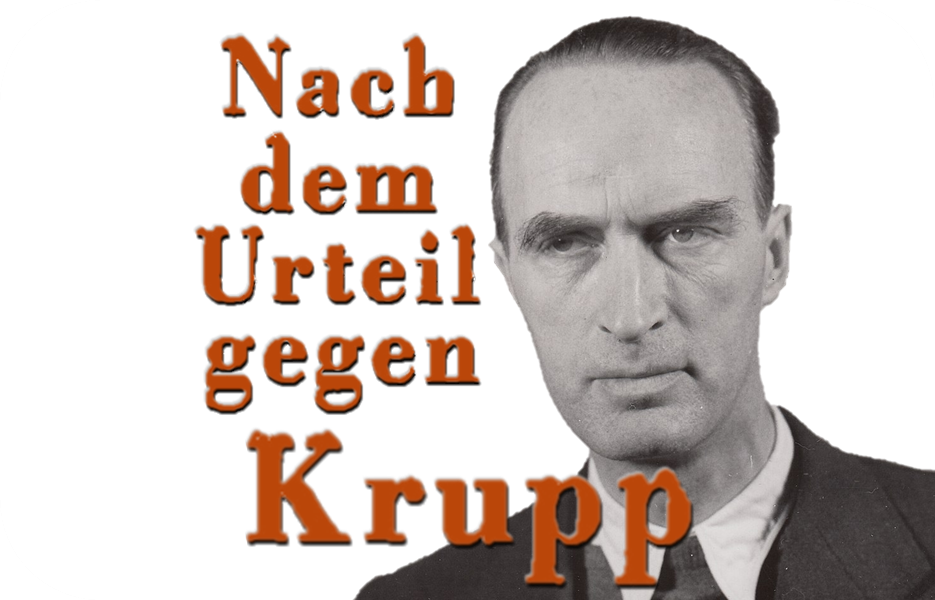

After the Judgment Against Krupp

[Der Weg 1948-11] An original translation of „Nach dem Urteil gegen Krupp“

Title: After the Judgment Against Krupp [de: Nach dem Urteil gegen Krupp]

Author: Th. Krausewall

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 02, Issue 11 (November 1948)

Page(s): 807-812

Dan Rouse’s Note(s):

Der Weg - El Sendero is a German and Spanish language magazine published by Dürer-Verlag in Buenos-Aires, Argentina by Germans with connections to the defeated Third Reich.

Der Weg ran monthly issues from 1947 to 1957, with official sanction from Juan Perón’s Government until his overthrow in September 1955.

This article discusses the events of the Krupp Trial.

Source Document(s):

After the Judgment Against Krupp

by Th. Krausewall

The verdict delivered on July 31, 1948, by American Military Tribunal No. 3 in Nuremberg, in the case of the United States of America versus Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach and eleven senior executives of the Krupp firm, stands out for its extraordinary severity. Alfried Krupp was sentenced to twelve years in prison and stripped of his entire fortune; the other defendants received prison terms of up to twelve years. One defendant walked free, acquitted.

Mr. Max Mandellaub, perhaps the most fervent prosecutor in the Krupp Trial, spoke to the press with evident satisfaction, hailing the verdict as “one of the most significant contributions to international criminal law” (Neue Zeitung, Munich, August 4, 1948). The defense, however, voiced their bitterness, decrying it as a political judgment; they found its language “uncompromising, didactic, and utterly devoid of understanding,” and pointed out that the Krupp fortune had been confiscated—a penalty not even imposed on “major war criminals” like Göring, Ribbentrop, or Streicher, nor in any other Nuremberg proceeding.

Thus, the views of the prosecution and defense on the Krupp verdict clash with stark intensity.

This sharp divide between prosecution and defense has persisted unchanged since the Krupp Trial’s very first day. The American prosecution, after all, had to stake out an extreme position to even mount its case in the Nuremberg economic trials, while the defense had to fiercely counter accusations they deemed, in part, downright absurd.

At the heart of the prosecution’s claims lay the charge that the industrialists—here, Krupp—had conspired with Hitler to plan and wage aggressive wars. Should a conspiracy with Hitler prove untraceable, the prosecution went so far as to posit an alternative “Krupp conspiracy” of their own devising. The accusation of abetting aggressive wars formed the indictment’s core, with political and propagandistic motives evidently outweighing the shaky, hastily assembled legal arguments. Aimed at broadly defaming German industry, this charge crumbled with the stunning partial acquittal on April 5, 1948. Krupp and his directors were cleared of crimes tied to aggressive war and conspiracy shortly after the defense began its case, the tribunal offering the plain rationale that the prosecution had failed to muster sufficient evidence. It marked a clear defeat for the prosecution—and a sweeping rehabilitation for Krupp. The trial’s entire propaganda had hinged on branding Krupp, the cannon-maker and warmonger, for eternity, only to erase him thereafter. That “erasure” dovetailed neatly with the schemes of American left-wing politicians and the Morgenthau Plan’s vision of pastoralizing Germany. Dismantling and seizures at Krupp would have found ready justification in a court-confirmed role in aggressive war crimes! The prosecution felt the April 5, 1948, acquittal as a crushing blow to their arguments; the defense chalked it up as a triumph. Yet the defense soon sensed unease—that this early acquittal might stiffen the tribunal’s stance on the charges still in play.

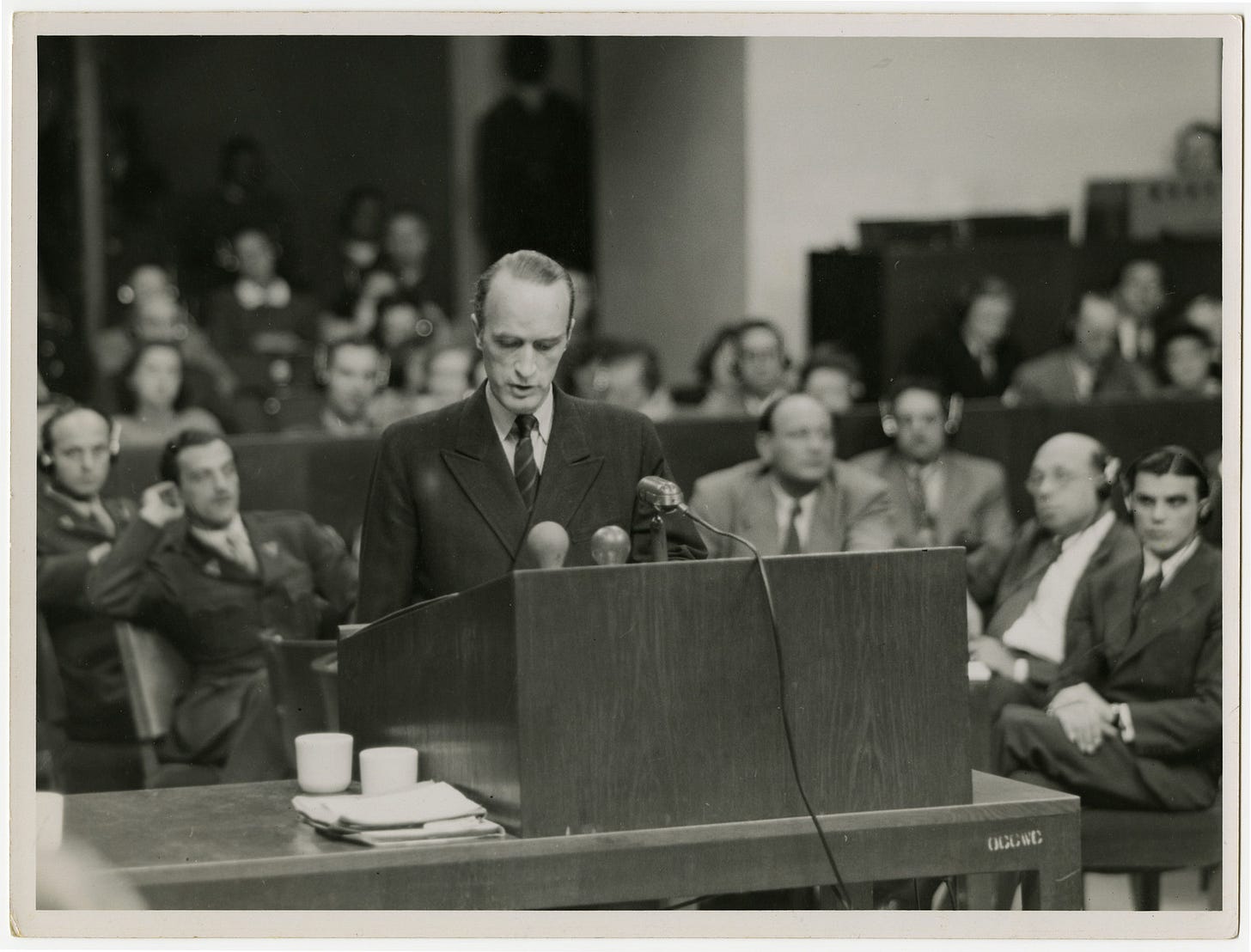

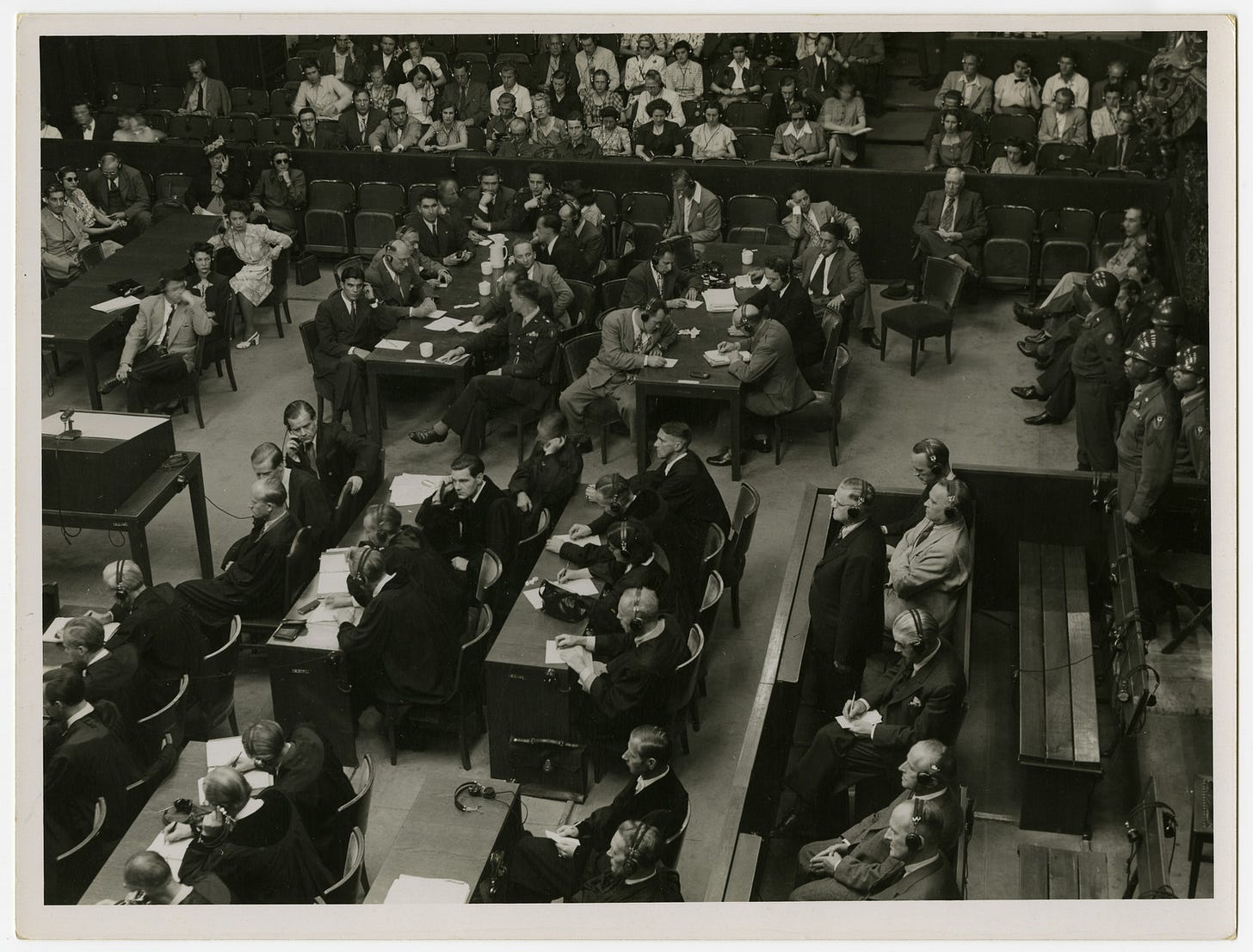

From April 5, 1948, onward, the Krupp Trial narrowed to the charges of “plunder” and “slave labor.” Here, too, the accusations sprawled wide, the trial materials towering in volume. Here, too, prosecution and defense remained at irreconcilable odds. Prosecutors—General Telford Taylor, Mr. Thayer, Mr. Raglan, Mr. Mandellaub, Mr. Brilliant, Mr. Kaufmann, Mr. Koessler, and Miss Goetz—backed by assistants Mr. Issermann and Mr. Buxbaum, battled doggedly to see their views prevail. On “plunder” and “slave labor,” the verdict handed them a resounding victory, the tribunal siding broadly with the prosecution’s stance.

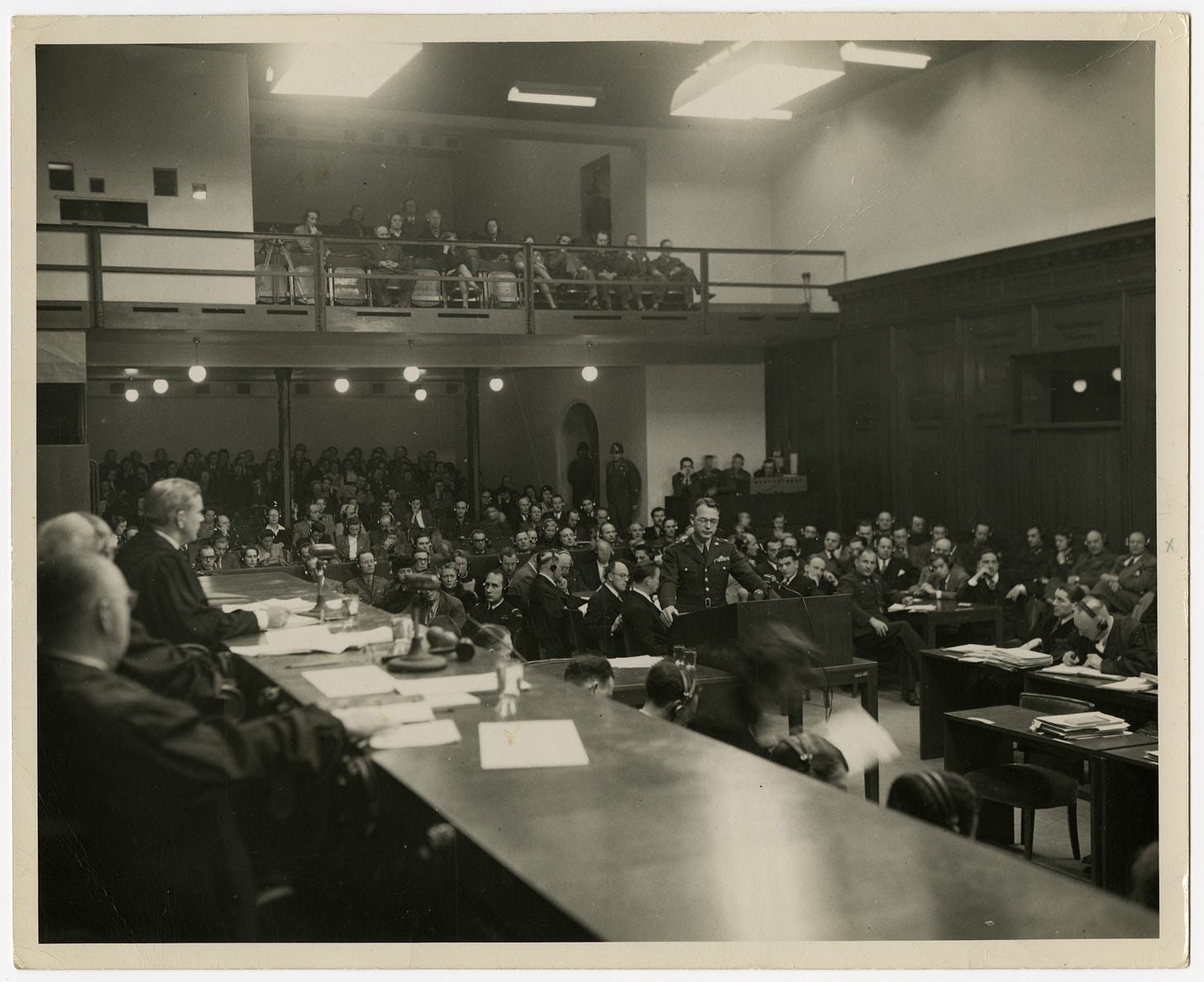

More than in any other Nuremberg Trial, a deep rift emerged—not just the natural clash of prosecution versus defense, but a swift and profound divide between tribunal and defense. The tribunal—Judges Anderson, Daly, and Wilkins—left no doubt from day one that it meant to play hardball. The defense, twelve lawyers strong with some fifteen to eighteen aides, fought back as best they could within their limits. An American attorney, joining the otherwise German defense team months into the trial, changed nothing; the court treated him even more harshly than his German peers. Clashes between tribunal and defenders turned ugly more than once, the air often thick with tension. The judges’ demeanor and tone had the defense and their clients fearing bias and intransigence from the outset.

When Alfried Krupp, after a grueling search for counsel in the United States, secured American lawyer Mr. Caroll as his defender—prompting his German attorney Kranzbühler to step aside—the tribunal dismissed Caroll on bureaucratic grounds, reinstalling Kranzbühler as official counsel against Krupp’s express wishes.

When the defense mounted a vigorous protest against the alien and prejudicial use of “commissioners,” the tribunal had several lawyers hauled from the courtroom by American military police, charged with the equally unfamiliar offense of contempt of court, and locked in the same prison as the defendants. A multi-day proceeding against the arrested defenders followed—an action jarring by European standards—only to end abruptly with the court’s shift to leniency, meting out a mere three-day sentence. Motions from the defense to disqualify the tribunal for bias went nowhere. Overriding their objections, commissioners were installed: first one, then two, then three. These delegates acted as judges beyond the main hearings, splitting proceedings into two or three parallel tracks at times. The judges were left sifting through heaps of commissioner transcripts. Naturally, these commissioners swung into action chiefly during the defense phase. Of 86 prosecution witnesses, 66 faced the tribunal, 20 a commissioner; of 141 defense witnesses, 41 appeared before the tribunal, 100 before commissioners. To the defense, these parallel hearings flouted two bedrock European principles of modern criminal law: immediacy and orality. Keeping pace with the trial’s ever-swelling, fast-moving mass of material grew technically near-impossible for the defense—and, surely, no less daunting for the tribunal itself.

Beyond that, the tribunal heaped near-unbearable time pressure on the defense—and itself. In open session, it declared the judges on loan from their home courts for only so long, loath to overstay their leave. Hearings spilled into Saturdays and holidays; deadlines were imposed or haggled over in grueling talks; haste was a constant drumbeat. For closing arguments, the defense got a scant ten days to prepare. The final trial transcript landed in their hands just five days before the first closing plea. This breakneck pace taxed defenders, prosecutors, and judges to their limits—and the defendants, too, who endured draining daytime sessions only to face hours-long evening huddles with counsel. The defense made it plain—repeatedly on the record—that this relentless rush hobbled their efforts.

The Krupp Tribunal revealed more internal discord than any other Nuremberg proceeding might have betrayed. An older, seasoned presiding judge, grown cautious and restrained, faced two younger, sharper associates who seemed to overrule him often. The tribunal’s practice of rotating the chair only bolstered the associates’ sway.

That discord shines through in the verdict. The Krupp judgment—a singular oddity in Nuremberg practice—spans no fewer than seven key documents:

the partial acquittal of April 5, 1948, on “aggressive war” and “conspiracy”;

the Opinion of June 11, 1948, justifying that acquittal;

Presiding Judge Anderson’s Concurring Opinion, a 70-page take with its own flair yet matching the outcome;

Judge Wilkins’ Concurring Opinion of July 31, 1948, on the acquittal, voicing a far harsher view that just barely cleared the bar;

the July 31, 1948, judgment on “plunder” and “slave labor”;

Anderson’s Dissenting Opinion of July 31, 1948, on that judgment, rejecting asset confiscation and sentence severity while lamenting ignored mitigating factors; and

Wilk Dissenting Opinion of July 31, 1948, on the same.

Hardly a clear, unified ruling!

The July 31, 1948, judgment and its twin dissents also raise eyebrows over majority support: no true majority backed either the guilty verdicts or the sentences. Anderson and Daly aligned on guilt, Wilkins diverged; Daly and Wilkins agreed on penalties, Anderson balked. In the end, only Daly—a lone voice—fully endorsed both guilt and punishment!

The presiding judge, looking like a broken man especially as the verdict was read, distanced himself from his colleagues’ harsh sentences with a visible gesture: he pointedly left their pronouncement to his two associates, whose terms he disavowed.

The verdict’s impact—through its weighty substance and its wording—struck hard. Even the prosecutors seemed caught off guard, some almost abashed by their outsized win. Asset confiscation surfaced only late, in General Taylor’s closing plea. Alfried Krupp’s defender, Kranzbühler, fired back the next day, sharply rebuking it: “They speak of justice but mean money!” Defendants and counsel saw their darkest fears dwarfed by the outcome. Politically, they’d deemed confiscation unthinkable—yet here it was, handing the Krupp firm to the Allied Control Council, a quarter of it to Soviet hands! This ruling poured water on every anti-capitalist mill and fuel on the pyre where Morgenthau’s followers sought to torch German industry. Whether General Clay would greenlight this confiscation—making Russians quarter-owners of Krupp in the Ruhr, alongside French and American shares in what had been Britain’s sole domain—remains up in the air. The Control Council, if united, might opt to pass the assets to German states, a “popular” move. But would even socialization-hungry German regional governments welcome such a windfall this way? That’s less certain.

The defense feels duty-bound to fight the Krupp verdict tooth and nail—it offends their every sense of justice. That fight’s an uphill one: Nuremberg special court rulings brook no appeal. Only clemency pleas to General Clay, America’s occupation chief with power to ease sentences, are allowed—yet across nine prior Nuremberg verdicts, he’s never obliged. Krupp’s defenders have filed individual clemency requests and a joint appeal to Clay, clinging to hope that this glaringly unjust ruling might yet be softened. They’ll also exhaust every channel, official or otherwise, to drag the case before a review body—ideally the U.S. Supreme Court—seeking justice, and with it, a fairer reckoning.

Since the Krupp verdict departs on key principles from other trials—like those against Flick and IG Farben—the defense had a legal shot at demanding a plenary ruling from all Nuremberg military tribunals. They filed at once, but to no avail: the chairs of the three active tribunals flatly nixed the plenary session, stunning the defense. The rejection came in mere hours, leaving it a puzzle how the motion’s legal points got any real look.

A lay reader skimming the opening pages of the July 31, 1948, judgment text would surely think Krupp’s deeds warranted stern punishment. “Slave labor” paints a grim tableau—one of systemic abuses, even atrocities! The prosecution’s litany of horrors, embraced and amplified by the verdict, could likely pin such a “system” on half the world’s prisoner or internment camps. With 220,000 Krupp workers amid war’s strain and air raids, abuses happened—isolated ones, not a company-orchestrated regime! The verdict pins the state’s forced-labor scheme on Krupp without qualm, as if they’d eagerly swapped skilled German hands for untrained foreigners, POWs, and prisoners. State production mandates and total war’s realities? The verdict shrugs them off. On “plunder,” even a novice might pause, unversed in defense files, as the verdict wields the Hague Convention of 1907’s quaint norms as World War II’s sole yardstick—blotting out economic warfare, air raids, and post-1945 occupation policies. Only thus could Krupp’s minor “plundering,” dwarfed by the firm’s scale, balloon into “crimes.”

Even a neutral reader can’t miss the verdict’s tone and phrasing—echoes of the prosecution’s own voice. In form alone, it stands apart from the Flick and IG Farben rulings. At times, its hostility verges on venom: an early, dubious prosecution witness likens Alfried Krupp to a “vulture,” while Judge Wilkins, in his biting dissent, dubs the firm an “octopus”!

The defense reeled with bitterness, realizing their Herculean efforts had been for naught. Their mountain of evidence lay ignored—not one exculpatory document or statement made the verdict’s cut. Defense material surfaced only when a damning nugget could be plucked and twisted to the prosecution’s tune. They’d labored to depict Essen’s air-war devastation and its toll on living and working conditions—only for the verdict to note Krupp “exposed” non-German workers to those perils! Time and again, it cited prosecution papers the tribunal itself had ruled inadmissible. Assertions passed as facts; ambiguous options tilted damningly; wording skewed or muddied meaning. “In dubio contra reum” seemed its mantra. The verdict shirked substantiating its findings or tying them to specific defendants—names rarely appeared in its narrative, and then without detail. Here, too, it aped the prosecution: convicting “objectively,” despite twice insisting criminal guilt must be personal! That axiom of civilized law, upheld in Flick and IG Farben, the Krupp verdict honored only in lip service. It gave free rein to the prosecution’s claim that Krupp’s board members were guilty by title, personal fault be damned—leaning on 1937’s Stock Corporation Act and the “Führer principle” from Nazi labor law, as if a 1948 American tribunal should slavishly follow Hitler’s legal playbook.

The asset confiscation leaps out at any observer—a measure unique to this case, where a vast fortune hung in reach. It’s tempting to see this drastic step as the verdict’s glaring flaw. That Krupp’s seizure mirrors Control Council Law No. 9 (the IG Farben precedent) feels tough to dismiss outright.

For the convicted, as this piece opened, the sentences hit extraordinarily hard. Most had languished in custody since 1945, unsure until the trial’s start whether they were held as witnesses or accused. Two years passed before they saw a judge; only at trial’s dawn could they enlist counsel. Investigators coaxed reams of affidavits from them, oblivious that these would later pit them against each other. They could only blunt those statements’ sting by forgoing their own testimony—some took the stand solely to explain their affidavits’ origins, aiming to prove “duress.” Defendant von Bülow spoke of slaps, starvation, shrinking to a “super-Gandhi.” This odd setup—questioning limited to duress—spawned a quasi-trial of the prosecutors, a flip-side to the contempt charges against defenders, sans arrests. The verdict gave no nod to defendants’ character or person—save for Loeser, who faced the People’s Court in 1944 and earned leniency for resistance; the presiding judge even pushed to spare him entirely. Age or illness among the rest? The verdict cared not a whit.

The verdict’s harshness against Alfried Krupp and his eleven co-accused has sparked domestic and foreign outcry. Only communist papers cheered. Krupp’s workers, staff, and pensioners decried it as inhumane. Of the remnant firm’s works councils, just one communist voice beamed approval—chatting in the courtroom gallery, he praised prosecutor Mandellaub as a “good communist” from Essen visits. Essen’s mayor joined the protest, likely not the last heavy hitter to weigh in. Public criticism fuels calls for revision, but more still, the wounded sense of justice among fair-minded folk tips the scales—however silent they stay for now. The very bedrock any regime, even an occupation, relies on feels jolted and uneasy. No Nuremberg verdict has so warped that jurisdiction’s public image; none has so clamored for swift rethinking.

U.S. Senator Robert A. Taft, a top politician and esteemed jurist, told the Republican Party:

“In these Nuremberg Trials, we’ve embraced the Russian show-trial notion. […] Revenge looms over this whole verdict, and revenge is rarely justice. Dressing politics in legal garb risks tainting Europe’s very idea of justice for years.”

Few words could more aptly sum up the Krupp verdict and its fallout.