Source Documents: German Scan

Note(s): None.

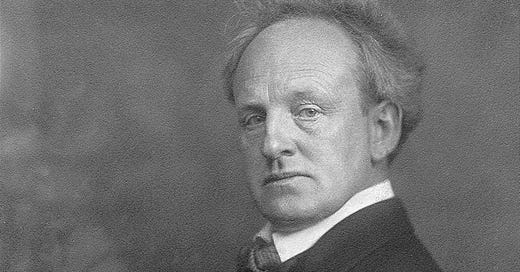

Title: Gerhart Hauptmann on His 85th Birthday [de: Gerhart Hauptmann zu seinem 85. Geburtstage]

Author(s): Willy Wirth

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 1, Issue 6 (November 1947)

Page(s): 360-366

Referenced Documents: None

Gerhart Hauptmann

On His 85th Birthday (November 15, 1862)

By Willy Wirth

It came so close to being otherwise, that Gerhart Hauptmann, the poet who for fifty years stood as the truest voice of our people, might have rejoiced in his 85th birthday. Yet fate, perhaps with a gentler hand than we know, spared him that celebration, releasing him soon after Germany’s collapse from the weight of his personal anguish and the shared bitterness that engulfed his sorely tested nation—above all, his beloved Silesians.

This poet, whose works gave such compelling and poignant voice to compassion for tormented souls as never heard before, must have been shaken to his core by the nameless suffering that swallowed his people. That misery struck his cherished Silesians with a merciless cruelty, born of an enemy stripped of humanity by hatred and vengeance. It is no stretch to believe that this despair helped quench the flicker of life within him. In his final verses, we hear a heart grown weary—disillusionment with mankind’s follies, a cry of accusation, a renunciation of the world, and a yearning for death’s quiet embrace:

„Es gibt kein Siegen noch Unterliegen: Die Menschheit hat Valet gesagt. Es gibt weder Treppensteigen noch Gipfelsteigen. Die Sprache ist ihrer Sprache beraubt. Was Geist auf dieser Erde war, Ist gemordet ganz und gar. Es ist nicht viel, was wir hier sagen, Aber es geht uns an den Kragen."

"There is no triumph, no defeat: Mankind has bid its last farewell. No stairs to climb, no peaks to scale. Speech itself is stripped of words. What spirit once graced this earth Lies wholly slain. Our words here are few, Yet they cost us dear."

And from another poem:

„Ein andrer Sturm weht heut ums Haus Als der vor vielen tausend Jahren: Wir bleiben immer unerfahren Inmitten des Daseins unendlichem Graus. Allein, wir wissen in aller Not Den ewigen Jugendfreund, den Tod."

"A different storm howls round the house today Than roared through countless years gone by: We stand ever untaught, Lost in existence’s boundless dread. Yet in all our woe, we know Death, youth’s eternal friend."

Gerhart Hauptmann came into the world on November 15, 1862, in Obersalzbrunn, Silesia. Like many touched by genius, he was a puzzle to his family in his youth. For such extraordinary souls often sense, in their early years, a rich wellspring of talents and possibilities within—none of which they wish to cast aside. An inner, unspoken urge resists binding them too soon to one path. Their brilliance demands they wander through diverse pursuits and studies, heedless of practical ends, gathering the breadth of experience and depth of spirit essential to a great creator. Thus, they are often misread as unsteady or wavering, deemed indecisive, while their simpler peers—less burdened by complexity, more direct in aim, born to climb straight paths—settle early into trades that suit them, their growth complete.

So it was that young Gerhart was sent to his uncle’s estate to train as a farmer, but every effort to kindle in him a passion for that life fell flat. He could not see it as his calling. At last, he won his way to the art school in Breslau. There, his work with sculpture honed an inborn gift for seeing the physical world keenly. Though he soon left that craft behind, the power to bring the figures of his writings to life with vivid, tangible presence endured as the lasting fruit of those days.

Already, Hauptmann felt the pull toward poetic creation, and even in Breslau, his first ventures into this realm took shape. Later, in Jena, he plunged into scientific and philosophical studies, yet a deeper drive urged him to grasp life and the world in their widest sweep. This led him on a journey across the Mediterranean. It was not the echoes of ancient culture that seized him most; rather, a profound social pity for the poor of Spain and Italy gripped his soul. He listened with an open heart to the raw language of want, baffled that some, cushioned by privilege, could romanticize such ragged poverty.

For a time, he even toyed with becoming an actor, taking lessons from Alexander Heßler, a quirky former director of the Strasbourg City Theater. That chapter later bloomed into the wry charm of his tragicomedy The Rats. His dramatic studies also bore fruit when he staged Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell in a bold new vision, casting the masses as the true pulse of the action in a naturalistic vein—an approach that stunned audiences with its force.

New works began to flow, brimming with a keenly felt compassion for the downtrodden, their form and substance sparked by Arno Holz’s Book of the Time, the cornerstone of German naturalism. Hauptmann’s heart bled sincerely for every sorrow, longing to lift every burden, yet he was never a partisan socialist—political dogma, with its narrow slant, stood apart from his essence. A friend from his youth once swore he’d never known a soul in whom social feeling ran so deep, woven into the very fiber of flesh, blood, and nerve, as it did in the young Gerhart Hauptmann.

In his wrestle with the world he knew, and his search for the right vessel to hold it, his meeting with Arno Holz proved a turning point. In Holz’s unflinching naturalism, he found the form that matched his vision. His first naturalistic work, the novella Bahnwärter Thiel, stands as a testament to his arresting craft—capturing the human spirit ensnared by the relentless pull of its surroundings.

Then came the Free Stage, a fledgling society dedicated to modern dramatic poetry, which chose Hauptmann’s play Before Sunrise as its second offering after Ibsen’s Ghosts. Overnight, this near-unknown poet became a beacon for a young generation of writers who hailed him with fervor, while traditionalists hurled their fiercest scorn. In swift succession through the 1890s, a series of dramas emerged—joined later by kindred works and neo-romantic pieces from his final years—that will likely secure Gerhart Hauptmann’s place forever among the titans of world theater. Foremost among them: The Weavers, perhaps not the zenith of his art but surely his most famed and defining work; The Beaver Coat, a rare gem among great German comedies; Fuhrmann Henschel, where naturalistic drama reaches its peak, breaking its own bounds to rise through a soul-deep warmth and strength into a realm of timeless human truth; and on that same plane, steeped in the heartfelt humanity that echoes so rarely across the poetry of any age or tongue, stand Rose Bernd, Michael Kramer, Gabriel Schilling’s Flight, The Rats, and from his later years, Before Sunset—the play that inspired the Jannings film The Ruler.

Among these creations, rooted in a naturalistic view of life, Florian Geyer speaks most powerfully to us as Germans, a towering symbol of our tragic national fate—Hauptmann’s own cherished child among his works. Here, the shattering of the Peasants’ War’s grand hopes unfolds in scenes of gripping, spellbinding stagecraft. Florian Geyer’s noblest dreams—a united, mighty German empire—crumble against the stubborn folly of peasant minds and the selfish blindness of the nation’s leaders, from which springs the choking weed of German discord.

What The Weavers painted of its own time, this drama sought to mirror for the vast sweep of the Peasants’ War. A full portrait of the German people around 1525 was his aim, bringing every class and faction to life. Hauptmann dove into meticulous study, traveling to the landscapes of his tale—especially Franconia—immersing himself in the language of the 16th century until its cadence was his own, and weaving it into his work. He wrestled a mountain of material into a prelude and five acts, choosing not to chart the movement’s birth but its downward arc—a thread that runs through so many of his plays.

Florian Geyer is no hero of old. Hauptmann mused in his Ausblicke notes: those who clamor loudest for a hero would curse him loudest if he came. True heroism, he wrote, may lie in a soul’s richness, a quiet, vast feeling—and so Geyer is. His heart blazes for justice; the finest of the peasant cause, the fight for all to be free, lives in him. A plain, honest man, he suffers greatly, as Hauptmann’s figures often do. Each act follows a pattern: a chaotic chorus of voices fills the first half, then a pause—and into that tangle steps Geyer, bearer of the purest ideal, striking a clear, resounding note. Every soul in this play, not just the leads but the smallest parts, pulses with raw, vivid life.

Hauptmann had high hopes for its impact, and rightly so. Yet in January 1896, audiences faltered before this towering work; eight years later, a revised staging met the same cold incomprehension. But after the collapse of 1918, Florian Geyer swept across Germany’s great stages. Crushed by recent ruin, people grasped its form and meaning at last. Here was not just the Peasants’ War’s tragedy, but Germany’s—a timeless emblem of our recurring fate. Even now, to read it is to be shaken by its stark echo of our latest trials; a performance today would pierce us deeper still, lodging in our very core.

Less tied to the primal root of his naturalistic vision are the neo-romantic, neo-classical, and symbolist plays of his later years. These spring more from his learned encounters than his raw experience. Yet even here, his shaping genius shines, crafting works of striking originality that bathe old myths in fresh light and draw them close to our hearts anew. Among them: Poor Henry, The Bow of Odysseus, Winter Ballad, Indipohdi, Hamlet in Wittenberg, and more—many, especially the first two, adorned with a linguistic beauty rivaling Stefan George’s finest verses. In these debated works, Hauptmann foreshadows strains of expressionism and its aftermath.

Among all dramatists of note, Gerhart Hauptmann, as many voices agree, stands nearest to William Shakespeare, the world’s supreme stage poet, in the art of crafting living characters. For both, words are but stage directions of another kind; their figures speak only what flows naturally into gesture and deed, what the body can play. The magic of dramatic language lies in its power to bridge the soul’s stirrings into visible motion. Take that moment in Florian Geyer when peasant leaders drive their daggers into a chalk circle Geyer traces on a door, naming each thrust’s target, yet faltering with the words, “into the heart of German discord.” That is true dramatic style—language wielded so it leaps into flesh and action. Thus, a play by a born dramatist demands the stage to fulfill its destiny; mere reading dims its fire beside the works of oratorical poets like Schiller or Ibsen, which grip us on the page but can stifle an actor’s craft in performance, leaving them reciting rather than embodying. Every actor knows the joy of playing Shakespeare or Hauptmann, while Schiller and Ibsen pose knotty, often unsolvable challenges. To read Hauptmann’s plays without this in mind risks disappointment; but see them after reading, even in modest staging, and they soar beyond all hope.

Where man must bear the action, any false note jars. It is harder to show people fully alive in motion than to set motion flowing through them, as a tale does. A fine storyteller needs a sharp eye for the world; insight and empathy suffice to recount human struggle, but to shape it for the stage, they fall short. A dramatic figure demands the poet carry within all that will become speech and soul’s gesture. A historian can sketch Caesar from without; a dramatist must have Caesar’s spark to summon him. A boundless, varied life makes the dramatist. As an unfelt emotion rings hollow, so an unlived being cannot speak true. This is why, for every hundred gifted tellers, one original dramatist is rare—why poets secretly crave drama’s crown, why we exalt Shakespeare as humanity’s peak.

Gerhart Hauptmann held a vision and inner grasp of the world matched only by Shakespeare before him—a mighty claim. If he falls short of that pinnacle, it is because his stance toward life’s riddles lacks the breadth and vigor of his sight, missing a spirit’s dynamism to rival it.

Drama, unless it seeks only to amuse, is a mirror of life’s meaning. By its nature and birth, it must summon eternal forces—call them gods, laws, or ideals—through human striving, suffering, and clash. A mark of this cosmic reach, oft misused or misread, is true verse: not a metrical toy or rhetorical flourish, but the soul’s unbidden echo of the world’s pulse. Only in verse does the mystery and law of existence speak its poetic truth directly. Herder saw this, naming poetry humanity’s first tongue, a truth borne out by ancient words. Yet verse is not nobler than noble prose by birthright; still, a poetic cosmos without rhythm’s binding form—mirroring life’s elemental sway—is unthinkable.

But, one might ask, did Hauptmann not write his greatest plays in prose—does this not clash? Not so. Read his dramas with care, attuned to their sound, and from The Weavers onward, a distinct rhythm hums through. His prose melts easily into free cadences with a gait all their own—the rhythm of Hauptmann’s worldview, from which his characters rise and into which they are bound. Consider these lines, plucked from two prose plays, laid bare in their flow:

From Florian Geyer:

Der heimliche Kaiser muß weiter schlafen. Die Raben sammeln sich wieder zu Haufen. Zu Ostern entstieg der Heiland dem Grabe. Zu Pfingsten schlägt man ihn wieder ans Kreuz.

The secret emperor must sleep on. The ravens gather again in flocks. At Easter, the Savior rose from the grave. At Pentecost, they nail him to the cross again.

From Michael Kramer:

Hören Sie, der Tod ist verleumdet worden, das ist der ärgste Betrug in der Welt! Der Tod ist die mildeste Form des Lebens; der ewigen Liebe Meisterstück.

I tell you that death has been maligned. That is the worst imposture in the world. Death is the mildest form of life: the masterpiece of the Eternal Love.

This is the “Gerhart Hauptmann tune.” On it rests the mood and meaning of his dramas—a falling rhythm, perfectly tuned to his pity and social soul.

Gerhart Hauptmann also achieved greatness as an epic writer. His Emanuel Quint is a tapestry woven with questions and answers, steeped in potent atmosphere, tender lyricism, and gripping drama, brimming with the vigor of portrayal and the depths of humanity. Among his varied novels and tales—not all of equal merit—one shines as the zenith not only of Hauptmann’s craft but of German storytelling itself: The Heretic of Soana, unveiled to the world in 1918. It astonishes with the blaze and fervor with which this aging, silver-haired poet chants his exultant hymn to love. Above all, it is the masterful restraint and shaping of its beautiful, enthralling substance—imbued with an almost classical vision, a lofty yet earnest and unmocking serenity—that grants this tale of a strange heretic and seeker of the divine its dignity and enduring strength. The mythic inheritance of humankind hums through its every line, yet never does the narrative drift into the vague, the misty, or the unshaped. The primal pulse of Pan stirs in man and beast, in tree and stone; its force needs no symbolic unveiling, for within the characters themselves the ancient powers of Eros, Pan, and Dionysus dance their wild dance. The deepest truths lie unspoken, yet they are ensnared within this poetry—set in modern days, yet piercing through to the ultimate essence of humanity and the mythic wellsprings of life. What Hauptmann’s radiant travelogue Greek Spring, born of a sojourn through Greece, heralds as the prize of life’s triumph, the glory of those robust in body and soul—a theme that, in the poet’s growth, rang like a fresh mustering of all his powers at the dawn of the twentieth century’s first decade—blossomed a decade later into the captivating form of The Heretic of Soana. For Hauptmann, all love, when true, is ever one and the same. In his Poor Henry, we find the words:

„Was himmlisch schien, ist himmlisch, und die Liebe bleibt — himmlisch, irdisch — immer eine nur.“

“What seemed heavenly is indeed heavenly, and love remains—be it celestial or earthly—ever one alone.”

Thus, in The Heretic of Soana, a young Catholic priest awakens to true heavenly love through the raw, sensual passion for a radiant girl, alive with the freshness of a nature-bound existence, who surrenders herself willingly to him. Only then do the marvels of nature’s grandeur and art’s splendor unveil themselves to his soul. Nietzsche would have reveled in the sheer delight of this creation.

Gerhart Hauptmann’s true significance for Naturalism lies in how his innate disposition harmonized with the core strivings of his era at pivotal moments. The young Hauptmann was one of those blessed creators who, by following the whisper of their inner voice, fulfilled the deepest yearnings and will of their generation. A poet’s resonance with his time hinges always on whether his primal nature aligns with the intellectual currents that sweep through his age.

His essential character might be described as a fusion of instinctual yet finely attuned sensuality with a pensive plunge into the realms of pure spirit. Hauptmann possessed an unparalleled gift for entering the hearts of simple, soulful folk, paired with a near-miraculous talent for rendering vivid portraits of humanity and its surroundings—atmosphere, nature—merging into tree and cloud, sea and peak, and above all, into people, insofar as they are nature itself: passion, instinct, and soul. The era’s dreams of social reform echoed within him too. Yet, unlike Zola or Ibsen, his social ethos sprang not from reasoned insight, calculated thought, or a thirst for justice, but from a raw, primal outpouring of a anguished spirit. He cared little for dissecting the flaws of society’s structure or dreaming up a utopian “Third Realm” of righteousness. Instead, he was seized by the plight of the lone, suffering individual, their fate a call to awaken pity for each mourning, tormented being. His profound compassion for all that breathes flowed from a oneness with all existence, drawing him to the weak, the helpless, the broken—casting his lot with the downtrodden and the pained. The affliction of his most finely drawn figures arises less from man-made outer conditions than from an inner destiny rooted in human nature itself, a cosmic thread no shift of state or social order can unravel.

„A jeder Mensch hat halt 'ne Sehnsucht“

“Every person has their longing,”

says old Hornig, the rag collector in The Weavers, and this soulful note—so achingly tender in all Hauptmann’s characters—is the eternal, unquenchable surge of the human heart, the ceaseless fount of all its bliss and all its woe.

When the poet dwells in the intimate sphere of his youth—his earliest impressions, his native dialect, his first encounters—his characters gain an eerie transparency and vibrant truth. Each bursts with life, a singular soul with their own timbre, their own feelings and words. Every work, in its way, is a classic—a perfected shape, however humble its intellectual core.

The Nobel Prize in Literature, bestowed upon him in 1912, crowned his outward significance to the cultural tapestry of his time and kin. His own words—

„Man senkt nicht, wie Taine zu glauben scheint, als Künstler die Wurzel in eine Zeit. Man senkt sie ins Ewige und ringt sich vielleicht empor an der Zeit“

“An artist does not, as Taine supposes, root themselves in an age; they root themselves in the eternal, perhaps wrestling upward through the age”

—prove that even in his most naturalistic works, this poet was ever more than a mere Naturalist. From a voice of the 1860s generation, he rose to a herald for an entire epoch, and with Florian Geyer, for his people and their fate. The noblest part of our soul, the richness of our feeling, finds matchless form in the deep, heartfelt resonance of his figures.

Once more, the boundless agony of a war waged with inhuman cruelty shook the aged poet to his marrow. He endured the ghastly night that razed Dresden, and dread consumed him. The weight of such suffering and ruin overwhelmed a frame already frail with sickness. Yearning to perish in his homeland’s heart and bear its doom alongside it, he lingered his final months at his Silesian haven, Wiesenstein in Agnetendorf. There, though untouched by the enemy occupiers and met with fitting reverence, he bore unspeakable grief for his uprooted countrymen, cast out from hearth and home. Bound to his sickbed, he longed to craft a grand address to the German people, to kindle courage in their bleakest hour, but his strength faltered. On Thursday, June 6, 1946, his eyes closed forever. As he wished, his body was clad in a Franciscan robe, his head resting in the coffin upon a copy of his poem The Great Dream. A special train, granted by Soviet hands, bore him first to Berlin, then to Hiddensee—that small isle, his summer sanctuary for years. There, amid the quiet fisherfolk he knew by name, he slumbers eternally in the lone village churchyard, the patriarch of German poets in our time.

The cataclysmic events and unheard-of trials of his last year he could no longer bind into a work to unveil their timeless meaning or proclaim their solace. Yet Prospero’s final words from his drama Indipohdi ring as a prophetic echo of what befell us and him in his waning hours—a testament, a balm for the seemingly hopeless tangle and desolate wandering of humanity in our days:

Noch einmal in dem heiligen Augenblick

des Abschieds, wo der mächtige Webstuhl noch

dröhnt und mein Werk erschafft, was doch nicht

mein ist,

grüß ich dich, furchtbar-wundervolle Welt

des Zaubers und der Täuschung. Du gebierst

millionenfachen Fluch, wie Blumen auf

glückseligen Wiesen, und ich habe sie

jauchzend gepflückt und jubelnd mich gewälzt

im Schmerzenstau, im Todesduft der Gräser.

Und als mein immer wachsendes Geweb

mich enger stets umstrickte und Gestalt,

unzähliger Form, mich, der sie schuf, umdrang,

da würgte mich mein eigner Zauber, drang

mein Volk von Schatten grausam auf mich ein

und legte mich, den Schöpfer, in die Folter.

Ich schlage um mich. Kampf, noch immer Kampf,

als hab ein Wutbiß diese Welt gezeugt,

und diese blutige Riesenmühle, Schöpfung,

die grausam mörderisch die Frucht zermalmt.

Nein, nein, es ist nicht wahr. Nichts ist hier

Täuschung,

denn Blut ist Blut und Brot ist Brot und Mord

ist Mord. Sind alle diese Rachen,

die Mitgeschöpfe gen einander gähnen,

womit dies blinde Leben schrecklich prunkt,

Täuschung? Zerstückt des Haies Kiefer nicht

des Menschen Leib? Ist nicht des Tigers Hunger

qualvoller Haß und Mordsucht, und zerreißt

er nicht Lebendiges und schlingt sein Fleisch?

Ward eine Kreatur in diese Welt

hineingeboren ohne Waffe, und

die Mutter, die in Furcht und Grau'n gebiert,

gebiert sie Furcht und Grauen nicht im Kinde? -

Das ist nicht Täuschung, nein, es ist so, und

so wäre denn dies Täuschung, daß die Welt

nur meines Zaubers Täuschung war; und dies

ist Wahnwitz! — Nein! Zwei Augen leuchten mir

im Nebel. O, Tehura! Und es dringt

wie leise Sphärenklänge auf mich ein,

vom Stern der Liebe. Nah ist die Versöhnung.

O, reine Priesterin, nimm weg die Welt

und schenke mir das Nichts, das mir gebührt.

Ich fühle dich, ich sinke in dich! Nichts!Once more at the sacred instant of departure where the mighty loom still thunders and my work creates what yet can never be mine, I hail you, terrible-wondrous world of spells and delusion. You birth curses countless as meadow flowers in blissful fields—and I have plucked them laughing, rolled exultant in anguish's dew, in grasses' deathly musk. When my ever-swelling weave enmeshed me tighter—forms innumerable pressed round their maker—my own magic choked me. My shadow-children rose to rack their creator's flesh. I strike wildly. Struggle—still struggle—as if fury's bite conceived this world, this bloody mill of Creation that grinds life's fruit to murderous pulp. No—no illusion. Here's truth: Blood stays blood, bread stays bread, murder stays murder. These maws that gape at kin—with which blind Life parades its horror—are these deception? Does the shark's jaw not shred man's flesh? Is tiger-hunger not pain-steeped hate— that rends warm meat from screaming prey? Was any creature born unarmed into this night? The mother birthing through fear and dread—does she not birth that same fear in her child? This is no trick. Thus if deception lives here, let it be this: that all existence was but my magic's fleeting dream. And this—madness! No! Two eyes pierce the fog. O Tehura! Now sphere-music whispers from love's star. Reconciliation nears. Pure priestess—take this world away, grant me the Void I've earned. I feel you—sink—dissolve! Nothing!

Many strive to be the sun. They may dazzle as she does, yet cannot warm as she does. Others hoard, distrusting all that is light within themselves. They renounce the air -that mobile element which once shielded them - becoming dead moons frozen in the void's chill, barren the stones of their mountains. Ah, those who dwell on earth are not, alas, one earth alone. With feet planted - unshifting Pole; and Pole too the head, constant as Arctic ice -thought's chill and midnight sun that never sets. But scorching at the heart, Equator, circling with mighty sweep! Fury and thunder gird it with forests, Life runs riot. Thus you are Axis, around which a world revolves.