Title: Life in Expectation [de: „LEBEN IN ERWARTUN“]

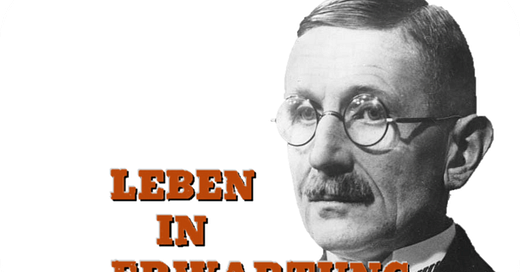

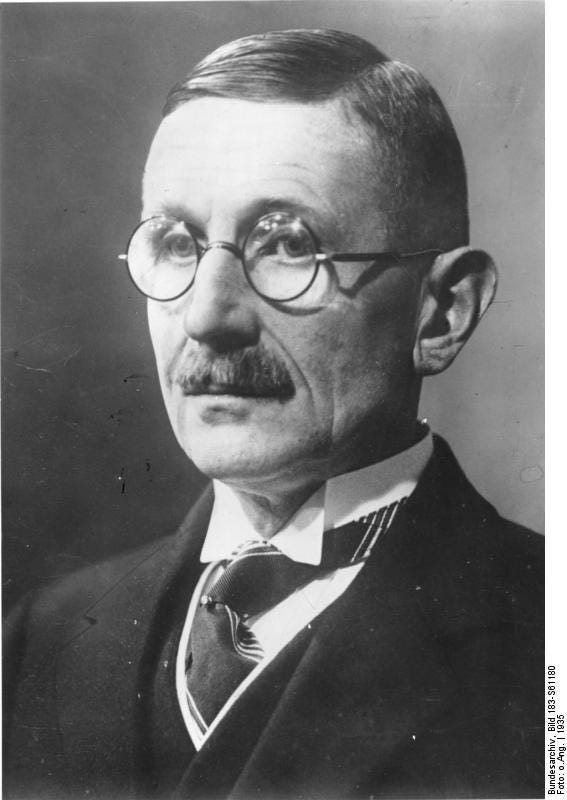

Author: Hans Grimm [LINK]

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 02, Issue 11 (November 1948)

Page(s): 772-775

Dan Rouse’s Note(s):

Der Weg - El Sendero is a German and Spanish language magazine published by Dürer-Verlag in Buenos-Aires, Argentina by Germans with connections to the defeated Third Reich.

Der Weg ran monthly issues from 1947 to 1957, with official sanction from Juan Perón’s Government until his overthrow in September 1955.

Source Document(s):

[LINK] Scans of 1948 Der Weg Issues (archive.org)

Life in Expectation

by Hans Grimm

Through the Academic Exchange Service, during a stay in London in 1934, I was invited to Brighton for a meeting of friends of the League of Nations—the exact name of the society escapes me now. The London director of the Exchange Service, who was not a member of the NSDAP, and a clever young man employed by the Exchange Service, who had belonged to the early SS, were to speak there about National Socialism in Germany and answer questions, which they undertook in an honest manner.

After the meeting, there was tea, and before departure, we German guests were hosted by a retired English general. Once the speeches and general discussion were over, and the tea was served, informal groups gathered. Three or four older priests of the High Church approached me; they claimed to have connections with archbishops—one, if I remember correctly, with the Archbishop of Canterbury, the others with the Archbishop of York. They explained that they had come to inform themselves and had perhaps arrived a bit late.

They asked if I was Dr. H. G., the German writer. They had been told that I, for my part, did not belong to the National Socialist Party. Might they inquire whether that was accurate? And if so, was I willing and did I consider myself authorized to answer a few questions personally, not for publication?

I naturally declared myself willing. For even if we sensitive souls had already been stirred and perhaps made uneasy by some aspects of the ruling National Socialism, in May 1934, hope still persisted—as did the burning will to hope—in all of us who felt our Germanness as our destiny. And to be frank, the thought of possible personal danger from speaking openly, should my words be spread further, certainly occurred to very few at the time, and not at all to me.

The questions put to me calmly and eagerly contained no barbs or traps. Unfortunately, I did not write them down the next day. I must reproduce the questions and answers as they resurface in my memory whenever I see the three or four churchmen with their clever and inquiring faces before me.

“Doctor, are you then an opponent of the Party?”

“Why do you think that, because I do not belong to it? I do not belong to it because, in my conviction, a writer—we Germans would probably say a poet in this case—as little as priests and judges, should pledge themselves to a party.”

“Doctor, do you make a distinction between National Socialism and the Party that strives to realize it?”

“I believe I do make a distinction.”

“And does National Socialism, as you conceive it, attract you more than the Party?”

“That may be said.”

“Do you know the goals of National Socialism, and are you familiar with the Party’s program?”

“I have read the program; much of it does not matter to me at all. However, neither the Party nor, even less, National Socialism came into being through the program, nor did they attain such rapid power through it.”

“Doctor, in your opinion, how did it all begin?”

“Gentlemen, I believe you are now asking the most important question. Please do not take offense at my attempt to answer as briefly and soberly as possible, neither as Englishmen nor as churchmen.”

“Gentlemen, in England, over the last thirty years, the German youth movement has often been discussed. You will admit that in this youth movement there was a passionate will for a second Reformation. The boys and girls demanded that being replace pretense, that man no longer attribute to God what he could achieve himself with proper effort; they wanted deeds instead of fine words; they insisted that carefully considered care for spiritual and physical health and recovery become the first duty of the state and the individual. Every convenient half-truth should cease to hold where, with effort, a whole, even if initially harsh, truth could be attained. Part of these demands was a new social attitude, under which there should be no more political class struggle, and every good gift in every compatriot should be allowed to develop fully and unimpeded, and every achievement should receive its full reward.”

“Gentlemen, these are the goals of the faith, hope, and will with which the thinking German youth of 1914 marched singing into the war. The youth had almost nothing to do with what was attributed to them by any political state propaganda or alleged by political party propaganda.”

“Gentlemen, the thinking youth who survived the war reaped Versailles. A reformation of human nature did not take place in any way. A victory was thoughtlessly exploited against them, and nothing else. Germany was dismembered. In the severed territories, the severed Germans had to perform military service for the new masters in the future; others were expelled. The European eastern wall, held by Prussia-Germany and Austria-Germany, was undermined. To all the unfortunate things that happened, economic restriction was added.”

“Gentlemen, at that time—still before Versailles—when the English Member of Parliament E. D. Morel appeared in Berlin in great concern about impending disaster to establish Germany’s last immutable condition for life, I had the phrase I found as an answer, ‘Volk ohne Raum’ (People without Space), conveyed to him.”

I pointed out that we, a diligent and gifted people with the most Nobel laureates, were situated in a land that was not rich in itself and had the most limited opportunities. If one were to take even more opportunities and rights from this materially poorly endowed people, it would necessarily be driven en masse towards upheaval and Eastern Bolshevism. I have since learned that Morel shared this view from the outset with others. However, he did not prevail.

When I paused for a moment to collect my thoughts in English, one listener said,

“Doctor, this all is very interesting, I am sure; but what are your young men up to now?”

I replied,

“Gentlemen, you must not take offense at my preamble; I know that in England, in a political dialogue, the causes are not gladly heard. However, you wanted to know from me how it all—National Socialism, the Hitler Party, and their seizure of power in Germany—came about.”

“Gentlemen, to the by no means extinguished, but more than ever burning will among our thinking youth for an honest clarification of all the long-gambled human relationships, the monstrous economic distress made itself felt as a consequence of Versailles for the entire people, and most of all for the youth. All paths of inclination and hope seemed and were blocked for the youth. And then, the unnecessary humiliations inflicted on the defeated ate away at certainly not the worst in the people.”

“Gentlemen, in 1933, before the seizure of power, there were 6.5 million unemployed in the mutilated German Reich, and between 1919 and 1933, around 250,000 people in the mutilated German Reich took their own lives out of despair.”

“Gentlemen, this is how it all began, and from these conditions, everything followed. Gentlemen, perhaps it benefited Hitler that he was an Austrian German. Among the other German tribes, there was an old friendly inclination towards the Austrian Germans. Perhaps it also benefited Hitler that he came from the common people and that the fermenting masses felt him as one of their own, and that precisely his humble origin was credited to him by the dreaming, hoping youth.”

At the end of the conversation, I said that I would now try to explain what the “marching young people” in our country were aiming for, specifically in terms of foreign policy and Europe, as that was probably what most interested the questioning gentlemen and myself.

“Gentlemen, it will sound strange to you when I assert that our fate and the development of National Socialism in terms of foreign policy and Europe will depend on England’s stance towards Germany.”

“Gentlemen, except during the years of the Boer War and the kind of propaganda with which the Boer War was justified in the British public, there has never been for any other nation among us so much readiness and never such genuine kinship feeling as for England. But at no time were the people and leadership among us so united and so outspokenly convinced that a better future for Europe and Germany alike could only be brought about in agreement with this England and with the preservation of all the good forces of the British Empire as now. The immediate cause of such conviction among us lies in the horror of the massification and communism of the East, which are still almost foreign to you, but which we not only notice maliciously at our unprotected eastern border but partly already have in the country, indeed, in essence and kind, begin to have in our blood.”

I added,

“Gentlemen, so far, nothing decisive has happened in terms of Europe and foreign policy. Clumsiness and exaggerations may have occurred on our part. The figure of Hitler may displease you, but if official England understands Germany anew, and indeed from the English lordly essence rather than from the resentful competition, then you, and probably only you, can make the German Reich the strongest and most reliable friend and the surest preserver of Europe. All that will lie much more with you than with us under our necessarily unstable conditions…”

In the course of these notes, I have repeatedly had to confess that, due to my Low Saxon heaviness, I have never been dialectically skillful. To my deep regret, I have also never succeeded in convincingly addressing an English listener on the European matters that have always seemed to me to signify a German-English commonality and that have become increasingly tangible. When my heart is heavy with expectation and fate, and my voice tries anew to establish the explanation, the polite response “very interesting, very interesting” is unspeakably discouraging.