Source Documents: German Scan

Note(s): None

Title: Women’s Work [de: Frauenwerk]

Author(s): The Editor, Charlotte Thomae, R. M. Rilke, Hausjürgen Weidlich

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 1, Issue 5 (October 1947)

Page(s): 393-196

Referenced Documents:

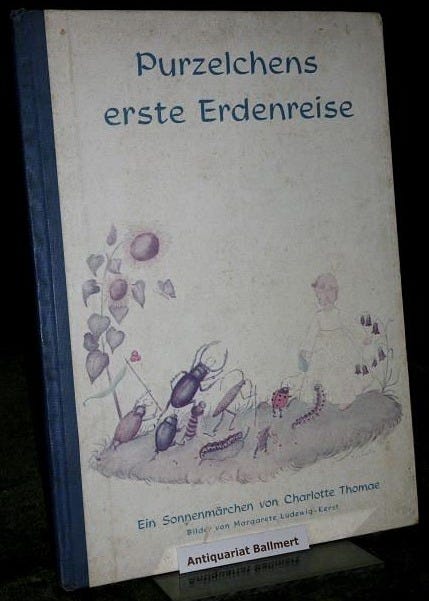

Purzelchens erste ErdenreiseZwerg Nase

Die Reise nach Mexico

Blinki, das neugierige Sternenbübchen

Rainer Maria Rilke to his wife, Clara Westhoff, on November 12, 1901

Letters of Rainer Maria Rilke, 1892-1910, translated into English by Jane Bannard Greene and M. D. Herter Norton.

The Editor: The renowned Austrian writer Charlotte Thomae, now residing in Buenos Aires, where her latest work, Purzelchen’s First Journey to Earth, is being published by Dürer-Haus, shares here how the sunshine of a radiant soul found form in fairy tale books amid the shadows of the post-war years. Indeed, it is a small story, yet one rich with truth.

How I Came to Write Fairy Tale Books

It all began in school. It was a deeply romantic place, nestled within the enchanting Benrath Castle near Düsseldorf. Gazing out the classroom window, one’s eyes would settle on a lake, its surface cradling a tiny island where willows and birches swayed gently. Beyond the castle stretched a vast forest park, reaching down to the Rhine’s banks, its quiet avenues and dreamy ponds adorned with floating water lilies. I cherished this school dearly, and above all, the path I took each morning through a chestnut-lined avenue in that woodland. How lovely it was in spring, with birdsong filling the early air, the tender greening and blossoming all around; in summer, a flood of sunlight filtered softly through the canopy of broad treetops; in autumn, delicate mists hovering over vibrant hues; and in winter, the freshly fallen snow lying pristine and untouched in the forest park. Yes, I adored that path—it was the very thing that stirred my first childish lyrical poems.

Yet the essay topics assigned in German class, so stark and sober, I stripped of their dryness, weaving them with figures from my imagination until they blossomed into true fairy tales. Later, I shared some of these tales in youth magazines. My German teacher, who had a marvelous gift for bringing German literature alive to us children, took great pride in my essays, reading them aloud to the class and declaring with certainty that I would one day write fairy tale books. I rejected that notion with vigor, for my sights were already set on following Schiller’s path, crafting revolutionary dramas.

For days, I wandered about with a brooding expression, until at last I began to “compose” a grand, bloodthirsty drama: Love and Revenge of a Bayadere. To recount its full tale would take too long—suffice it to say the four acts spanned no more than two pages each, and by the close of the fourth, the stage lay strewn with corpses. It was a shattering work, indeed, and one with consequences: it earned me a poor mark in mathematics (for I had chosen that hour to weave my verses), a slap from my father as a result, and—most remarkably—the acquaintance of a great woman, Luise Dumont, the General Director of the Düsseldorf Theater.

Once I had finished Love and Revenge of a Bayadere, I sent the manuscript straight to the Düsseldorf Theater, awaiting with bated breath the invitation to my drama’s premiere. But, unbelievably, eight days passed with no word, prompting me to march grimly to the telephone and ring the general directorate. The call bore fruit: Luise Dumont summoned me to meet her. I had no choice but to confess the drama to my parents, who received it with good humor, and so, armed with a bouquet of flowers, I made my way to the theater. Luise Dumont, by then an elderly lady with white hair and dark, sparkling, wise eyes, must have been quite taken aback to find a little girl with pigtails standing before her. Yet I was utterly captivated by this witty, commanding woman, by the Düsseldorf Theater, and by the prospect of studying under her after school. I even forgot my Bayadere’s thwarted stage debut, setting to work diligently on Dwarf Nose, a fairy tale play she tasked me with adapting.

When I parted from my school and my German teacher, she wished me much luck on my journey, though with a touch of sadness she remarked that the theater’s atmosphere would soon make me forget the fairy tale world. For a long time, she was right. In the years that followed, spent at the Düsseldorf Theater, the Mannheim National Theater, and the Munich Kammerspiele, I immersed myself solely in the stage—dramaturgy, directing, and radio—penning only the occasional poem or sketch, but no more fairy tales. Even later, as fate carried me crisscross through foreign lands, fairy tales did not cross my mind. Instead, I wrote my first novel, The Journey to Mexico, published in 1943 by Berlin’s Zeitgeschichte-Verlag, followed soon after by a second novel, set to appear shortly from a Vienna publisher.

Then came the heavy Christmas of 1944, a time of war’s weight. I had no gift for my two children. Recalling how well I once spun fairy tales, I resolved to place a Christmas tale beneath their tree. While they frolicked in the Tyrolean snow outside, I sat at the typewriter, bringing to life Blinki, the Curious Little Star Boy. It was ready just in time for the Christmas table, delighting my children immensely. In 1946, a Vienna publisher released it as a book, and having once more taken up the fairy tale quill, I wrote a second tale for the same house. Now, living in Buenos Aires, I’ve crafted a third for Dürer-Verlag. May the sunlit story of Purzelchen’s First Journey to Earth bring joy to the children of the German colony here, and how it would warm my heart if one such little soul wrote to me, sharing their thoughts on Purzelchen, the sun child, Mr. Pointy Nose the hedgehog, Miss Gray Hair the mouse, and Mr. Melodious the frog. Even now, as in my school days, I may roam with a somber look and myriad plans—not for a bloodthirsty drama, but for episodes from life’s own theater—yet ever and again, I’ll return to the fairy tale realm, conjuring it anew for our little ones.

Dear Helmuth, do you know what struck me the most? I noticed again that many people use things for silly reasons, like tickling themselves with peacock feathers. They don’t take the time to look closely and appreciate the real beauty in these objects. Because of this:

Most people miss how wonderful the world truly is. They overlook the splendor in small things—like a flower, a stone, tree bark, or a birch leaf. Adults often get caught up in their busy lives. They focus on jobs, worries, and minor problems, slowly losing sight of the beauty around them. But children, when they’re curious and kind, see these treasures right away and love them with all their hearts. Wouldn’t it be amazing if everyone could stay like that? If people kept their simple, heartfelt wonder and never stopped finding joy in little things—like a birch leaf, a peacock feather, or a crow’s wing—just as much as in big things like mountains or palaces. Small things matter as much as large ones. The world is full of a great, timeless beauty that touches everything, big and small alike.

R. M. Rilke

The Bouquet

By Hausjürgen Weidlich

It was morning, ten minutes shy of eleven. Herr Fiebelkorn was due at the municipal office by the hour. The building stood right beside the theater, so he paused before the theater’s display cases—he had five minutes to spare, and actors always intrigued him, actresses most of all.

Suddenly, he froze: a photograph caught his eye, a name beneath it. He read it again—no mistake. It was her: Lisbeth Schlichter.

His face flushed red, his heart thumped loudly. In an instant, he was once more the boy who’d tried to bring flowers to the “Naive” in his hometown. Twenty-five years had slipped by since then; for at least twenty, he’d heard nothing of her. The last whisper was that she’d been engaged far off, in a larger city, as a “Sentimental”—and now, here she was again, looking, remarkably, just as she had.

Herr Fiebelkorn nearly missed his appointment, so shaken was he by this encounter with her image and name. It had been a grand love, after all: a boy’s first devotion to an actress.

Alas, the meeting meant he’d be tied up with business friends that evening. Go to the theater with them? No! If he were to see Lisbeth Schlichter again, it must be alone.

He paused at that thought. What an idea. And without hesitation, he acted: he wrote her a letter.

It was more the outpouring of a lovestruck lad than the words of a grown man, a letter she read that very evening in her dressing room:

“I recall your roles in Peterchen’s Journey to the Moon, as Wilhelm Tell, as Franziska—I even remember the dress you wore in that part. Back then, I loved you. Yes. Loved, as only a third-year schoolboy can.

You lived on Ferdinand Street—I can still picture the house exactly—the stairs creaked as I climbed toward your apartment, clutching my bouquet. I truly climbed—I, the little schoolboy, up to the heights where you, the great actress, had lifted my love.

My heart pounded so fiercely that I knew, if I stood before you, not a word of my fine speech would escape me. Still, I pressed on. Then I heard a corridor door open above, your voice—and in that moment, I turned on my heel, raced down the stairs, bolted out the front door, around the corner. From there, I watched you. A second visit? I hadn’t the courage.

This morning, seeing your picture, reading your name, my heart raced once more.

And yet: today, I’d like to bring you that bouquet, and I wouldn’t turn back—if I may come. May I?”

The actress hadn’t known such joy in ages as this letter brought her. With it, the days of her beginnings sprang to life again: she saw herself as Franziska, recalled that dress—the first with a deep neckline. Oh, how glorious that time of firsts had been! Everything new, everything unfolding for the first time.

At dawn the next day, she rang Herr Fiebelkorn. He answered with a manly tone, only for his voice to soften at once into a shy schoolboy’s. How awfully kind of her to call so soon! Had his letter been too bold, perhaps?

“No!” she cried, slipping back into the carefree Naive of old. “It’s just as it is—wonderful! Exactly right. I can see you climbing those stairs, turning tail, dashing out the door, peeking around the corner after me… oh, how this letter delights me!”

How awfully kind of her, he said. “Do you remember? ‘Oh, father, look at the hat there on the pole… ha, ha, ha!’”

Did he remember? Oh, yes! He’d seen Wilhelm Tell twice, after all. And Minna von Barnhelm thrice—because of that dress.

“And when shall we meet, truly? Are you free this morning? Right now, even? Or shall we lunch together?”

He couldn’t very well bring the bouquet then—he’d feel shy before others.

“But the bouquet was in your letter already! No, leave it be! Just tell me: what do you look like now, so I’ll know you?”

No need to worry—he’d recognize her at once, he assured her.

Yet he didn’t. When he reached the restaurant where they’d agreed to meet—late, for in his fluster he’d crossed the street wrongly and been fined—he passed her three times without a spark of recognition. He sought the Naive of his youth, his Franziska, the seventeen-year-old Lisbeth.

And Lisbeth Schlichter, now forty-two, searched for the boy who’d penned her a love letter just last night. That this stout, bald gentleman, standing lost among the tables, might be that boy from twenty-five years past? The thought never crossed her mind.

At last, their eyes met—searching, tentative, then surprised, finally startled. By this shift in their faces, they knew each other.

The lunch that followed was nothing like they’d imagined. The vibrant past, so alive that morning, lay dead before them, and they spoke its eulogy.

After the meal, they sat in silence. “Like mourners grieving a lost one,” the actress said suddenly, a smile breaking through.

Herr Fiebelkorn rubbed his bald head sheepishly, then ventured bravely, “We meant to give each other a gift—now we’ve robbed one another.”

Lisbeth Schlichter regarded him with cheer. “Already so wise?”

“He who’s wise has humor, too.”

“Oh, then not all’s lost, is it?”

“No,” he replied. “Then we’d have a new footing—one suited to our years.”

“Yes,” she said brightly, reaching across the table to clasp his hand.

We Children Congratulate

A radiant glow of festive days bathes the lives of our children. Father’s birthday, Mother’s birthday, Christmas—these are moments of boundless wonder, and how splendid it is when they’re allowed to perform! With tender zeal, they rehearse, and when the great hour arrives, their small hands grip the bouquet tight with joyful thrill.

Yes, these little verses of celebration are woven into the fabric of German family life, a thread of its heartfelt poetry. One thing is essential, though: they must be simple, clear, and childlike in feeling and voice.

Today, we offer a few birthday poems, with more to follow in later pages. May mothers and children find delight in them.

Sommerblumen – Sommerpracht, habe ich dir mitgebracht. Will ein Verschen Dir jetzt sagen mögst du's stets im Herzen tragen: Viel Glück über Glück Vom Himmel ein Stück Vom saftigen Grün Im Sommer blühn. Und alles Schöne — glaub' es mir Das wünsch ich dir!

Summer flowers, summer’s delight,

I’ve brought for you, so bright.

A little verse for you to hear,

Keep it always, hold it dear:

Joy and happiness abound,

A piece of heaven all around,

From the green so lush and true,

Blooming flowers just for you.

And all that’s beautiful and bright,

I wish for you with all my might!

(The children hold a bouquet and wear a small wreath in their hair.)In einem Garten — auf einem Baum Da träumen wir unsern Apfeltraum. Doch plötzlich stört man uns aus der Ruh'. Der Wind, der pfiff uns ganz ärgerlich zu: Wacht auf ihr Faulen, hört auf zu träumen Wollt ihr denn den Geburtstag versäumen! Und eh' wir uns etwas zurecht gerüttelt Hat er uns einfach vom Baume geschüttelt. So ein Windikus — so ein frecher Geselle. Auch ohne ihn wären wir pünktlich zur Stelle. Denn Birnen und Pflaumen und Äpfel so frisch gehören auf jeden Geburtstagstisch. Und so wollen wir denn vor allen Dingen Kräfte Gesundheit und Frohsinn dir bringen.

In a Garden, on a Limb

We dream our apple-dreams so trim.

But whoosh! — the wind, with cheeky blow,

Ruffles branches, scolds below:

"Up, you dawdlers! Time’s a-fleeting —

Birthdays thrive on timely greeting!"

Before we’ve brushed the sleep away,

Down we drop, no choice but obey.

That breeze! That brash, unasked-for guest!

(We’d have come — no need for zest!)

Plums, pears, apples, crisp and bright,

Claim their place in birthday’s light.

So here we are, with gifts to share:

Health, good cheer — and fruits to spare!

(The children present a basket of fruit.)Ein Körbchen voll Trauben und ein Fläschchen Wein Die schickt der Oktober zum Fröhlichsein. Ich komme und will dir gratulieren, du sollst von allem einmal probieren. Viel Freude und Glück und Zufriedenheit Das wünsch' ich von Herzen dir allezeit.

A basket of grapes, a tiny wine cheer,

October sends gifts to bring joy this year!

I've come to say, with a heart that's true,

"Taste life's sweetness—there's plenty for you!"

May happiness dance, good luck take flight,

And contentment glow like soft candlelight.

These wishes I send, both warm and clear—

From my heart to yours, year after year.

(The children may offer a basket of grapes and a bottle of wine.)