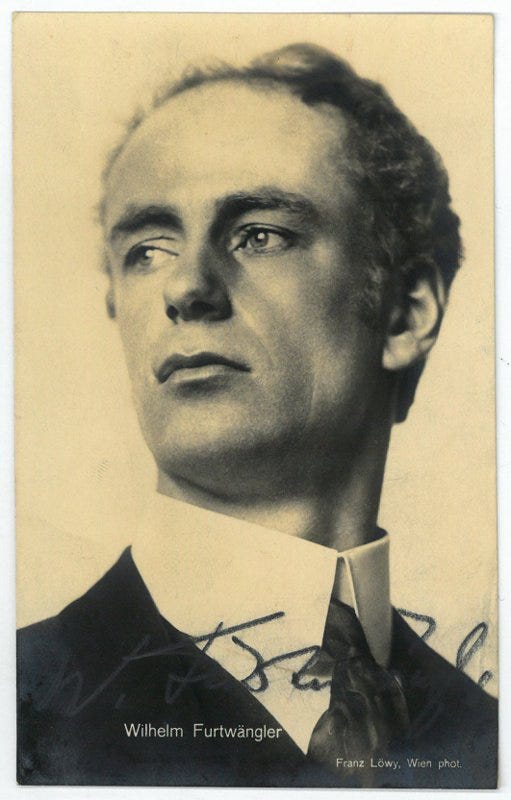

Wilhelm Furtwängler: Conversations About Music

[Der Weg 1948-11] An original translation of "Gespräche über Musik"

Title: Conversations About Music [de: Gespräche über Musik]

Author: Wilhelm Furtwängler

“Der Weg” Issue: Year 02, Issue 11 (November 1948)

Page(s): 765-766

Dan Rouse’s Note(s):

Der Weg - El Sendero is a German and Spanish language magazine published by Dürer-Verlag in Buenos-Aires, Argentina by Germans with connections to the defeated Third Reich.

Der Weg ran monthly issues from 1947 to 1957, with official sanction from Juan Perón’s Government until his overthrow in September 1955.

Source Document(s):

[LINK] Scans of 1948 Der Weg Issues (archive.org)

Conversations About Music

By Wilhelm Furtwängler1

In Bach, every note carries a harmonic and melodic functional meaning simultaneously. Rhythm does not emerge as an independent factor; the whole unfolds without any entanglement or obstruction. Even the slightest hint of momentary weakness is absent, and the calm, steadfast power of the interplay between linear motion and harmonic events represents an optimum of flowing existence, akin to a sustained state woven into the unfolding action (incidentally, this mirrors the ideal of today’s consciously hygienic-minded individual, for whom the seamless, tranquil operation of life’s functions appears as the ultimate desideratum).

With Mozart—to name only the principal stages—such a sustained state no longer exists; here, the action predominates. For Mozart begins to incorporate rhythmic contrasts, which Bach neither knew nor deliberately sought to eliminate. Yet, in Mozart too, the unfolding of the whole proceeds without knots or clusters. He is no longer epic like Bach, nor yet dramatic like Beethoven. He unites both in a unique manner, never again attained after him. What he does, he accomplishes—like a consummate fencer—with the utmost ease and sovereignty; he masters the greatest and most challenging tasks with cosmopolitan elegance and charm, without the faintest trace of strain or uncertainty. He is the ideal of theorists, of conservators. J. Haydn, the true father of the “sonata,” was the first to introduce the whirlwinds of clusters and obstructions into music with the sudden emergence of rhythmic freedom. With him began the problems that later preoccupied Beethoven. Mozart was the more elegant, almost aristocratic figure; Haydn sprang more from the people. Mozart possesses the greater nobility, the greater sweetness; Haydn, the deeper intimacy, the greater exuberance. How could one dare to say that one surpasses the other? In Haydn’s quartets and symphonies, joy in life is captured as if in whole sheaves. His music is youthful—unlike anywhere else, neither before nor after him. I have never understood why Wagner failed to grasp Haydn. The world would be poorer without him.

Thus, Haydn is the first for whom the overarching musical unity, that great treasure of the era, no longer arises as if by itself—as it does in Bach or still in the fortunate Mozart—but must be achieved. With this begins modern music in the truest sense. In Haydn, and even more so in Beethoven, Bach’s “being” and Mozart’s “action” become “becoming.” In Bach, a work still concludes; Haydn and Beethoven bring a work to an end. Thus, the unity of musical logic, musical action, and psychological logic, as well as psychological action, becomes the task of the age.

Nowadays, there are always people who pit Bach against Beethoven, portraying Beethoven as a Romantic, a subjectivist, and thus a corrupter of the natural order—something to be overcome by us. This view stems from a profound misunderstanding, admittedly reinforced by the common presentation of Beethoven’s works. Bach versus Beethoven—it strikes me as if one were to set an oak tree against a lion, or, abstractly speaking, to pit plant-like being against animal-like being.

Only now, with Beethoven, is music enabled to depict what occurs in nature in the form of catastrophe. No less natural, no less organically true than the slowly evolving, the “catastrophe” is yet another expression of nature. Where the character of music had hitherto been epic, it now gradually gains the capacity to become drama. In Greece, too, developmentally, Homer precedes the tragedians. This is no coincidence. The great epic corresponds to a more naive state than drama, which already presupposes the ability to isolate fates and characters. It comes earlier because description is the first mode of encountering reality. Only when this reality is mastered through description can the artist achieve the degree of abstraction necessary to let figures move of their own accord. Only then can he stand in relation to his own creations as if they were no longer dependent on him but lived their own lives, following their own paths of destiny.

In Bach, “tragic” effects are indeed achieved in terms of mood—think only of the Passions. Nevertheless, Bach remains essentially epic: a theme in his work represents an unchanging being and, even as it unfolds, does not change in the sense of experiencing a fate. The decisive shift, which first entered music with Haydn and then fully materialized in Beethoven, is that the theme within the piece—like a Shakespearean character—undergoes a development. In Bach, the entire potential for a piece’s unfolding lies implicitly within the theme itself; he merely does what corresponds to his main theme, even when—as in a fugue—he introduces counter-themes. In the truest sense, he is monothematic. His forms—the fugue, the aria, and so forth—are all presented to us in the same broad stream. Each piece follows its predetermined path with iron consistency. In Beethoven, the path is not prescribed in the same way, though one could hardly say that the degree of inner necessity governing a piece’s progression is lesser than in Bach. But this progression in Beethoven no longer arises from the first theme alone. Beethoven has multiple themes, whose juxtaposition and interpenetration truly give rise to the piece. These various themes experience and unfold through one another. They endure a fate. The piece emerges—no one in music history achieves this with comparable clarity and strength—from parts that often embody the greatest contrasts within themselves, forming a whole.

For a time, no less a figure than Hans Pfitzner engaged in public debate about whether Beethoven’s ideas were not particularly beautiful in themselves, but rather that their development was what mattered. Some, including Pfitzner, rightly argued that intuition must always be the essential element, even in works like Beethoven’s that contain much “labor.” Others—often with an unspoken tendency to minimize intuition’s role because they themselves were intellectual by nature—presented Beethoven as the textbook example of a creator who achieves everything through work. It is true that individual themes of Beethoven’s, such as the opening theme of the Eroica or that of the Fifth Symphony, cannot claim the rank of a grand idea. Yet Beethoven’s uniqueness lies, first, in his ability to create for each theme its own fitting environment, the “climate” appropriate to it; and second—and this is decisive—in his finding for each theme the partner or partners that allow it to unfold to the limits of its possibilities. Beethoven’s surpassing genius, unmatched in this way in music history, lies in his invention of multiple themes from what seems the same source, the same overarching mood, themes of entirely distinct individual character that only become fully themselves through the life that develops between them, forming a new totality that far transcends the world of the single theme. Thus, it is not the genius of individual invention alone that defines Beethoven—though he has much to show in this regard too (and so those who see more “work” in him are not entirely wrong). His intuition reaches further, for in his finest works he succeeds in devising a series of themes that somehow belong together fatefully, almost lawfully, and in their complementarity lend the work the full measure of richness and vitality that its creator imparts. These methods I call “dramatic” in the truest sense. Beethoven’s themes experience one another like the figures of a drama. Within every Beethoven work, indeed within every single movement, a fate unfolds.

The greatest conductor of our time, Wilhelm Furtwängler, in a booklet recently published under this title by Atlantis-Musikbücherei, Zurich, distilled the rich experiences of his work as a conductor and interpreter of the great symphonic and vocal masterpieces. The wealth of ideas, the depth of reflections, and the precision of Furtwängler’s formulations constitute an awe-inspiring contribution to the chapter of “stylistic penetration” in musical masterpieces. Therefore, we reproduce below a section from the third conversation, which, with marvelous clarity, weighs the three greatest musicians of our tradition against one another and, in its vivid formulation, also erects an unforgettable monument to Furtwängler the writer. Furtwängler will conduct ten concerts again at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires in April–May 1949.

When I was in school, we refered to the Berlin Philharmonic as..."The Men". Furtwanger was magnificent.