consistently reveal the care and duty he brought to choosing their texts. Even with something like a mass—where the words mostly echo the same core beliefs time and again—he didn’t settle for the usual Latin text for his Mass in C Major. Instead, he had a German version written just for it. It’s as if he took the Latin, lifted it beyond all borders, and let it sing out in the “temple of nature” in his native tongue—clear to everyone, speaking straight to each soul. He wanted to summon all people, to lift their spirits high. So, for a later edition of the mass, he picked a finer text—“an excellent text,” he called it—far more brilliant than the first, stirring the human heart even deeper. Schindler tells us:

“In April that year, Countess Schafgotsch from Warmbrunn in Silesia brought him his first mass with a new German text, penned by a local music director, Mr. Scholz. We were just sitting down to eat. Beethoven tore open the manuscript, scanning a few pages. When he hit the ‘Qui tollis,’ tears spilled from his eyes, and he had to stop—overwhelmed by the indescribably beautiful words, he said, ‘Yes, that’s how I felt when I wrote this!’ It was the only time I ever saw him cry.”

Beethoven didn’t just want his mass to nudge people into a religious mood for an hour. No, he himself described the grand mission of his Missa Solemnis:

“… my aim was to awaken religious feelings in singers and listeners alike, and to make them last.”

That “making them last” stretches far beyond the personal—it’s about planting a yearning in us for those timeless, eternal values that let us glimpse our truest, deepest core.

With striking vividness, Beethoven summons the perils of war in the “Agnus Dei” of the Missa Solemnis, cutting the peace prayer short with sudden force. Yet his own words above the “Dona nobis pacem”—“Prayer for inner and outer peace”—lift our eyes beyond mere outward strife, toward the real roots of all unrest, which each of us must seek within. It’s worth noting, perhaps, that he didn’t turn to mass texts because of some outside prompt. He chose this path entirely on his own, drawn to it more than almost anything save his symphonies, as he often swore. This pull toward sacred themes flows straight from his deep well of faith—a thread that runs not just through his masses, but through every work he touched.

How marvelous are the words Joseph Schmidt-Görg, the current head of the Beethoven Archive at the composer’s birthplace—where, thank heaven, every scrap of paper survived like a miracle—sets at the close of his study on the Missa Solemnis. He writes:

“The unbloody echo of Christ’s sacrificial death—that’s the essence of the mass itself; the Lamb that lifts away the world’s sins, that grants peace.”

And just as love reveals itself in sacrifice, so too it’s love that ultimately steps forward in Beethoven’s Missa—and, let’s add right away, in its great sister, the Ninth Symphony—in the dual forms of love for God and for neighbor. In the Missa Solemnis, that work he justly named his greatest, where his art hits its peak alongside a towering humanity, the good and the beautiful are wedded. In the strength of this love, propelled by the visions of his artist’s soul, he stands before his brothers in confession and proclamation—one of the great lovers—able to write across the score:

“From the heart! May it go again—to the heart!”

It’s easy to assume that setting a mass to music, purely because of its religious weight, naturally serves the ideal of humanity—especially since the mass underpins the worship of every Christian church, tying the world’s faithful together. So some might not see the humanity in it as something uniquely Beethoven’s. But look closer at his vocal works, and we’re quickly set straight. It’s both moving and telling—proof of how deeply the ideal of humanity soaked into him—when we see him pick texts even for the tiniest form, the canon, that match this vision. Beyond the odd playful jab, we mostly find universal truths or solid lessons turned to song. I’ve already mentioned the canon on friendship and “Let Man Be Noble.”

That same bedrock shows up in how he chose song texts. If we skip over a few occasional pieces—mostly sketches he refused to publish, deeming them unworthy of his name, or ones dashed off for outside reasons—we can still see him guided by pure ethical aims, by the ideals of true humanity and personal freedom, the twin pillars of his humanitarian creed. For him, it’s the idea that matters most—not some poet’s quirky style that he’d keep circling back to, like Schubert with his Goethe songs, Schumann with his Eichendorff cycle, or Hugo Wolf with the Mörike lieder. An ethical aim, a perfect ideal, floats before Beethoven, one he longs to exalt and fix in sound. The words already hold this ideal’s shape. So he scours journals, almanacs, anything, hunting texts where he can simply affirm it.

When Beethoven often picks poems by his great contemporary Goethe, it’s because Goethe—equally drenched in that humanitarian spirit—came closest to the ideal Beethoven held dear, crafting it with genius in his verses. Plus, those poems sing with such music and poetry that, as Bettina von Arnim recalls him saying:

“Goethe’s poems wield a mighty power over me, not just through their meaning, but their rhythm too; they fix me firm and fire me up to compose in that language.”

And more:

“No one’s words could be set to music like his.”

Yet he still turns time and again to lesser-known poets, likely because others—like Schiller and Klopstock, favorites of his too—“start too high up already,” as he put it. Maybe they left him too little room to move, no chance to lift their poetry higher with his music. Still, even these texts rest on timeless truths and noble aims, often spiced with a delicious humor or jest. He’d never stoop to trite or shoddy words—and he even said he couldn’t have set the kind of texts Mozart did.

Because Beethoven keeps aiming to rouse us with a core truth, to nudge us toward our true calling, you’ll rarely find him setting ballads or storytelling poems. The unfolding drama—physical or emotional—barely stirs him; he cares only for the story’s end, the universal, the eternal worth. That’s why, from Schiller’s The Maid of Orleans, he takes just the final line:

“Short is the pain, and eternal is the joy.”

And from Act IV of Wilhelm Tell, the closing words:

“Swiftly death approaches man.”

Often, we encounter direct expressions in the texts Beethoven selected. Imperatives and questions abound, as if he sought to address each person individually, urging them toward the ideal that loomed before him. Consider examples like":

“Rejoice in life” (Canon)

“Speak up when it concerns a friend” (Canon)

“Learn to be silent, O friend” (Canon)

“Eternally yours!” (Canon)

“You must now unbind yourself” (“Resignation”)

“Boldly striving toward the goal, living faithfully only for hope” (“Hope,” Op. 82, No. 1)

“Fear, love, praise God” (“The Quail’s Call”)

“Man shall hope! He shall not question!” (“To Hope,” Op. 94)

“Think, O man, of your death! Do not delay, for one thing is necessary” (“On Death”)

“Who bears the heaven’s countless stars?” (“The Glory of God”)

“And what is it that I may still have to live?” (“On Death”)

“Have you not allotted love to every creature’s life?” (“Sigh of an Unloved One”)

“Do you see the glorious fruits in the field?” (“The Quail’s Call”)

“Is this a man whose word one can trust?” (“The Man of His Word”)

For Beethoven, the sole criterion in choosing a text was its capacity to advance and uplift humanity—not its “lyrically surging emotion.” He wielded history with utter freedom, plucking single stanzas from multi-verse songs or fusing two distinct poems into a unified whole. His textual alterations are especially telling. In a sketch for Gleim’s Anacreontic poem Fleetingness of Time, the original reads,

“I want to enjoy myself while I still can,”

yet Beethoven’s idealized revision states,

“Therefore, I will make use of the time while I still can.”

His fervor to inspire every individual shines through in his frequent insertion of “yes” into phrases—think of:

“Yes, you must now unbind yourself” (“Resignation”)

“Refinement is its goal, yes, its goal” (Ruins of Athens, Op. 113, No. 7)

“Noble, noble, noble action, yes, noble action, be his most beautiful calling” (“Lobkowitz Cantata”)

“Yes, I have done my duty” (Florestan’s aria, Fidelio, Act II)

“Love will achieve it, yes, yes, it will achieve it” (Fidelio, Act I, Leonore’s aria)

“Let man be noble, helpful, and good, yes, good” (Canon)

Beethoven’s all-embracing spirit could shatter every boundary, lifting itself beyond the self into the realm of the universal, the quintessentially human. Thus, it feels entirely natural that he transcended his homeland’s borders, reaching beyond the naturally given to seek the timeless and universal among other peoples. His foreign songs outnumber his German solo songs by more than double. For five years, he immersed himself in arranging Scottish, Irish, Welsh, and Italian folk songs, even envisioning a grand collection titled Chansons de divers nations. Though this project never came to fruition, and most of his folk song arrangements went unpublished, traces of Scottish, Irish, Russian, and Croatian melodies in the scherzos and finales of his works reveal his love and profound empathy for foreign souls. His Scottish songs stand as vivid proof of this.

What Beethoven deemed “truth” towered above the emotions stirring within him. Yet this never suggests his music dwells in the intellectual realm—far from it. The words he inscribed above the Missa Solemnis resonate across his entire oeuvre. No emotion was alien to him. But he did not merely aim to voice his own feelings; he elevated them into the supra-personal, refining them to perfection. Beethoven sang of suffering, joy, and pain. Even in his love songs, he soared beyond the narrow confines of subjective emotion into the objective sphere, where all-encompassing love glows in its purest form.

“In the word love lies the principle of all humanity,”

declares Austrian poet Robert Hamerling. Strip Beethoven’s songs to their core, and this humanitarian principle emerges clearly: love for God, love for one’s neighbor, love for nature, love for suffering creatures (Elegy on the Death of a Poodle), love for the homeland, love for other lands, love for universal truths, love for the good, the beautiful, the true, love for freedom. Every admonition, every call, every awakening of humanity sprang from his deep devotion to the ideal of the true human being he so fervently yearned for.

It’s no wonder he seized the libretto of Fidelio with genuine passion. Here, love ascends to its highest, most perfected form: the willingness to sacrifice oneself for another. Beethoven allows Leonore to transcend herself, becoming the ideal embodiment of love. He didn’t wish to depict just any lover, as many composers of his era did in their operas; instead, he intensified Leonore, raising her to a genius of humanity, an ideal for all mankind. This vision of love merges powerfully with a striving for freedom, together forging the ideal of true humanity.

“To love freedom above all,”

a phrase Beethoven cherished from his youth, was a driving force. In Fidelio, we find this ideal glorified.

“The sacrifice of one human for another and the liberation of suffering fellows were, to him, worthy of the highest praise and most piercing sermon,”

writes Richard Benz in his essay “Beethoven’s Spiritual World Message.” When his gaze, lost in solitary reflection, peered into the world’s darkness, searching for those rare beams of light amid the gloom, his unquenched love for the individual fused with his love for humanity. This fulfillment crests in a global jubilation that, in the opera’s final chorus, foreshadows the Ninth Symphony.

“The opera earns me the martyr’s crown,”

Beethoven wrote, after relentless demands for revisions. Nearly a decade passed before audiences began to grasp what he sought to convey through Fidelio.

Yet it was the Ninth Symphony that truly carried Beethoven’s “world message” to all people, embraced by humanity like a Pentecostal revelation.

“In the chorus of human voices he summons in the symphony’s final movement, he at last created the humanity he could not embrace in life,”

Benz observes. Here, the world understood the solitary genius through the human word. That this word—joy—rang out first and alone, voiced by human throats, must have felt like a consecration of humanity’s calling. No other modern artwork has been celebrated as a festival, nearly akin to a religious rite, like this final symphony. For a fleeting moment, humanity stood ready, a new community united with the lone prophet in sacred joy.

Beethoven knew no limits; the ideal was his horizon. With every note, he reached for this ideal, beckoning others to follow. Strip the text from his vocal works, and the music’s power remains undeniable—it captivates us, shaping us into better, nobler beings. Recall the line from Fidelio:

“May you be rewarded in better worlds.”

Can we imagine someone touched by these sounds harboring ill thoughts or committing a wrong? Examples abound. Words offer a concrete vision of the distant ideal we crave; his tones flood us with the impulses of true humanity. With all his spirit’s might, he lifts the individual to the pinnacle of pure humanity, each note a summons to transform ourselves into true human beings, to grow toward the ideal.

The path is steep.

“Beethoven’s message is not easy,” Benz writes. “It carries a vast ethos, a world message for all: it demands we see our brothers in others, that millions truly embrace one another—a renunciation of selfish desires, of subjugating those who differ in faith or thought, of chasing mere material ends. Like the Christian message, it holds all practical demands of faith. Yet in wordless tones, it weaves the spiritual evolution and soul-experiences of Western centuries, a planetary freedom surveying the world beyond any single tongue. This empowers it to speak to all peoples, awakening in souls the secret of their being, each translating it anew in a timeless Pentecostal miracle.”

Eulogy for Ludwig van Beethoven

Franz Grillparzer

“Here lies a man who lived with extraordinary passion. His life was defined by a single, unwavering purpose: he pursued one goal with all his heart, cared for one ideal above all else, endured hardships for one cause, and gave everything he had for one vision. If anything stood in his way, he removed it without hesitation and continued forward, always forward, toward his ultimate aim. In our fragmented world, if we can still find a sense of wholeness within ourselves, let us gather at his grave. For this is why there have always been poets and heroes, musicians and those inspired by a higher calling: to help us, the weary and the lost, to stand tall, to remember where we come from, and to keep our eyes on where we are going.”