Franz Schubert, on the occasion of his 150th Birthday [Y1-I5]

Franz Schubert, im Jahre seines 150. Geburtstages

Source Documents: German Scan

Note(s): None.

Title: Franz Schubert, on the occasion of his 150th Birthday [de: Franz Schubert, im Jahre seines 150. Geburtstages]

Author(s): Ernst Aufrecht

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 1, Issue 5 (October 1947)

Page(s): 284-290

Referenced Documents: None.

Franz Schubert, on the occasion of his 150th Birthday (January 31, 1797)

By Ernst Aufrecht

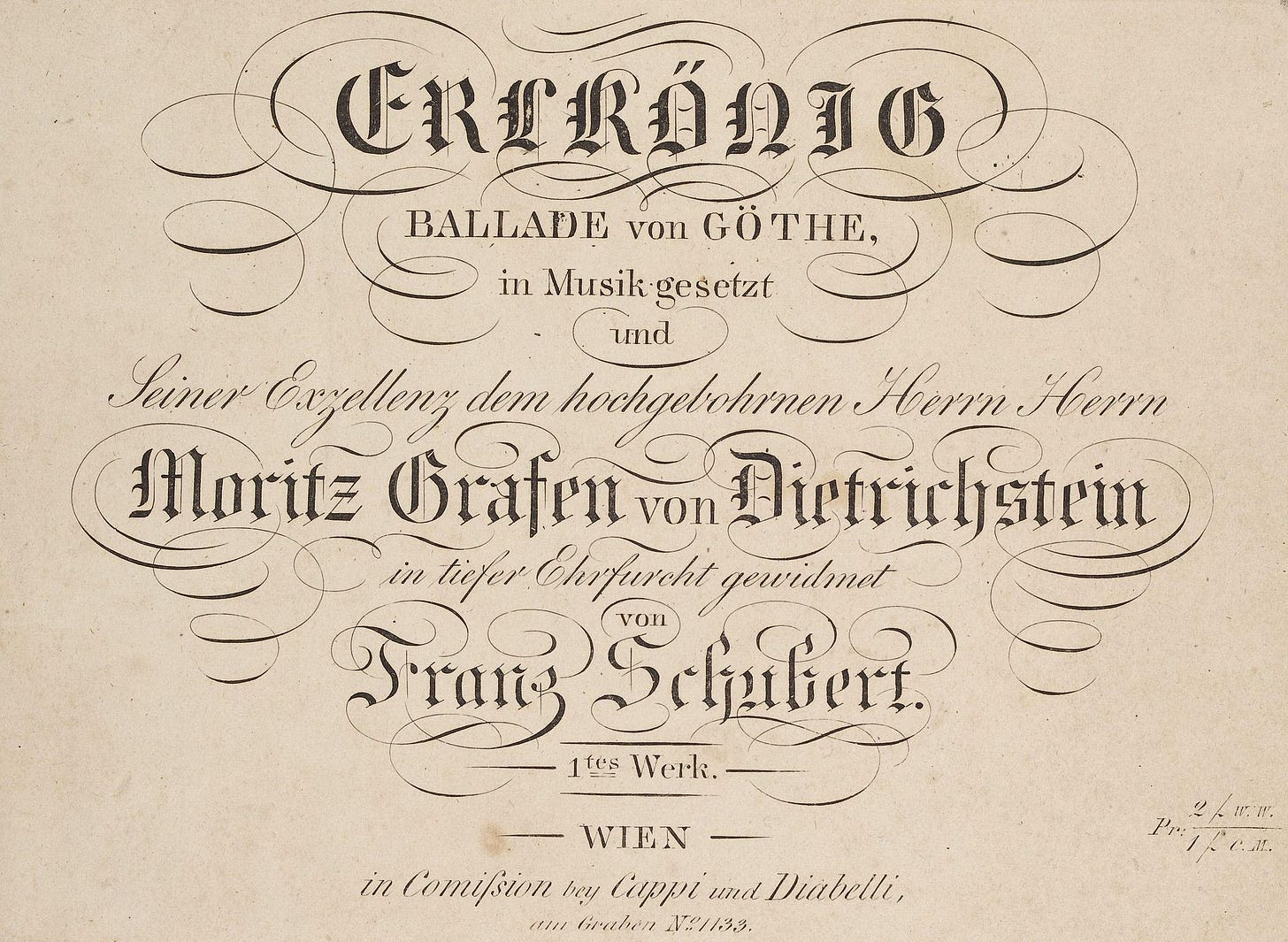

Schubert — a life cut short, a blossoming and a fading, a romantic dreamer. Outwardly, a sweet abandon; inwardly, already the cruelty of modern turmoil — all this resonates in his name. Each year on November 19th, we commemorate the tragic end that came far too soon. At the mention of Schubert, we recall the spectral yet gentle and soft voice of death approaching the maiden in the blooming meadow. We think of his circle of friends: Schober, Vogl, Schwind, Mayrhofer, Hüttenbrenner, Bauernfeld, Grillparzer; of cheerful wine-filled evenings, of nights of Dionysian rapture. But only upon closer examination of Schubert’s life circumstances do we sense how his creative drive obeyed an invisible, iron law, how this young life, as if predestined, had to wither swiftly, and how it scattered all its immortal works under the relentless whip of life’s haste. We feel that Schubert’s unprecedented productivity (the “Erlkönig” was composed at the age of 18 in just a few hours one afternoon) can only be explained by a dark premonition of an early demise. Already embodying the mood of the Vormärz with the pace of life of our own time, his early Romanticism, in indescribable freshness and colorful splendor, was not meant for the era to which his life was bound, but for the future. Schumann, Wagner, Liszt, Richard Strauss, and many more names up to the latest New Romanticism — do they not all stand in the shadow of the unassuming schoolmaster from Lichtenthal?

And another feeling stirs within us at the name Schubert: a deeply shameful one. Was it possible that no honorable publisher could be found for his songs, chamber music, symphonies, and masses, that a genius simply had to subsist on the hospitality of others or the sporadic proceeds of his compositions? Unbelievable, how destitute the thirty-one-year-old died. In his estate, nothing was found but a few clothes and household items — no money, no tangible object of “value” save his scores, which held a different, spiritual worth. Unreconcilably stark stands the Schubert enthusiasm of our century and of today’s impoverished Vienna against the neglect he endured from the then-rich, world-powerful, sensually joyful Vienna. And beside the shame over his contemporaries’ incomprehension stands another, more recent disgrace, the most scandalous case of capitalist exploitation of an author: the Das Dreimäderlhaus affair, the Schubert big business, through which the Viennese operetta librettist H. Berté turned Schubert’s heartfelt melodies into a commercial triumph, reaping box-office successes at the expense of the departed.

Schubert’s Romanticism would not possess such primal freshness today if it had merely mirrored the zeitgeist of the Vormärz. It bears kinship with the Classical, yet it reaches far, far beyond the spirit of its time. Schubert’s realism carries the hallmark of Goethean completion and finality of form. We know how many letters of admiration Schubert sent to the Weimar privy councillor, Goethe, without ever receiving the slightest token of gratitude or acknowledgment. We know how many of Goethe’s texts he endowed with musical immortality. That which still tied him to the classical current of German art, even to Beethoven — who only encountered a few of Schubert’s songs on his deathbed — was, however, infused with soul in an entirely different way: not with “real” sensual delight, but with that drive for Dionysian zest for life, which pours forth from Schubert’s creations like a roaring, inexhaustible stream of light and sun. The entire landscape around Vienna, the summer of Upper Austria, has been transformed into sound. The Trout Quintet, the String Quintet in C Major, the magnificent Great C Major Symphony are delicate or powerfully flaring sheaves of light, radiating Dionysian joy in the world.

But the distinctly “modern” quality of Schubert, much like Beethoven, lies not merely in the technical means of expression, nor in his harmonies — bold for their time — which, at least in the final phase of his life, remained incomprehensible even to his closest friends. The connections here, as with Mozart or Beethoven, are sociological, not purely musical in nature. Mozart’s audience was the high nobility of Bohemia, Vienna, and Hungary. Beethoven’s audience, in the symphonies of his maturity and the monumental works of his late period, was no longer this nobility, but the third estate — the bourgeoisie, emancipated by the Wars of Liberation. Schubert’s audience was already the universe of all humanity. He was the first truly democratic musician from the outset. Rising from the depths of the people, he sang again to the depths of humankind, though his sentiment and the wondrously noble form of his musical language gripped and inwardly fulfilled this new audience only later.

Schubert heiß ich, Schubert bin ich, Mag nicht hindern, kann nicht laden. Geht ihr gern auf meinen Pfaden, Nun wohlan, so folget mit!

"Schubert I am called, Schubert I am, I’d not impede, nor can I summon. If you’d gladly walk my pathways, Come now, then, and follow on!"

Thus sang Grillparzer. Schubert invited no one to feast at his table, nor did he wish to bar anyone’s way; rather, he was the very freshness and beauty of nature itself—no rebel, no troubling soul, no free spirit, and by no means a partisan artist. He let beauty bloom for beauty’s own sake, and those who gazed upon it were blessed.

Yet in one regard, Schubert, as a musician and the true "classicist of Romanticism," stands sharply apart from all that came before him. Here, once more, a Goethean trait shines through. All that he transforms into sounding life, into artistic expression, ceases to be a mere symbol or abstraction of reality—it remains reality itself. Schubert’s music is not solely a world of subjective feeling; it draws the outer object so deeply within that one might call it "sounding vision." Every sound of nature, every stirring of the human heart, the life of the tangible world around us, and the voices of the spirit realm spring forth at once; whatever moves finds voice in sound. For the first time in music, at least on such a vast scale, the contemplation of nature floods all that one soul can scatter abroad in feeling. Who has captured the grace and swiftness of a trout’s motion so precisely, yet so beautifully, as Schubert in the accompaniment to his song "Die Forelle"? The somber bass triplets of "Erlkönig" paint not just a mood but the very motion—the strike of the horse’s hooves, the rider’s rhythm. The ethereal flight of the dove has never again been so vividly mirrored in tones as in the accompaniment to "Die Taubenpost." The rustling of forests and waters fills his works, and with equal mastery, the inner lives of his figures and the realm of spirits turn to sounding motion. Recall the magical effect of the ghostly figure in "Der Doppelgänger," the fearful wails of "Gruppe aus dem Tartarus," the defiance of "Prometheus" against the gods! Consider too the fragrant air in his music for Shakespeare’s serenade, "Hark, hark! the lark at heaven’s gate sings," where the weaving of morning breezes, the chirping of birds, and the blue of the ether meld into a true painting—thus, within a single song, we grasp the singular art of Franz Schubert in its essential worth. The impressions of color and the perspective of sight have pierced the sonic realm of these "sounding primal elements." Every song of Schubert’s is a transmutation of the visual into the acoustic.

And what a psychologist spoke through him! The fevered arc of the boy in "Erlkönig," the rhythmic return of dread in "Die Krähe," the tormenting self-haunting of "Der Doppelgänger," the faint bell in "Die junge Nonne"—all bear a Goethean truth and vividness. How near Schubert stands to history! We feel landscapes resound; castles and cloisters, veiled in legend, rise before us. Nor is it only that he finds ever-new forms for the same natural wonders. How often, how ingeniously, has he set the brook—so akin to the gentle flow of his music—to song! How past and landscape glimmer in the second movement of the great C major Symphony, how a Dionysian sun and joy blaze from the main theme of its finale, a work from Schubert’s final year, uncovered only after his death by Robert Schumann and brought to light by Mendelssohn’s performance at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1839! Austria’s landscape stretches in this mighty symphonic close to the sunlit sky of the world itself. Hans von Bülow wrote after hearing it: "One had dwelt in eternal spaces, in a timeless world."

What flowed from Schubert’s surroundings into his music, lending it an undying enchantment, were two qualities: chaste fervor and a health of feeling. "The Viennese in Schubert is a southern, sensual essence, while sentimentality is a North German affliction," Hans von Bülow aptly remarked, capturing Schubert’s bond with the "milieu" that shaped him. Thus we see a man wholly open, surrendered to the outer world, to whom even the deepest human voices unveil themselves only in sensuous, tangible tones—ever real. None of that boundless exaltation of self above surroundings that marks Richard Wagner, none of the overwrought nervous strain of late Romanticism, nor the hypersensitive, all-consuming "frenzy of Eros." Schubert bears the untroubled Viennese spirit. Unlike Beethoven, Vienna’s great adopted son, Schubert is a native child. Standing today, deeply moved, in the courtyard of the Schubert House on Nußdorfer Straße in Vienna, one must love the plain, untroubled beauty of the Viennese landscape for its own sake, for its folk-song simplicity—so too do Schubert’s character and art present themselves to us. As his life flowed on unassuming, in near-humble modesty, so his art pours forth, from his earliest piano pieces to the grand C major Symphony and the C major String Quartet, Op. 163—discovered only twenty-two years after his death—as an unhindered outpouring of life’s most vital energies. A life lived with and from things themselves—a sensing, a worshiping, wondering, naive, and shattering. Nature dreamed alongside.

While in 1822 the deaf Beethoven, in his Missa Solemnis, wrestled as the loneliest of the lonely, praying and stammering through the tremors of religious awe, standing fearless and defiant before the Highest in the black night of the cosmos, Schubert, in that same Vienna mere streets away, wove the tragic strains of the Unfinished Symphony. In its opening movement, the radiant sunlight of youthful world-joy darkens abruptly, and the chaste zest of early Romanticism falls silent beneath the shadow of fate’s demonic powers. Amid blossoming youth, a foreboding of an early end—the tragedy of a young death.

Nature pours forth countless unremarkable beings, from whose midst a single one, graced with rare gifts, suddenly emerges. Franz Peter Schubert was born on January 31, 1797, in Vienna, at Himmelpfortgrund No. 72 in the Lichtental suburb. He had no fewer than thirteen siblings by the same mother, yet only four besides him survived. His mother, daughter of a Silesian locksmith, was seven years older than his father, whose kin also hailed from Austrian Silesia. The musical gift of Franz Schubert sprang from his father, a schoolmaster in Lichtental. The boy’s extraordinary talents bloomed early. Michael Holzer, his first music teacher, scarcely needed to guide him—everything stirred of its own accord. By eight or ten, he mastered piano and violin; in his eleventh year, on October 1, 1808, he entered the Imperial Choirboys’ Konvikt—not because his father sought to make him a musician, but for the free place it offered, easing the family’s burden of many children.

From early youth, as a chorister and violinist in the Konvikt’s student orchestra, he drank in music as daily bread. This, paired with his rare talent, accounts for his precocious composing. His first spark came from Wenzel Ruziczka, the orchestra’s director, a violist in the imperial court ensemble and Konvikt music master. In 1810, his earliest work took shape: a fantasy for piano four-hands. So fierce grew his musical drive that he neglected his other schoolwork. How little his father cared for a musician’s path is clear from the rift caused by poor grades—Franz was barred from the family home. Only his mother’s death in 1812 brought reconciliation. At last, his father took heed of his vast talent. Anton Salieri, imperial court kapellmeister, then guided the fifteen-year-old’s musical growth. The urge to compose burst free: quartets, piano works, early sacred pieces, songs, and "cantatas" flowed onto the page. Salieri’s ideals halted at Gluck, but Schubert met Cherubini, Mozart’s The Magic Flute, and even Beethoven’s works. Music wholly enthralled him. In 1813, he left the Konvikt. His father, still set against an artist’s life, persuaded him that teaching, though meager, was secure—especially as it spared him the fourteen-year military service then required. This swayed him. Schubert trained as a teacher and in 1814 became his father’s assistant at the Himmelpfortgrund school in Lichtental. Already, a First Symphony in D major had emerged (1813). Lyricism, his truest realm, bore early fruit too. In October 1814, he led his first mass at Lichtental’s church. Therese Grob, his first love—a plain girl marked by smallpox, yet graced with a lovely voice and a warm heart—sang the soprano solos. In Lichtental, Schubert’s name took root. In his lifetime, he scarcely ventured beyond Vienna’s bounds. Too brief was the span granted him.

Schubert had to bow beneath the yoke of his profession, though the task of teaching first-year schoolchildren pressed heavily upon him. Keeping discipline was a trial bitter enough, and he could only enforce it with the rod’s aid. Need forced him to cling to the trade: a yearly wage of 40 gulden—too scant to thrive on, too much to perish. Yet the act of composing filled his soul entirely. Scarcely had he taken up his post when his first masterful song emerged: "Gretchen am Spinnrad" (composed in October 1814). The Second Symphony in B-flat major followed by year’s end, the Third in March 1815. The String Quartet in G minor was flung onto paper in seven days that month. In a mere five, he completed the Mass in G, one of his loveliest youthful works. A second Mass in B-flat major arose, and no fewer than 114 songs poured forth in 1815—a year that not only shaped Germany’s outward fate as a political pivot but also, quietly at first, unseen by his peers, ripened the great song-singer of German art. Schubert gathered his texts with little heed to order. The tempo of his creation, even then, defied explanation and left no room for careful scrutiny. Yet it was no mere chance that the finest poetry stirred his deepest inspiration. At the close of 1815, the 20-year-old set down "Erlkönig" from Goethe’s poem in a fleeting burst. Spaun tells how he found Schubert "all aflame, reading 'Erlkönig' aloud from a book. He paced to and fro with it several times, then abruptly sat, and in the briefest span, the splendid ballad stood on paper. Lacking a piano, we dashed to the Konvikt, where 'Erlkönig' was sung that very evening and met with rapture. Old Ruziczka played it through attentively, part by part, without voice, and was profoundly moved by the work." Thus, the modern art song was born—an unprecedented leap in German music’s history, soaring forth as if on wings, from a moment of blissful, captured inspiration.

Breathlessly, the young genius hurled work upon work. In 1816 came a Mass in C major, the Fourth ("Tragic") Symphony in C minor—a singular piece of that time, unjustly overlooked in Schubert’s full legacy—the Fifth Symphony in B-flat major, and once more a brimming cornucopia of songs, especially to Goethe’s texts ("Der König in Thule," "Mignon," "Gesänge des Harfners"), and those of Mayrhofer, Rochlitz, and "Der Wanderer" (by P. Schmidt), which, beside "Erlkönig," stood as Schubert’s most beloved song in his lifetime.

The weight of his profession grew ever more crushing. The authorities demanded yet another year of training, with no raise in pay. Schubert’s friends crafted the famed dedication of songs on Goethe’s texts to the Weimar privy councillor. Not a single line ever returned from Weimar. The hope that Goethe might accept it, paving the way for a publisher, crumbled—much like talks with Breitkopf and Härtel in Leipzig, who sent "Erlkönig" to Dresden’s royal concertmaster, Franz Schubert, to check if it were one of the era’s frequent plagiarisms. The Dresden Schubert shot back with cynical scorn: he had never composed the cantata "Erlkönig," "but would seek to uncover who sent this same handiwork (!) and unmask the patron who so abuses my name."

They turned to another path to spread Schubert’s name: Michael Vogl, soloist of Vienna’s imperial opera, was won over to his songs after early reluctance. From cold dismissal bloomed the warmest friendship. Schwind sketched Schubert and Vogl making music together; Vogl, and later von Schönstein, became the finest Schubert singers of their day. Yet fate cast a tragic shadow—the singer’s renown eclipsed the composer’s.

Relentlessly, the creative fire drove the young master onward. Piano sonatas took shape (E-flat major, Op. 122, D major, A minor, Op. 164), and in that same year, 1817, "Der Tod und das Mädchen"—a lone bloom of deep melancholy yet timeless glow amid a bouquet. In the summer of 1817 came "Die Forelle," the romantic song’s masterpiece; Schubert had wholly found himself as a composer. Now he must shed the stifling burden of his trade to give himself fully to his true calling.

At last, in autumn 1817, he gained a year’s leave from the school office. The substitute took the salary; the petitioner received unpaid respite. The Sixth Symphony in C major stood finished on paper by early 1818, and on March 1st, Schubert’s first works rang out publicly (two overtures); one song even saw print—what delight for the composer, who could forget he stood jobless, penniless. Just once, he took a post as music tutor to Count Karl Esterhazy’s daughters. Two gulden an hour and a free summer stay at the Zeleß estate in Hungary lured him. Yet the journey there, through summer and autumn 1818, bore scant musical fruit. The teaching life his father sought to thrust him back into was cast off for good. A fresh rift split the family (his father had wed again). Schubert now owned nothing—no home, no piano, no refuge. Spaun and Mayrhofer sheltered him. Therese Grob had wed a master baker.

Unheard-of, the creative storm roared on. From 6 a.m. to 1 p.m., he composed. Afternoons passed with an hour at the coffeehouse, then long walks around Vienna. Evenings brought friends—Schwind, Hüttenbrenner, Bauernfeld, Teltscher—to the inn "Zur ungarischen Krone," where morning’s works were savored at once. So his days held firm until life’s end. Companionship was as vital to him as food and drink. Hüttenbrenner became his keeper of scores. Schubert gave fresh manuscripts away heedlessly, later unsure to whom. A second trip with Vogl to Linz, Steyr, and Kremsmünster sparked anew: the "Trout" Quintet, Op. 114, was penned in November 1819. An operetta, "Die Zwillingsbrüder," graced the Kärntnertortheater, and the next stage work, "Die Zauberharfe," swiftly raised his name. Now the gates of grand patrons swung wide: Sonnleithner brought Schubert to the Fröhlich family. Kathi Fröhlich, Grillparzer’s "eternal bride," championed him. Again, songs flowed freely. Tirelessly, with a bee’s zeal, the genius strewed his gifts, as if sensing how preciously his brief span must be spent.

In 1821, a breach opened between Mayrhofer and Schubert. Schober took in the penniless composer, for Schubert still leaned on others’ kindness. Kupelwieser and Schwind forged warm bonds with him. At last, a publisher emerged—Cappi and Diabelli—yet they shrewdly exploited Schubert’s guileless heart, robbing him of his labor’s due rewards. The Goethe songs appeared and won vast acclaim. A thawing with his father in 1822 finally healed the family strife. Schubert returned to his parents’ home.

A cornerstone of his craft ripened in 1822: the "Unfinished" Symphony in B minor, which, like the great C major Symphony, went unperformed in his lifetime. The Mass in A-flat major bore further fruit that year, cresting a third peak with the "Wanderer" Fantasy. For 20 gulden, Schubert sold its rights to Cappi and Diabelli—a work that, in 40 years, yielded 27,000 gulden! In 1823, illness and solitude struck, yet fame climbed. Singspiels and operettas brought fresh renown. An artful trip with Vogl to Linz shone brilliantly. "Rosamunde," the Piano Sonata in A minor, and the song cycle "Die schöne Müllerin" revealed, amid all distraction, his staggering output in boundless largesse. A second stay in Zeleß bound him wholly; his love for young Countess Caroline Esterhazy seems no mere tale. The masterful A minor Quartet marked a phase of healing and ripe craft. Schubert’s dreaminess and melancholy found their truest voice. Its finale blazes with Hungarian earthly ecstasy. The C major Sonata, Op. 140, hinted at the great C major Symphony of his final year. In 1825, a second journey with Vogl to Upper Austria touched Graz and Wildbad Gastein, but he returned to Vienna with empty pockets. The year 1826 brought the mastery of "Death and the Maiden." Fate, in a soft, mournful tone, drew near the young master; death whispered anew of the hour fixed relentlessly for him. The last Quartet in D minor unfurled all the wealth and vivid freshness of his muse. Unceasing toil, a spare existence, meek pleas for meager publisher fees, endless quests for income, endless disillusion with life itself—we near the peak of this harried life: despite every material blow, the genius’s arc soars gloriously.

Beethoven’s death struck him to the core. Schubert stood among those who bore the body to its grave. He would be next. Dark moods engulfed him; intimations of swift decline lashed his matchless creative force to doubled heights. "Die Winterreise" emerged, the second great song cycle after the Müller songs. In its final part, set down only in autumn, the wrenching weariness of dying’s need and will turned to sound. It is the last faint tread, a death-sad vision of the end—not with late Beethoven’s titanic might, but the mellow autumn of a young life, framed by faded blooms. In the Müller songs, streams and trees sing, joy and Austria’s landscape gleam; in "Die Winterreise," the spark dims to embers. Yet once more, it flared to flame. In 1828 arose the grandest works: the majestic String Quintet in C major, the C major Symphony No. 9, the Mass in E-flat major, song cycles to Rellstab and Heine (including "Der Atlas"), and vast piano pieces. Schubert dwelt with his brother Ferdinand in a new house on Firmiangasse. On October’s last day, 1828, illness took hold. His final aims, for one hailed as master, were touchingly humble: he wished to "learn" strict counterpoint from Simon Sechter, Bruckner’s later guide. The sickness worsened. Strain and erratic living may have sapped his frame. His last tender lines to Schober on November 14, begging for Cooper’s books—author of "The Last of the Mohicans"—paint a helpless "child" tottering feebly from bed to chair. Fever climbed. Bauernfeld later swore typhus had struck. On November 19, 1828, at 3 p.m., Schubert’s eyes closed forever.

Kathi Fröhlich framed his humanity in timeless words:

"All that is noble and grand found a tempestuous echo in his heart. A seeker of beauty, shackled to the woes of a pitiful existence, he had to forge his heaven daily. And he found it in art or beyond his Viennese city’s gates."

Posterity has slowly grasped and shaped his artistic bequest. Schubert’s music is the fairest embodiment of an ideal—rightly seen—of artless art, rooted in nature and the soul’s hidden powers, shunning all that’s forced or strained. He was the "Romantic without fetters," the "musician without doctrine." "The innocence and gentleness of his spirit were beyond words," as a contemporary wrote. He is not merely modern music’s forebear; he stands as the emblem of all German forces flowing as one, embracing all that stirs German hearts—from the South’s sensuous mirth to the North’s deepest musing.

From a youth portrait by Kupelwieser, drawn in Schubert’s 16th year, a precocious, Dionysian lad gazes out, his brilliant eye mirroring all the world’s beauty and joy. When we gauge this fiercely condensed life—its work racing peak to peak, its ceaseless zest—it seems nature, in those scant 31 years, had distilled and laid bare all that thrills our modern nerves and rends our hearts today.