Title: Voices of Germany [de: Deutschland-Stimmen]

Author: Der Weg Editorial Staff, Anonymous Letters

Issue: Year 01, Issue 04 (September 1947)

Page: 244-248

Dan Rouse’s Note(s):

Der Weg - El Sendero is a German and Spanish language magazine published by Dürer-Verlag in Buenos-Aires, Argentina by Germans with connections to the defeated Third Reich.

Der Weg ran monthly issues from 1947 to 1957, with official sanction from Juan Perón’s Government until his overthrow in September 1955.

Source Document(s):

[LINK] Scans of 1947 Der Weg Issues (archive.org)

Voices of Germany

We are ever thankful for submissions of European letters, personal accounts, newspaper clippings, poems, and photographs. All contributions are handled with the utmost confidentiality. Yet, we bear no responsibility for the accuracy of their contents or the opinions they express.

We present here a revealing letter, one that paints a factual and detailed portrait of Germany’s present state:

J. Sch. to W. A., Bremen, February 1947

As I noted at the outset, the coal situation has steadily worsened into a catastrophe since the first cold wave struck on December 12, 1946. People speak widely of a “coal crisis,” its effects so devastating to economic life that any attempt to describe it falls pale beside the stark reality. I cannot, of course, judge whether the causes stem solely from meager production or if other factors hold sway. But it’s not just a coal crisis we face—there’s a shortage of spare parts, a breakdown in repairs, a faltering power supply: in short, a cascade of crises sparked by deficits in raw materials, tires, packaging, transport capacity, fuel, and even light bulbs. Indeed, one might now speak of an “eyeglasses crisis.”

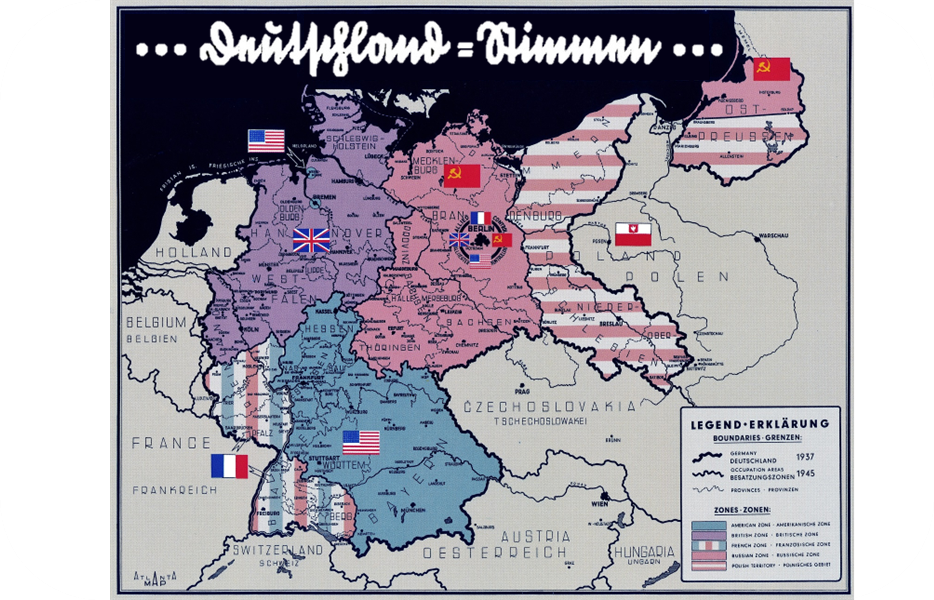

Where do the roots of these crises lie? First and foremost, in the zonal boundaries. Shipping goods from the British Zone to the Soviet-occupied territory feels like a trade deal between nations with no diplomatic ties—countries that, despite their mutual reliance on each other’s goods, must barter through third parties in a tangle of cumbersome compensation and clearing processes. German industry, once a finely tuned machine drawing supplies from across the nation based on cost and capability, now finds its lifeline severed; the flow of parts and raw materials, even in the smallest amounts, is choked off—spare parts being the prime example. You’ll recall that 95% of the ball-bearing industry sits in Schweinfurt; if a bearing fails today in a southern Black Forest factory and none lies in stock, solutions come at a steep price.

The second critical blow fueling this dire state is the dismantling campaign. Permission to restart a factory whose supplier has been stripped bare is little more than a mirage. The dismantlings, sadly, lack any organic plan—new lists of targeted plants emerge sporadically, sowing paralysis across operations. A sword of Damocles dangles over countless firms, and we can only hope the looming peace talks will draw a line under this ordeal. It’s almost unthinkable that, from a Germany reduced to rubble, functioning factories are still being pried loose to bolster production in nations—some quite wealthy—abroad. Just days ago, I read that the first reparation shipments, laden with tools and machine tools, reached Australia.

Then there’s the notorious labor shortage, another thread in this tapestry of woe. Five million prisoners of war remain trapped in former enemy lands. Releases from Soviet captivity, for instance, are scant—only the sick and unfit for work are sent back. From Britain, 15,000 men return monthly (some 400,000 linger there still), while France digs in its heels against freeing 600,000 Germans, even coaxing volunteers through advertisements to stay and offset their population gap. What anguish hides within this plight! Children pine for fathers, wives for husbands, parents for sons. The thought that all these captives might return soon is unimaginable, though the Hague Convention grants even defeated powers the right to reclaim their imprisoned men once hostilities cease. How powerless we’ve become—this, perhaps, proves it best.

The food crisis I flagged in my last letter has only deepened since. Despite every promise, the standard of nutrition keeps sinking; a single example says more than a flood of words: At the start of the new ration period (four weeks), adult fat allotments rose from 200 to 250 grams. The newspapers trumpeted this “progress,” while announcing children’s rations would be fixed at 350 grams—down from their prior 450. A family of three children once received 2x200 + 3x450 = 1,750 grams; now, it’s 2x250 + 3x350 = 1,550 grams over four weeks. No further comment needed.

We all know Germany cannot grow enough food to sustain itself. Yet we also know intensive fertilization could boost yields. That’s impossible now: ammonium sulfate production is tightly capped, nitrogen output is bound by strict quotas, and potash—either under-mined or over-exported—slips beyond reach. Our natural fertilizer factories—cattle herds and pigs—are slaughtered en masse, deemed an inefficient detour for plant nutrients by the Allied occupation powers.

Moreover, only robust exports can secure vital food from abroad. But how can we export when our industry withers more each day? Workshops stand idle without coal. Trams halt in the dark, lacking bulbs. People cannot work—there’s no food, and even eyeglasses elude them.

That last point may sound absurd, but it’s a bitter truth. The near-total dismantling of Germany’s optical industry has birthed a shortage with grim ripples, its full toll yet to unfold.

As I wrote before, steel production is severely curtailed. I can offer figures now: the Allied Control Council Law sets Germany’s target at 5.8 million tons. In 1946, we managed just 1.8 million. This paltry yield mirrors our crisis—bombed-out plants, often roofless, with shoddy machines and scant coal allotments, yield no real output.

Another curb on production, it seems, is the recent decree banning corporate mergers in Germany. German firms are barred from joining foreign cartels, and even foreign investors are locked out of our industries and businesses. I can’t predict the fallout, but one thing is clear: German groups can’t amass capital under this crushing tax burden—rebuilding a robust industry likely hinges on foreign funds. There’s a sliver of protection for Germany in this, admittedly; a currency imbalance could see our firms snapped up cheap. Whether these measures misjudge Europe’s modest scale against America’s sprawling economy, I cannot say. The existing weave of foreign capital here—think General Motors at Opel, Ford in Cologne, Shell at Rhenania-Ossag, Maizena, Brown-Boveri, American stakes in AEG, Belgian interests in our steel—must somehow factor in. German interests abroad? They vanish silently into other nations’ economies.

Shall I touch on reparations? As I understand it, payments from our remaining factories are slated for 18 countries. Territorial claims arise from the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Soviet Union—early on, even Austria eyed German land. Luxembourg’s stance escapes me, but only Switzerland and Denmark, to my knowledge, have abstained from such claims. I can’t detail each nation’s demands; you’ll likely see them in your papers soon enough.

Tied to this are the war damage tallies: Poland lists 11.5 billion dollars, Yugoslavia 9.5 billion, Austria 7 billion.

And Germany? Internal debt is pegged at 800 billion Reichsmarks. Compare that to our national wealth—roughly 250 billion Reichsmarks. In our best year, national income hit 80 billion; now, I’d guess it’s a third of that.

An article, The Direst of Distresses, sheds light on the German Reich’s utter collapse. I can’t recount it all, but consider this: expulsions from Poland unfolded in 10-to-20-degree frost, with bare freight cars—no heat—rolling into Germany, and people permitted only the barest scraps of belongings. That speaks volumes. If memory serves, 1.5 million Germans were expelled from Polish-held lands; from Czechoslovakia, perhaps 2 million. These poorest souls huddle in barrack camps, uniquely vulnerable, as German agencies can no longer aid them—mostly women, children, and elderly men. This age skew cripples our economy—I’ll return to that.

From The Direst of Distresses, a few trifles: no shoelaces or decent twine exist—only those wrestling a brittle, ten-times-knotted lace can grasp what that means.

No writing paper, no bandages, no matches, no medicines, no bulbs; we lack combs, thread, darning wool, pins, needles, shoe polish, toothpaste. Hygienic goods are gone. Pots, cups, scrubbers, buckets? Unattainable. In short, everything’s missing. These are just the small things, mind you—clothing’s been absent for years. You know the food and heating struggles already.

The health toll is horrific. December brought 5,000 new tuberculosis cases in the British Zone. Once vanquished here, this scourge now rages as a national plague amid our plight. Hunger edema is commonplace. Typhus and dysentery flare sporadically. Venereal diseases surge anew. Bremen’s counseling center logged 829 cases in 1944, 1,528 in 1945, and 3,012 in 1946.

The October 29 census revealed demographic shifts. Within shrunken borders, we’re about 66 million. Add those from eastern territories and 5 million prisoners, and we’ll near 72–74 million. War losses—6 to 8 million—have aged us terribly. With 2.7 million war-disabled here, 5 million able-bodied men captive, and male expellees often detained, our labor shortage persists despite the numbers. Statisticians warn: at this birth rate, only 43 million will remain by 2000.

On domestic politics, note the push for socialization, land reform, and school rebuilding. For your interest, a word on schools: debates rage over community versus confessional models. The staunchly church-tied CDU seeks confessional schools—or at least secular ones with heavy religious sway—claiming parental rights trump state law. Parents’ natural right to raise their children, they say, is the school’s moral compass; flouting this is undemocratic, a step toward tyranny. The SPD counters: education must shed its class bias, open to all children alike. Religion should be optional. Re-educating the nation democratically starts with the young—outranking parental claims.

A telling domestic sign: a state treaty between Bavaria and Greater Hesse ensures mutual Abitur recognition, sparing Greater Hessian students disadvantage at Munich’s university. Yes, a treaty was needed.

As I wrote before, Germany’s teacher shortage bites—denazification clips universities hardest. Papers say regular classes are sometimes impossible. Coal scarcity ensures no proper schooling anywhere—at 15 degrees Celsius outdoors, unheated rooms won’t do.

From a Letter from Lusatia

B..., October 2, 1946

Fate has battered us these past 1.5 years, leaving me still struggling to voice our tragedy. Miraculously, Lusatia’s eastern fringe escaped combat. Bautzen bore brutal street fighting; Zittau took bomb damage on the war’s last day. The early occupation days terrified our women. Late May saw Soviet troops yield to Polish ones, who acted decently at first. We surrendered bicycles, motorcycles, and radios, but life seemed to normalize—until June 22, 1945 (mark the date: the anniversary of the Russia campaign’s start), when a thunderbolt struck. At dawn, whip-wielding hands drove us from our homes in half an hour to an hour. First, we could take only what we could carry; later, a small cart was allowed. I’ll spare you the scenes—imagine what fits on a handcart. Stunned, we forgot essentials. Valuables—good shoes, linen, clothes, bedding—stashed against looters, stayed hidden under Polish eyes. Half-numb, with meager possessions, we left that morning, quietly hoping the Poles just wanted a thorough plunder and we’d soon return. Today, we know that hope was false.

Herded onto a sports field, we stood hours before this “train of misery” (in its old sense: in eli lendi—to another's land) lurched toward Zittau. A fierce storm drenched us en route; we reached Zittau soaked by 9 p.m.

There, mocking “solidarity” posters greeted us: “Expellees and refugees, press on to Mecklenburg and Pomerania—space abounds there; Saxony’s too full for shelter!” What a warm welcome from our district! We refused that path—East Prussian and Pomeranian masses had already swamped Mecklenburg’s “ideal” space for months. Saxony just wanted us gone. So began the “new masters’” care. I broke from the train in Zittau with others, heading for Schlegel-Burkersdorf, but Polish riders soon whipped us back. In town, we slipped away, crashing with friends that night. Next day, the misery train was shunted from Zittau—like outcast Romani of old—marched toward Mecklenburg with grand promises. Yet, in nearby Gobau, naive settlers were halted and, days later, bounced back to Zittau by Soviet authorities. We moved on the second day to …, finding refuge with ….

Can you, so far off, fathom the grief that’s crushed our land and people? Thinking the war’s end marked our suffering’s peak, we were sorely wrong.

We former Party members get “special” treatment. By November 1945’s end, even the mildest Party teacher—like all public servants—was sacked. In Saxony, that hit nearly every educator. Untrained, jobless street recruits replaced us before the youth—some lay teachers provably lack basic math or spelling! Picture that chaos. The dismissed—our nation’s intellect—scrape by as laborers (63 pfennigs an hour), odd-jobbers, and such. We’re criminals now. I toiled dismantling for the Soviets last spring; since June 1946, I’ve “graciously” loaded coal (87 pfennigs hourly) for the “reconstruction.” Ex-Party folk like me hang loose here. The job’s lone perk? Beyond wages, we can claim a coal ration—80 quintals of briquettes yearly. Amid next winter’s coal drought, that’s gold! We’ve three cares now: health, food, heat. Lose those, and death’s our only release. In our zone, all values are upended—what’s left for us? That’s the bleak sketch of our present and shadowed future.

M. E. to R. P., Münster, May 1947

One truth stands firm: despite Europe’s ghastly woes, we’ve plenty to laugh at from where we sit. I say we’ve no cause to droop our ears—sharpen them instead. Pity you can’t, from afar, survey Europe’s scene—the grand chessboard of an era’s turn. Even you’d find comfort in history’s wry jests surfacing now, easing this grim wait. Europe’s whirl tests our bearings, but a keen mind sheds the sense we’ve been orphaned, left “fatherless and motherless.” Never forget this war’s purpose—we were raised to question, not to hate other peoples. It was a clash of worldviews, its front not dividing nations but slicing through them all. Ponder that, and you’ll trace the truth. One thing mustn’t cloud your view: blind faith in Germany or some lofty justice.

Meanwhile, we amuse ourselves with daily politics—like April 20’s state election. Münster boasted—get this—53% voter turnout (eligible voters, mind), counting spoiled ballots venting righteous fury and excluding millions of captive German men. Barely a third spoke, split among five parties brawling absurdly in the “campaign.” That’s a “freed” folk! We manage with the occupiers—boy, they’ve much to learn! When Britain’s Foreign Secretary lately confessed, “It’s shameful a victor woos the vanquished for ideology’s sake,” who’d argue?