Source Documents: German Scan

Note(s): This article appears in “Der Weg”, a German-language magazine founded in Buenos Aires, Argentina in the years immediately following the destruction of the Third Reich. See the links above for more information on the magazine and its contents.

Title: From the Keep [de: Vom Bergfried aus]

Author(s): Editorial Staff

Subtitle: The Systematic Starvation [de: Die planmäßige Aushungerung]

Author(s): W. Tittmann

Subtitle: Realities About Ruhr Coal [de: Realitäten um Ruhrkohle]

Author(s): Hugo Grüßen

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 2, Issue 2 (February 1948)

Page(s): 127-132

Referenced Documents: None.

From the Keep

The Systematic Starvation

W. Tittmann

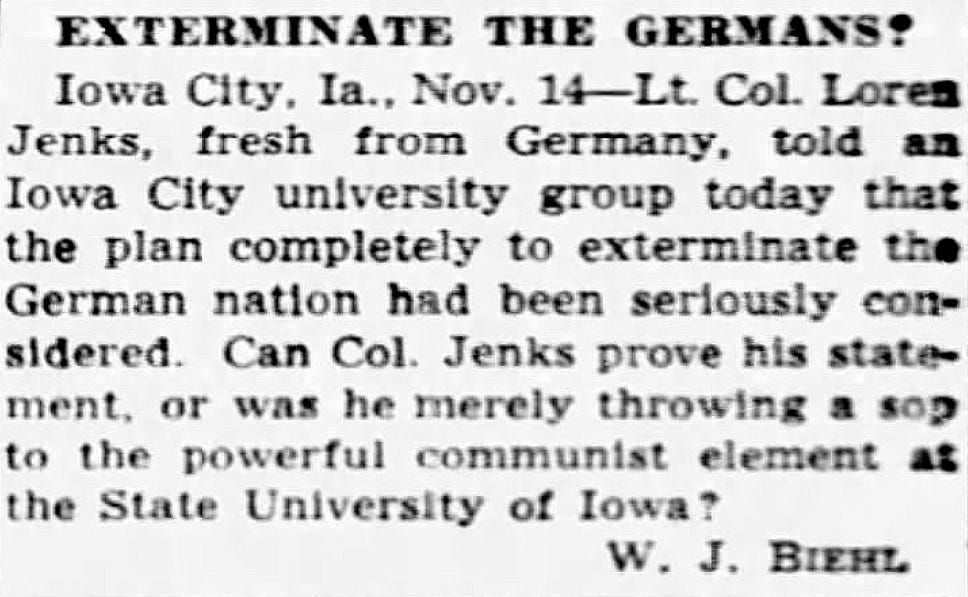

Editor’s Note: In its issue of November 20, 1946, the Chicago Tribune published a letter to the editor so momentous that it truly merited a place on the front page of every newspaper from the West Coast to the East Coast of America.

Under the provocative title "Exterminate the Germans?" the letter declares:

“Iowa City, Iowa, November 14 — Lieutenant Colonel Loren Jenks, fresh from Germany, told an Iowa City university group today that the plan completely to exterminate the German nation had been seriously considered. Can Lieutenant Colonel Jenks prove his statement, or was he merely throwing a sop to the powerful communist element at the State University of Iowa?”

W. J. Biehl

Had anyone, at the war’s dawn, dared to prophesy that a government of the United States would solemnly weigh the total destruction of the German nation as its policy, they would have been carted off to an asylum for observation. Yet this monstrous design indeed held the earnest attention of both Roosevelt and Truman! Of this, there can be no shadow of doubt. Still, as the old adage rings true: No web is woven so fine that it escapes the light of day!

Since Lieutenant Colonel Jenks had only just come back from Germany, this fiendish scheme must have been a whisper coursing through North American military circles, and in a fleeting lapse, Jenks spilled the secret.

It dawned on him that he had dealt a grievous blow to the plan, and when he saw that his careless words had reached millions of Chicago Tribune readers, he sought to mend the breach. On November 24, he had a follow-up letter printed in the paper, asserting that extermination had been one of three options on the table—seriously pondered, yet ultimately cast aside—though he admitted that "for a time, all three plans were being pursued at once."

Rather than softening the crime, Jenks deepens its shadow. Not only does he refrain from denying that an extermination policy was "gravely considered," but he now reveals that, alongside other schemes, this extermination plan "was in the act of being carried out." By this, he confesses that the idea was no mere passing fancy, dismissed as too mad, too devilish, or too barbaric to endure, but that a corps of expert exterminators had lent it their time and meticulous care.

Perhaps the refined circle of the "Saints and Sinners" had Jenks in mind when, at a breakfast gathering on November 29 at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, attended by 1,200 souls including Eisenhower, the latter was depicted on a poster as a "rat hunter"—a portrayal that tickled him immensely, as the New York Times captured him beaming beside his name and lineage.

Lieutenant Colonel Jenks did not say when this satanic extermination plot—known also as the Morgenthau Plan— was supposedly abandoned. Yet its pulsing life is proven not by empty denials but by stark facts and telling silences, all pointing to its ongoing "execution."

The truth of Jenks’s words has since found further echo in Mr. Israel Feinherz, who, with other members of the A.F.O.L., lately journeyed through Germany. In one of his recent dispatches, he writes: "In tackling the challenge of forever quelling German aggression and tyranny, we face two paths: either the complete obliteration of the population or their renewal as a democratic, peace-loving member of the family of nations."

Why he sees only these two roads and overlooks a third—how a conquered land should be treated under the centuries-old tenets of international law—is a riddle only he can unravel. Still, his words lay bare how little the Truman administration, like Roosevelt’s before it, feels tethered to such laws. Here lies fresh proof of the anarchic spirit—or lawlessness—vividly displayed in the Nuremberg Trials.

Even the wariest politicians stumble. Thus, in a speech at the Commodore Hotel, Under Secretary of State Dean C. Acheson paved the way for calculated starvation, proclaiming: "We stand before five years of famine" and "crippling years of fragile peace, years of war and want; these are the trials we face, conditions where the four horsemen of the apocalypse thunder over realms of ruin, threatening all life itself." He neglected to admit, however, that he was among those who loosed these horsemen. With his "five years," he makes plain that this starvation is designed as a slow, corrosive, rotting blight, stretched across the long haul.

Acheson has since risen to First Assistant Secretary of the State Department, stepping into the role of Acting Secretary in Marshall’s absence. His chief claim to this weighty office? That he is the son of an Englishman, fiercely devoted to his motherland and mirroring its sons. Moreover, as The USA News reported on February 7, 1947, he is a protégé of Chief Justice Frankfurter, now his intimate friend, with whom he rides each morning from their Georgetown homes to work.

That same source names him England’s key agent in the Lend-Lease and Bretton Woods talks. He also penned a brochure, shrouded as a top state secret, of which only two copies exist: one locked in the State Department’s vault, the other with the Army Chief of Staff. This document—hidden from America’s "democracy" and even Congress—codifies North American foreign policy.

Thus, North American foreign policy is charted and enforced by a half-foreigner, Mr. Acheson, and a full foreigner, Chief Justice Frankfurter. How strange that a nation of 140 million lacks a single thoroughbred American to guide its fate.

Though some hail us as a "democracy," our government cloaks its policies in secrecy rivaling Stalin’s. They lie veiled behind an iron curtain, withheld from the people and shared only with what Senator Capehart, in a stirring speech, dubbed the "conspiratorial clique."

What the public is permitted to know is painstakingly sifted, polished, and stripped of its true weight, leaving only a grotesque parody of reality. The speeches of these policymakers ring hollow—a truth even the most trusting should now discern. They serve fleeting ends, and once those ends are met, the words linger—mere echoes, never deeds. They are uttered to mislead, to soothe, to dull the people’s wits.

Perhaps not all can be fooled forever, but in our age, with radio, film, "fireside chats," and tools unknown to Lincoln’s time, nearly anything once deemed impossible can now be wrought.

It is a common trick that when a wicked plan is hatched, it comes baited with a lure to divert the eye—like a matador waving a red cape to sway a raging bull in his moment of peril.

Every faint whisper from Germany betrays that the Morgenthau Plan—or extermination scheme—a project so brutally Talmudic it defies a fitting infernal name—is far from being shelved as "unworkable," as those laboring for its success would have Americans believe. No, it surges forward, faithfully followed, and reaps its grim harvest.

The other path Jenks mentioned—supposedly the beacon—of re-educating Germans into "democrats" is but the usual cloak flourished to throw us off the scent. Both policies march in tandem: one for results, the other for deceit. One is true, the other a lie.

The Morgenthau Plan was once thought so lunatic that its execution seemed a fantasy, destined to perish by its own flaws. Yet the outcomes mock that notion. The sadists of Washington, New York, and London, who crave its victory and drive it with united strength, now decry its madness and swear it lies buried in the files. But with the kept press and controlled radio locked in their propaganda pact, all they say demands a wary ear.

The Morgenthau Plan is not the genesis of the German people’s deliberate ruin; it is its continuation. It took root with the "unconditional surrender" demanded by Roosevelt and Churchill. When that call became policy, Germany’s doom was sealed. The noble ruse—that "Nazism," not the German people, was the target—crumbled to dust once its purpose was served. Nazi or not, all Germans are branded as filth to be wiped out.

How far the vaunted "humanity" of the so-called civilized Western powers has fallen is stark in a report painting the British zone as one vast concentration camp, where all Germans are marked as vermin for extermination. Thus, human wraiths drift about, half their weight gone, lost in despair, hopelessness, and lethargy. To their dire woes, they suffer torments beyond all human bounds—many perish from hunger and its diseases, millions hover at starvation’s edge.

Above all, tuberculosis, born of scant food, cuts a fearful swath, threatening to taint the whole German race.

Every peace till now has let a nation breathe, but for Germany and Austria, the victors wage war beyond the ceasefire—not with arms or those "humane" phosphorus bombs, now obsolete, but with starvation’s blade, sharper and cheaper, costing the conqueror less in blood and coin than any other weapon.

Realities of Ruhr Coal

By our correspondent Hugo Grüßen

What stirs in the Ruhr? The red line on the sprawling charts of coal statistics—the ominous 230,000-ton daily production threshold, last notched before the strikes erupted in April ’47—has been crossed once again. On August 15, a new postwar pinnacle was reached with 239,572 tons. Technicians foresee further gains. By material and figures alone, they insist it’s within grasp. Yet predictions are a fickle craft, rarely met with gratitude. Least of all on the trembling, unsteady soil of the Ruhr, cradle to that fiercely coveted black gem, coal. Doubly so when they hinge solely on the promise of bacon and cigarettes.

In every exchange with experts, one contradiction looms large and relentless. “Output could rise effortlessly if only the miner willed it,” some assert. Here stands French Finance Minister Schumann, who penned tales in L’Aube of a miners’ resistance in the Ruhr, aligned with theorists whose rhetoric sharpens to the edge of “sadistic performance decline.” Nor are politicians blameless in forging this view, with their ceaseless claims that only certain political concessions could spur the miner beyond his present toil. It scarcely needs saying that such catchphrases are a gambit, their innocence no shield against peril—a peril whose toll might one day weigh on miners and all Germans alike. Yet it must be stressed: to strip matters of their truth for expediency’s sake is a grave misstep.

Some six months past, when the point system was born, a chorus of old comrades, specialists, and sages rose against it. “We won’t turn into pit shirkers!” an aging hewer bellowed at a district assembly, lending more truth to the matter in one breath than every speaker’s windy orations had mustered. True, the war spared the collieries somewhat. Of 154 shaft complexes, a mere 13 lie idle. A hundred thirty-six deep mines and ten adits hum with labor. Even the lapse in tapping fresh, brimming seams carries no sole burden—it’s a question for tomorrow. Modernized steadily since 1925, the mining machinery—though worn and strained by overuse—still meets every demand. So cutting-edge is it that English miners, recent guests to the Ruhr, marveled on returning home: “West German shafts stand to ours as a Rolls Royce to a rickety cart.” What’s more, recent months proved 50,000 to 80,000 new hands could be trained swiftly. Thus, only a sliver of the gap between prewar yields and today’s—where we muster half that former vigor—rests here.

Only by weighing each man’s output per shift against times of plenty does the shortfall’s root grow plain. In 1936, it towered 43.6% above 1946, and 44.5% over the first half of ’47, despite the point system’s reign. Whispers of sabotage spring from this chasm. True, grave blunders marred the system’s debut. It was cast too wide. What claim have office clerks, say, to special allotments? Worse, its potency was sapped by shaping it into a mere roll-call prize. Yet the heart of the trouble lies deeper still. The question isn’t: Does the miner wish it? It’s: Can he?

“We won’t be pit shirkers!” That anguished cry from the old hewer lays bare the full tragedy. For it’s folly to see the miner alone, the pits apart, and mining as some detached affair that zeal alone might mend. Now they tally for the mate that the point system gulps down 25 million dollars yearly. They chide him that he draws 36 kilograms of cloth annually, while others scrape by with 340 grams—most times glimpsed only on paper. All this holds true—yet it rankles too, not least the miner himself, bound as he is, despite some aid, in our shared ring of want. Of 246,000 homes tied to Ruhr mining, 47.8% bear light scars, 18.3% middling ones, 13.8% grave, and 21% lie in ruin. The oft-touted 4,000 calories feed a family’s bitter hunger. Wives queue for bread too often gone. They trek miles upon miles for potatoes, bartering what their men wrest from grueling shifts. For some, the trek to the pit eats half a workday, with transit still frail. Work garb frays to threads, replacements rare. Factor in that miners’ average age runs 10 to 12 years too high, and new hands arrive unseasoned, and the myriad curbs on higher yields stand clear.

A curious thread goes too little noted. Scores of youths fled the Ruhr to toil in mines across Europe. Why so? The labor there is no less harsh, the social lot sometimes meaner. Because, for all his extra rations, the Ruhr mate dwells leagues from the modest ease his foreign peers know. More than the common worker he may claim, yet far too little still. Here the mind’s tide turns. Can uncommon effort be asked of him when he senses the coal he hews—coal that might yield bread for his famished young via fertilizers, or homes via brickyards—rolls off in hundreds, thousands of wagons? Isn’t goodwill the bedrock of any outsized push? Man, even one as broken as Germany’s now, craves a loftier aim to summon all his might. His task must whisper deeper purpose. And faced with the daily drift he witnesses—partakes in—amid a despair that finds no flicker of reprieve, it’s little wonder no new spark ignites. The gnawing sense of being wielded, even bled, for alien ends lingers unshaken in him. To counter this with bacon, with cigarettes, is a lost cause. A few thousand might stoke the fires briefly, but the surge soon fades. Lasting motion demands more.

Fresh currents loom near. A restless hum grips the coal towns, unseen for ages. Seers reckon the weeks ahead will fuel Ruhr talk for years. Three hundred million dollars shimmer like a desert vision above the rubble—food, roofs, clothes, wheels, tools, machines—all that sum could weave. More coal, too, if it births no new “bacon scheme.” The Ruhr could wield it well. It might spark the dawn we’ve chased in vain, a fanfare for a “Peace Ruhr,” should we heed the knot binding man and coal, Ruhr and Germany, Germany and Europe as one.