The Land of Israel and World Jewry

A Critical Analysis of Israel's Establishment and Jewish Diaspora Dynamics

Title: The Land of Israel and World Jewry [de: Erez Israel und das Weltjudentum]

Author: Martin Faustus

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 06, Issue 11 (November 1952)

Page(s): 755-763 [LINK]

Dan Rouse’s Note(s):

Der Weg - El Sendero is a German and Spanish language magazine published by Dürer-Verlag in Buenos-Aires, Argentina by Germans with connections to the defeated Third Reich.

Der Weg ran monthly issues from 1947 to 1957, with official sanction from Juan Perón’s Government until his overthrow in September 1955.

This analysis by Martin Faustus critiques the establishment of Israel, highlighting the Zionist movement's role, the challenges of Jewish statehood, and the complex dynamics of the Jewish diaspora, particularly in America. It also examines the financial and political struggles of Israel, the influence of Jewish organizations, and the uncertain future of the Jewish state.

The Land of Israel and World Jewry

by Martin Faustus

When, amid the chaos of the post-war period, the Jewish state was born in Palestine against the will of the British Mandate authorities and under Arab resistance, it already bore the seed of discord within itself. This duality, a shared trait of today’s humanity, manifests as inner turmoil and rootlessness, arising from the uprooted soul of Western man and his distance from God.

How grandly the great men of the Middle Ages acted, bound to God within and filled with a cosmic sense that transcended both the rigid forms of Scholasticism and the tyrannical shackles of church dogma. Like mighty Gothic cathedrals, these geniuses soar toward the heavens: a Meister Eckhart, a Paracelsus, a Luther, a J.S. Bach, and many others. Even Goethe, the greatest of Western men, still carries the stamp of monumental unity and reveals a cosmic empathy that always and everywhere allows him to reach the source of divine knowledge.

With the Age of Enlightenment and the waning of the Middle Ages, pure intellect replaced genuine religious feeling and cosmic connection, seeking to resolve and explain all problems of existence through reason and the critical mind. Rationalism also shifted the political outlooks of nations, freeing the rigid masses of Jewry from the ghetto. Until then—save for language and milieu—there were scarcely any notable differences between a ghetto Jew of the East or West; this changed the moment the prison doors opened in the West.

When Western Jews emerged from the stifling air of the ghetto, from the darkness of Jewish alleys into the light, and stepped into the liberal realms of the Enlightenment, they received the intellectual treasures of Western humanity from the hands of European nations. Until that point, the tyranny of a despotic law had held them together, distorting their entire sense of life and stifling every liberal thought with heresy-hating brutality; now, with their characteristic eagerness to learn and virtuosity, they swiftly adopted Western cultural goods. With a recklessness honed over millennia, they soon pushed themselves to the forefront, imprinting our era with the mark of their corrosive dialectic—a meaning captured in the words of Jewish philosophy professor Hermann Cohen:

"Only thought can produce what may count as being."

Today, one can practically speak of a mental Judaization of the West. Thus arose the world Jewry of the West, present in influential positions across all governments, serving only its own interests under the guise of various nationalities.

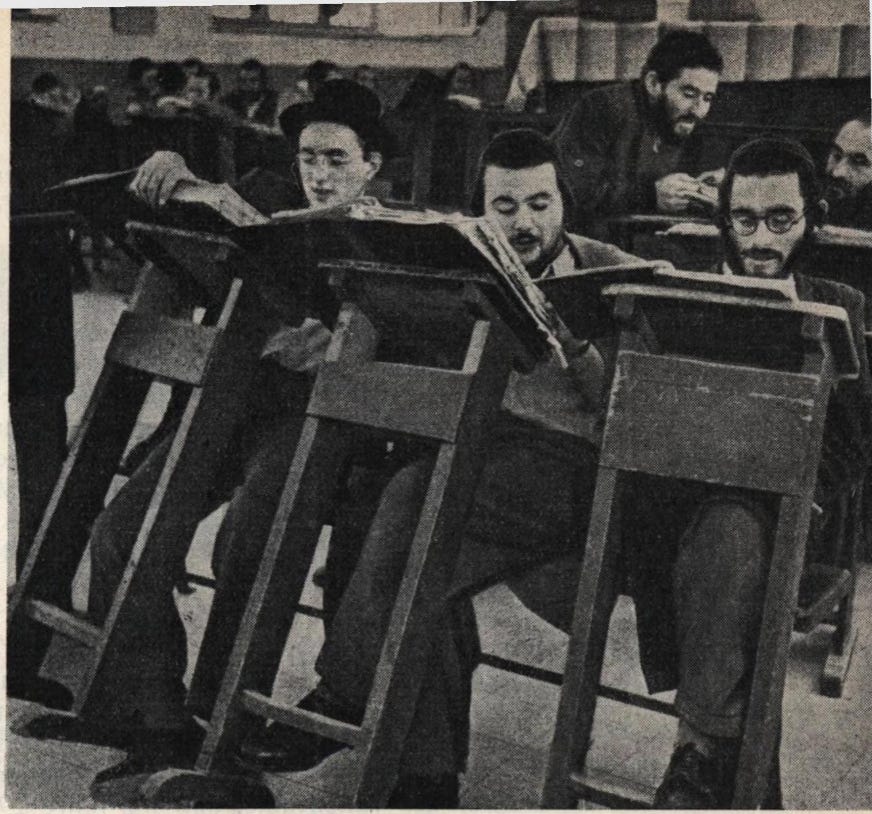

This world Jewry now found itself in opposition not only to the non-Jewish world but also, it seems, to Eastern Jewry, where emancipation crept forward slowly within its closed mass. While Western Jewry appeared to assimilate—and did so to some extent—Eastern Jewry sought paths that promised not dissolution but a reconnection with their ancient traditions. In Hasidism and the Haskalah, it believed it had found them. Hasidism, this new Jewish mysticism, yearned for a higher sense of life, while the Haskalah, a new Jewish enlightenment, saw its mission in freeing thought from the "Law."

In 1895 and 1896, Theodor Herzl wrote his book The Jewish State in Paris, a guide destined to stir the fermenting mass of Jewry. This led to the convening of the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897, where Herzl was elected president. Herzl was a pure Western Jew, tied to Eastern Jewry only by race, with no bonds of education or tradition. Thus, this Western Jew, lacking Jewish upbringing, gave Jewry a movement not born of an inner necessity rooted in Jewish folkdom but conceived solely as a defense against the antisemitism still afflicting Eastern Jews.

Before Herzl, others—such as Pinsker, Hess, and Birnbaum—had grasped the issue more deeply, at the core of Jewish folkdom and tradition. But Herzl was no theorist or analyst; he was a man of action who brought his vision to life. Therein lies his greatness for Jewry.

Through the Zionist movement, the latent opposition between Eastern and Western Jewry came into the open, splitting Jewry to this day into two camps: Zionists and anti-Zionists. Despite fierce rejection by most Western Jews and the resulting resistance—even rabbis blocked a Zionist Congress in Munich—Herzl pressed forward, organizing, financing, and realizing his vision. Beyond a few Jews in Jerusalem and a small settlement in Rishon LeZion, founded in 1882 by Russian émigrés who struggled until Rothschild’s aid, Palestine was then nearly "free of Jews."

To bring settlers there in greater numbers, the Sultan’s consent was needed, as was his approval for purchasing larger lands. One had to tread carefully to avoid offending the "Sublime Porte." Yet the world gained a curiosity! The biblical people of shepherds and cattle traders, of hucksters and bargainers with Jehovah, now cast as farmers!!

Financing came through shares called shekels, which every Zionist had to buy, granting voting rights and eligibility for the Zionist Congress—one delegate per 3,000 shekels. Shekels of Zionists in Palestine counted double, a practice still in place. When this effort faltered, H. Schapira founded the Jewish National Fund (JNF) on December 29, 1901, making it the Zionist movement’s bank, open to contributions from any Jew without obligation. To erase traces of the now-despised German language, the JNF was later renamed Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael.

World War I gave the Zionist Organization tremendous momentum; through its influence and the services world Jewry rendered to the Allies, it pressured Britain into compliance. On November 2, 1917, Balfour issued the Balfour Declaration for a Jewish national home in Palestine. Bitter disappointment spread among Jews when the Churchill White Paper of June 3, 1922, separated Transjordan and tied immigration to Palestine’s economic capacity. Expecting the whole, they received half; hoping for sovereignty, they stood under British Mandate.

The Zionists then established the Jewish Agency, the sole body authorized by the Mandate to handle the return of Jews from exile (Kibbutz Galuyot) and related matters—an executive organ of a "government in waiting." After World War II, against Britain’s will, violent mass immigration to Palestine sparked fierce clashes between Jews and British forces. These persisted until a Jewish majority in the United Nations (UN) proclaimed Palestine’s independence, birthing Erez Israel in May 1948. No sooner had this occurred than the land’s rightful owners, the Arabs, declared war on the new state. Arab disorganization, Transjordan’s betrayal, and Israel’s modern weapons secured its "victory."

Now the Zionists could begin building and organizing the new state, a Western democracy modeled on Switzerland. The gates of "Erez Israel," as the state is officially named, were flung wide to welcome all who wished to enter. This was proclaimed worldwide, yet those who stayed away were the Maccabees, the proud Jews, and the young Chalutzim (pioneers) expected to storm Israel’s borders. Those who came were the displaced, the oppressed, the persecuted—survivors of the post-war era, a weary, broken generation.

Still, official figures state Israel now has 1,700,000 inhabitants, including 135,000 Arabs. Prime Minister Ben-Gurion, on a trip to America, claimed 10% of the world’s Jews live in Israel, implying a global Jewish population of 15–16 million—a figure aligned with serious statistics, refuting the daily horror tales of the international Jewish press about six million murdered Jews.

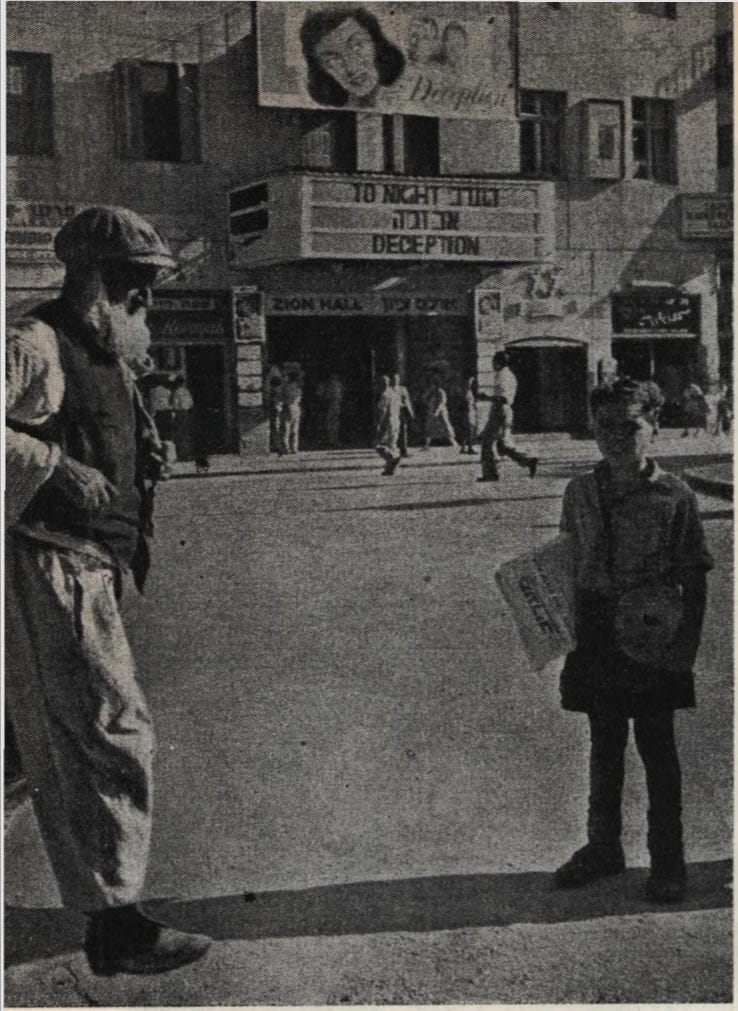

Among immigrants, 10% are unfit for work, burdening the state. Behind Tel Aviv’s gleaming facade—self-styled the Paris of the East—lies stark poverty; 40,000 residents, or 10%, rely on welfare or charity packages. Tellingly, of 700,000 immigrants, only about 10,000 were Western Jews—less than 2%. Of these, 7,000 came from Western Europe, 2,200 from South America and Africa, and—astonishingly—1,200 from the USA, Israel’s supposed hope.

Surveys in Holland, Belgium, and France show little interest in Israel; Jews there wish to emigrate, but to the USA. Much has been written about why American Jews stay away, yet the core of American Jewry—Eastern Jews who fled Russian pogroms since the early 20th century—settled in New York, now the world’s largest Jewish city with three million Jews. After 1933, German Jews arrived, aided by Roosevelt’s generous quotas; by 1939, Broadway echoed with more German than English.

Remarkably, this orthodox Eastern Jewry, fresh from the ghetto, was absorbed by American civilization’s leveling force within one or two generations. Alarming to Jewish leaders: in 1951, of 635,000 preschool-age Jewish children, fewer than 50% received Jewish education, and 95% in higher schools had none. Mrs. Halperin, head of Hadassah, the largest Zionist group in North America, struck a chord at the last Zionist Congress in Jerusalem, declaring no mass immigration of Chalutzim from America can be expected. Why? Her formula: North America is diaspora, not Galut.

Though Galut mirrors the Greek "diaspora," she distinguishes them: Galut is the inferno—ghettoes, persecution, Nazism—while diaspora is paradise, freedom, equality, the USA.

For Eastern Jews, the promised land is not Palestine but America—and who can blame them for refusing to trade this land, where they hold sway, for a forced ghetto in Erez Israel? Slogans like "Home to the Reich" fall flat; grand phrases of "blood and soil" or "sword and labor nobility" fade like a preacher’s voice in the desert. What awaits the immigrant in Erez Israel, this Western-style democracy with no return once the door shuts? Tears, sweat, and blood, as Churchill might say: mail and press censorship, scant rationed food, housing in tents and barracks fit for chicken coops or cattle sheds, in border colonies built for strategy, where—per Ben-Gurion—he can forge "a chain of security from human steel."

This demands strong idealists with endurance, strength, and courage to swap diaspora comfort for the harsh toil of a desert settler, perhaps risking life for a state all its neighbors oppose, biding time for a second round.

Building a state requires not just people but vast funds. Israel’s finances are perpetually shaky. Imports of 880 million dollars dwarf exports of 108 million. The deficit floats on short-term bonds, forced loans, and pound devaluation, eroding the currency.

Immigration costs fall not to the state but to Zionist groups, the Joint, and the World Jewish Congress, which report a one-billion-dollar shortfall—uncollectible due to Israel’s insolvency. During the war, tensions between these groups subsided, but post-statehood rigidity gave way to sharp divides. The fight for power, influence, and dollars rages on all fronts—between Israel and the diaspora, and within the diaspora among Zionist factions and other mighty groups. Ben-Gurion’s rebuke of American Jews for sending money but no pioneers sparked bitterness, worsened when Israel launched a 500-million-dollar bond drive in the USA. The Joint, backed by powerful Jewish finance, refused to fundraise during this action.

Yet the mightiest group is the World Jewish Congress, founded in 1936 by the Zionist Congress as Jewry’s umbrella body, marked by its venomous hatred of Germany and its meddling in governments when Jewish interests seem threatened. Recognized in the United Nations (UN) Charter as a non-governmental organization, its influence largely drove the "Judaized" UN to proclaim Israel’s independence. It demanded special status from Israel’s government, as did the Zionists and Jewish Agency. Israel resisted, yielding only to Zionist Congress pressure for the Jewish Agency’s status—negotiations remain fruitless.

American groups hoped to end fundraising in 1951, but the government insisted on a decade more. The World Jewish Congress learned its budget deal with the Jewish Agency, tied to fundraising income, would not renew past 1951.

Then the World Jewish Congress struck back. Behind closed doors, barring press and public like thieves in the night, its New York conference tackled reparations from Germany. Allies were "advised" to order Germany to negotiate; its Bonn delegates met Adenauer, who democratically granted over half their demands without consulting Germans. Israel faced an ultimatum:

“Negotiate via us, or we pay nothing more!”

Outrage flared among Zionists.

“Negotiate with Nazis, this nation of war criminals and murderers? Never!”

Menachem Begin, ex-Irgun Zvai Leumi commander, roared:

“Our brothers’ blood cries for vengeance!”

threatening a coup. New York replied:

“Pecunia non olet. We demand all or nothing.”

The Knesset passed narrowly. Now West Germany props up a bankrupt state’s fading life.

To speculate on Jewry’s decline from its disputes would be misguided. A "supreme leadership" looms above all groups, unknown to average Jews and non-Jews alike. The purposeful Jewish drive for world domination shines through the all-Jewish secret societies of B’nai B’rith, the Alliance Israélite Universelle, and international Freemasonry. The "superiors," likely rabbis, stay shadowed.

B’nai B’rith and the Alliance dominate non-Jewish Freemasonry, closed to outsiders, yet B’nai B’rith accesses all global lodges, while the Alliance, founded in 1860 by Adolphe Crémieux, sits in Paris, tied to the French Grand Orient. It’s assumed Allied politicians in both world wars were high-degree Freemasons; Jewish ones were B’nai B’rith or Alliance members—think Morgenthau, Brandeis, Mack (Zionist), Warburg, Elkus. In America, all Jewish power lies in B’nai B’rith; non-Jewish, in lodges. So too in England and France.

From an orthodox Jewish view, degeneration has grown since the Enlightenment, especially recently, as with non-Jews. Their issues aren’t new—just current. Diaspora has always existed; a state lasted until Jerusalem’s fall. Even then, of eight million Jews, only 2.5 million lived in Palestine; four million spanned the Roman Empire, one million Babylon.

The ghetto was their strength, living by tradition—the "Law." Their religion, Moses’ Law, is a racial code from Aryan roots. While they keep their blood pure, they endure as a race, distinct from Gentiles. Stray from the Law, with its dire curses, and even Yahweh can’t save them—they’ll vanish as a race.

When Ezra reshaped Hebrew tradition for Judaism, he first purged non-Jewish wives. Zionists, the Jewish chauvinists, would force all into Israelis, stoking Jewish conscience against assimilation—especially German—unable to replace German culture with new lands’ ideals. They paint "devil Hitler" endlessly, even denying Jewishness to dissenters. As if it’s that simple!

Spain’s forced converts, now pure Catholics, still betray Jewish traits physically. Zionist methods fuel antisemitism; many non-Jews, reflecting, see a Jew can only be a Jew, willing or not. How long this Jewish state lasts is uncertain now. Surely, only a minority will dwell there; most Jews will stay in Galut or diaspora, needing Gentiles like air to breathe. Why? Deuteronomy 23:20 tells us:

"You may charge interest to a foreigner, but not to your brother, so that the Lord your God may bless you in all you undertake in the land you are entering to possess."