Adolf Bartels: National Socialism, Germany's Salvation - Part 3

Original Translation of "Der Nationalsozialismus: Deutschlands Rettung"

Source Documents: German Scan | German Corrected

Part 3:

The DNVP's Relationship with Jewry

Exposing Jewish Control in German Politics

The Struggle for Authentic German Socialism

As for the German People’s Party’s (DDP) stance toward Jewry, Stresemann's name alone reveals its Judaic alignment. The man now borders on absurdity: It is laughable when he claims that “economics alone has never decided a nation’s fate,” insisting instead that “destiny is shaped by devotion to great ideas and ideals.” Presumably, his great idea and ideal is world where every German marries a Jewess—thereby resolving all strife and allowing us to thrive in league with World Jewry.

The relationship of the German National People’s Party (DNVP) to Jewry is not as straightforward as that of the German People’s Party (DVP), entangled as it is through Jewish marital ties. Undoubtedly, committed anti‐Semites persist within DNVP ranks—indeed, former anti‐Semitic Reichstag deputies now sit as part of its parliamentary caucus. Yet a binding link persists between the German Nationals and the Jews: it is the capitalist worldview, from which much of our German nobility, along with the educated and monied classes, have failed to disentangle themselves to this day.

Thus, although these gentlemen are wont to bandy about the terms “Völkisch” and “Christian”, they embody neither. It is equally demonstrable that certain leaders—such as the regrettably still-unpurged Excellency Hergt1—differ little in essence from Wilhelm Marx and Gustav Stresemann and could walk arm in arm with them.

To summarize: Germany groans under a monstrous clique of Marxist and bourgeois parties, partly sworn to Jewry and wholly beholden to its global economic order. Herein lies the root of this fundamentally un-Völkisch and incompetent government. Nothing is more absurd than when this government postures as the German Volksgemeinschaft:2 never have we endured a government so alien to the spirit of the German people.

This indictment applies as much to Reich President Ebert (I stake my credibility on this) as to Reich Chancellor Marx and most of the ruling class, even if they ceaselessly invoke lofty platitudes about “Volksgemeinschaft”. “Cryptocratic Judenherrschaft3” captures the reality, equally valid in foreign affairs and domestic policy.

Yet this Cryptocratic Judaic domination can only thrive under parliamentarism and the contemporary party system. For this reason, we German ethno-nationalists4 stand as their most implacable foes, resolved to liberate the German people from their grip by any means necessary. To be sure, their collapse will arrive inevitably; but when it does, the German people must be prepared to erect institutions that secure their very existence and foster their own healthy development. It is precisely here that the National Socialist movement steps in: Germanic in essence, born of the authentic Volk itself.

I am acutely aware that German socialism—distinct from Jewish Marxism—has always shaped world currents. Even as far back as the 1901 first edition of my work History of German Literature5, on page 650 I observed:

The sound core of all socialist thought—that, in the national interest, the masses must not be unconditionally surrendered to capitalist exploitation, and that every individual possesses the right to a dignified existence and a share in cultural achievements—had gradually proven irrefutable to nearly all educated Germans; and with it, a new spiritual force arose, what might simply be termed ‘social conscience.’6

Discontented elements often turned to Social Democracy, and the impetuous youth flocked to it in droves. They believed no path existed for the free exercise of their energies under Bismarck’s regime, or perhaps more aptly beneath the weight of his towering personality. Yet clearer-minded and resolute men, those truly committed to the nation, recognized that the Social Democratic Party offered no salvation. Beyond its legitimate advocacy for workers, the party championed ruinous internationalist dogmas, propagated a materialistic worldview, and fell ever deeper under the thrall of Capitalist Jewry. The latter—apart from its penchant for corrosive radicalism—exploited the party as a cudgel against societal elements hostile to its interests, while sabotaging any constructive national effort that threatened its dominion.

This prompted a series of attempts to counteract the dominance of Social Democracy among the people while striving to safeguard the sound social principles found in its core. As early as the dawn of the 1870s, a conservative socialism sprouted up, rooted principally in the teachings of the political economist Johannes Karl Rodbertus (1805–1875). Given its primary following among university professors, this movement became known as Socialism of the Lectern.7

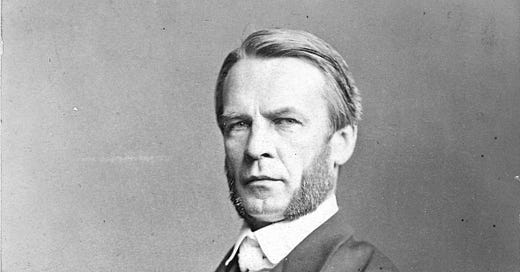

Among the most renowned champions of this academic socialism were the Berlin professors Gustav Schmoller (from Heilbronn, born 1838) and Adolf Wagner (from Erlangen, born 1835). Wagner later shifted toward a Christian-social and staunchly nationalist path. The task of forging a political party for this vision fell to Adolf Stöcker (from Halberstadt, born 1835), Berlin’s orthodox court preacher, whose fierce crusade against liberalism and Judaism made him one of the most reviled figures in all of Germany.

Undoubtedly, Stöcker merits recognition for directing the German clergy’s attention back toward pressing social issues—their natural sphere of concern—thereby putting an end to the habitual indifference that had long pervaded their ranks. This awakening extended even to portions of the Catholic clergy, as exemplified by reformer Franz Hitze.

Great expectations rested on Friedrich Naumann (from Störmthal, born 1860), who in the early 1890s established a boldly National-Social party. Though he attracted considerable support among the educated classes, his efforts—as we now clearly see—ended in utter failure. This failure stemmed from his belief that old-style liberalism could serve as the adhesive between nationalism and socialism coupled with his advocacy of purely democratic and “industrial” ideals and his pursuit of “modernity”. A politics both resolutely national and socially conscious, however, can only take root in conservative soil.

As a writer, Naumann achieved little more than a brilliant flair for feuilleton journalism.8 Equally influential among the educated was the former Old Catholic9 priest Karl Jentsch (from Landshut in Silesia, born 1833), who, in his treatise Neither Communism nor Capitalism10, proclaimed smallholder colonization as society's panacea.

In any case, all these developments undeniably attest that the age of social reform had arrived. While failing to substantially weaken Social Democracy, they succeeded in eradicating the perilous principle of laissez-faire. Moreover, efforts to grant the people a share in cultural life multiplied—exemplified by Alfred Lichtwark's pedagogical treatise Art in the School11 during his Hamburg Kunsthalle directorship, and Ferdinand Avenarius' Masterpieces for the German Home.12

However, it also cannot be denied that these social movements allowed the old sentimental humanitarianism13 to resurface in new guises. Moreover, despite nationalistic posturing, the perennial cosmopolitanism—for the social question is inherently international—reasserted itself. A homogenized European culture of peace emerged, democratic in spirit with aesthetic and educational aspirations. Above all, the Jews found particular delight in this vision.

Oskar Hergt (1869–1967), DNVP chairman 1919–1924, representing continuity with prewar conservatism.

Volksgemeinschaft—literally "people's community"—first appeared in Gottlob A. Tittel’s 1791 translation of John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. It was later refined by thinkers such as F. Schleiermacher, F. von Savigny, and W. Dilthey, and popularized by F. Tönnies in his 1887 work Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft.

Verkappte Judenherrschaft: Rendered with Greek-derived "cryptocratic" to preserve nuance lost in the more literal "disguised." The German is untranslated in the text to highlight the juxtaposition of -schaft terms.

Deutschvölkischen

Geschichte der deutschen Literatur

Sozialgefühl

Kathedersozialismus

Feuilleton writing refers to a style of journalism that is light, entertaining, and often focused on cultural topics, typically found in the cultural sections of newspapers.

The Old Catholic Church is a denomination formed in the 1870s by German-speaking Catholics that split from the Roman Catholic Church in the 19th century over doctrinal differences, particularly regarding papal infallibility.

Weder Kommunismus noch Kapitalismus

Die Kunst in der Schule

Meisterbilder fürs deutsche Haus

Humanitätsduselei - pejorative term