Title: Diplomatic Game [de: Diplomatenspiel]

Author(s): M. v. Engelhardt

Issue: Year 01, Issue 04 (September 1947)

Page(s): 241-243

Dan Rouse’s Note(s):

Der Weg - El Sendero is a German and Spanish language magazine published by Dürer-Verlag in Buenos-Aires, Argentina by Germans with connections to the defeated Third Reich.

Der Weg ran monthly issues from 1947 to 1957, with official sanction from Juan Perón’s Government until his overthrow in September 1955.

Source Document(s):

[LINK] Scans of 1947 Der Weg Issues (archive.org)

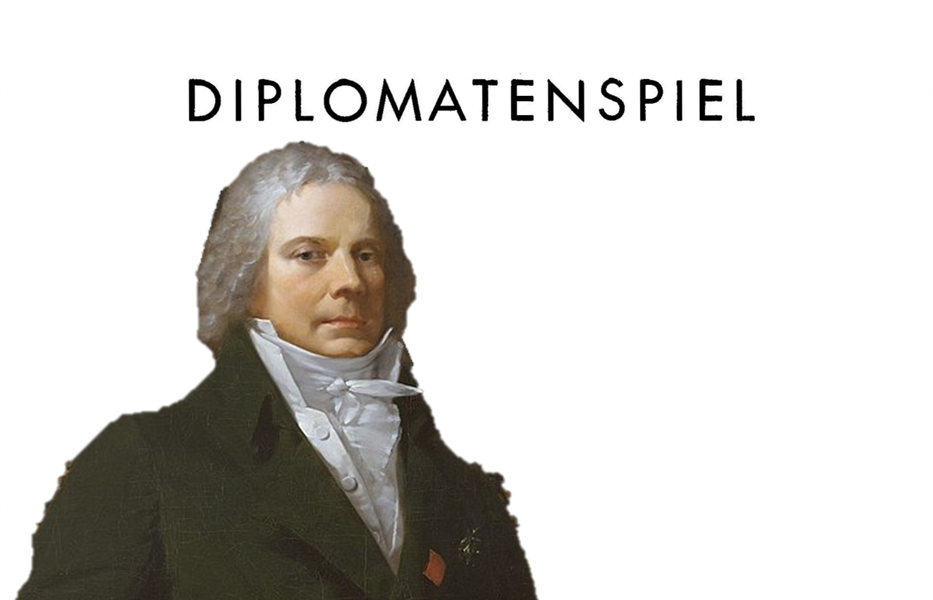

Diplomatic Game

Short Story by M. v. Engelhardt

In the 1830s, Prince Talleyrand served as France’s ambassador in London. Within a chamber adorned with all the opulence of that age, the prince sat at his desk, immersed in composing a memorandum to his government.

The Belgian revolt against the King of the Netherlands posed no small quandary for the diplomats of the great powers. At that moment, a conference convened in London to seek a peaceful resolution to the Belgian Question, a matter of particular concern to England. English diplomacy grew anxious, for Prince Leopold of Coburg, newly chosen as King of the Belgians, had sought the hand of King Louis Philippe of France’s daughter. London feared this union would bolster French influence and looked to Prussia and Russia for aid in thwarting the marriage scheme. In his memorandum, however, Talleyrand urged his government to uphold the plan, asserting that England, by his intelligence, could not rely on the support of the central powers.

A gentle knock broke Talleyrand’s concentration, and Embassy Counselor Bertin entered the room with a deep bow.

“What tidings do you bring, my dear Bertin?” inquired Prince Talleyrand, ever gracious to those beneath him.

“Your Excellency dispatched me yesterday to the English Foreign Office to have several passports stamped,” Bertin replied. “The official I dealt with informed me that his superior, Lord Seymour, desired a word with me.”

“Lord Seymour?” Talleyrand echoed. “Is he not the right hand of Viscount Palmerston?”

“Indeed, Your Excellency,” Bertin affirmed. “Lord Seymour received me alone. After a few empty pleasantries, he extended a peculiar offer: to deliver to him copies of all the letters Your Excellency has sent to the ministers of Prussia and Russia these past weeks, along with their replies. He proposed 200 pounds for each letter.”

“What a careless way to squander coin!” Talleyrand exclaimed. “And how did you respond?”

“I must confess, Your Excellency, that this audacious proposal left me utterly astonished at first,” Bertin admitted. “Then I resolved not to give Lord Seymour a firm answer on the spot and requested leave to consider the matter. He consented.” When Talleyrand offered no immediate reply, Bertin ventured further: “Would it not be fitting to expose this affair to the public and stir an outcry in the press?”

“My dear Bertin, you too are a diplomat and ought to know that a true statesman never raises a clamor—save to cloak his own defeat,” Talleyrand countered with a faint, knowing smile. “Tell me, though, why do you shrink from Lord Seymour’s suggestion?”

Bertin gazed at the prince in profound disbelief. “Do you mean to say, Your Excellency…” he faltered, “that I should sell the copies?”

“Of course I mean precisely that, my dear,” Talleyrand replied. “Return to me tomorrow at this same hour. I shall be out, but my study and the right drawer of my desk will remain unlocked. There you will find five letters. Take them, prepare five copies, and present them to Lord Seymour the day after. For each, you shall receive 200 pounds—a total of 1,000 pounds. After all, your wedding approaches, does it not?”

“But Your Excellency,” Bertin protested, “this is a crime! I have served the French embassy for a decade and would not have my honor tainted by suspicions of bribery!”

“Be at ease, Bertin,” Talleyrand soothed. “I shoulder all responsibility and its consequences. Men like Lord Seymour can only be bested with their own stratagems.”

Talleyrand resumed his writing. Bertin bowed once more and departed the chamber.

Having completed his memorandum, Talleyrand gathered several blank sheets, fastened them together, and inscribed in his clear hand upon the first page: “Secret Correspondence between the Ambassador of France, Prince Talleyrand, and the Royal Prussian Minister, Count von Arnim.” On the next, he drafted a letter ostensibly penned by Count von Arnim to himself, wherein the Prussian minister lambasted French policy with biting severity. Talleyrand then crafted his own response to Arnim, sharper still in its rebuke. A second missive from Arnim followed, its tone so belligerent as to be unthinkable for a diplomat.

When the five letters were complete, the prince placed them in the right drawer he had described to Bertin.

Days later, after Bertin confirmed that the affair with Lord Seymour had unfolded as intended and that he held the 1,000 pounds, Talleyrand summoned his private secretary, Count Couronelle.

“My dear Count,” Talleyrand began, “you too have received an invitation from Lord and Lady Seymour to Marlinghouse. Naturally, we shall attend together, and I have a discreet task for you tied to this occasion.”

And so the prince recounted the tale of Bertin and Seymour, imparting specific instructions for Marlinghouse.

At Marlinghouse, Lord Seymour’s summer estate, a dazzling assembly of guests had gathered. Prince Talleyrand was greeted with uncommon warmth by Lord and Lady Seymour. That evening, the two diplomats strolled through the splendid park of the residence.

“Tell me plainly, my dear Prince, as friends do,” Lord Seymour pressed, “how stand your relations with Prussia now?”

“With Prussia?” Talleyrand repeated, his voice tinged with innocence. “Oh, they are quite splendid.”

“Are you in earnest?” Seymour asked.

“Entirely so, my Lord,” the prince assured him. “Since King Louis Philippe’s ascent to the throne, our ties with Prussia, Russia, and Austria have never been so fine as they are today.”

Lord Seymour nodded with smug satisfaction, and Talleyrand chose not to dim his cheer. The Englishman seemed convinced he had peered into Talleyrand’s hand and now sought to press his perceived advantage.

“We shall not permit your princess to wed the King of the Belgians,” Seymour declared. “I know your exchanges with Prussia well enough. War with the Holy Alliance looms over you!”

“We shall see who has the last laugh,” Talleyrand mused silently. To shift the conversation, the French diplomat began to praise the park’s exquisite beauty.

At the banquet, Prince Talleyrand and Count Couronelle were granted seats of honor beside their hosts.

Lady Seymour embodied graciousness itself. After the meal, the gentlemen lingered in the dining room over coffee and liqueur. Following his instructions, Count Couronelle deftly guided the discourse as planned. With finesse, he turned the talk to literature, a topic Lord Seymour eagerly embraced, delighting in flaunting his erudition.

“Do you not agree, my Lord,” Couronelle ventured, “that a writer’s genius can never align with the practical duties of an official?”

Lord Seymour demurred, insisting he knew numerous instances where those who excelled in state service also shone as literary talents.

“Oh, my Lord,” Talleyrand interjected, as if by happenstance, “I must side wholly with you and differ with our dear Couronelle. You all know me well—I am rooted firmly in the practical world. Yet I have let my imagination roam free and even committed some fancies to paper.”

A ripple of amazement stirred the room.

“Works by Prince Talleyrand!” Lord Seymour cried. “This is a revelation—Prince Talleyrand, an author!”

The prince smiled with quiet humility. “Were I not wary of disappointing so discerning a judge as Lord Seymour and these gentlemen, I should like to share a modest diplomatic creation I penned not long ago.”

The company unanimously entreated the prince to present his latest work.

“I shall fetch the manuscript from my room at once,” Talleyrand replied, rising. “Alas, I am a wretched reader and would humbly ask you, my Lord, to recite this little whimsy to our guests.”

Lord Seymour readily agreed. While Talleyrand retrieved the document, footmen arranged a small table with two candles, and the guests positioned their chairs to view the speaker with ease.

Within minutes, Prince Talleyrand returned and handed the manuscript to Seymour. The lord settled at the table, unfolded the pages, and read aloud: “Secret Correspondence between the Ambassador of France, Prince Talleyrand, and the Royal Prussian Minister, Count von Arnim.” Abruptly, Lord Seymour fell silent. Pale and shaken, he slumped back in his chair. The guests sat hushed, bewildered by the turn of events.

“My Lord, why do you not read on?” Talleyrand inquired, his tone all courtesy.

“Prince, you have mastered the art of retribution,” Seymour replied, then withdrew from the gathering. Talleyrand reclaimed his manuscript, bade farewell to Lady Seymour and the company, and departed for London that very night.

Lord Seymour had little choice but to confess to his guests the following day how he had bungled an attempt to bribe Talleyrand’s counselor, Monsieur Bertin.

“Indeed,” the lord admitted, “Prince Talleyrand secured a dazzling triumph over me yesterday. What’s more, I received this letter from him: ‘My Lord! To you, my dearest friend, I hasten to report first that the wedding of our princess to the King of the Belgians occurred last Wednesday. Our mutual friend Bertin, too, has just wed. He always believed he could sustain a family, and now, having tapped a fresh vein of diplomatic revenue, he is utterly certain of it. Your devoted Talleyrand.’”